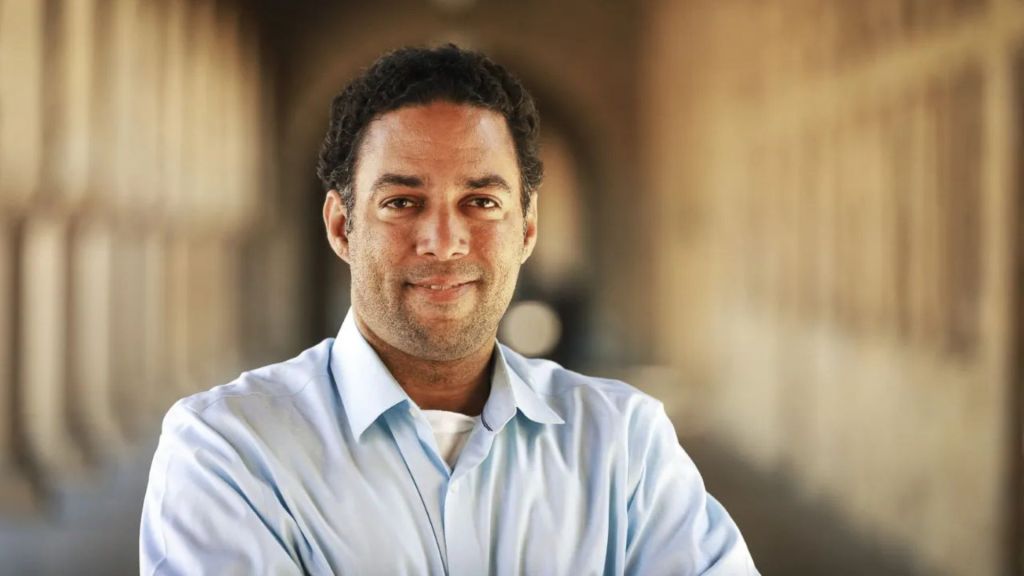

On weekends, Stanford University professor Adam Banks flies from the California campus to Cleveland, on a mission to teach a college-level African American studies class to the Black community — for free.

By Aaron Foley

Every other weekend, give or take, Stanford University professor Dr. Adam Banks boards a jetliner for a four-hour, 40-minute flight from the San Francisco Bay Area to Cleveland, his hometown, to teach Black history and concepts to eager students.

His topics range from the influence of digital technology on the Black experience to Afrofuturism, Black music and literature. His classroom, though, isn’t on the campus of Cleveland State University, Banks’ alma mater; in fact, it isn’t at any of the city’s other 19 colleges and universities.

Banks regularly commutes 5,000 miles, round-trip, to hold what he sometimes calls “digital cyphers” — free, college-level lectures and classes for the Black community – in UnBar, a Black-owned coffee shop. The sole prerequisite: support the cafe by buying an item or two.

The goal, Banks says, is to connect people in the Larchmere neighborhood to one another, and create a communal safe space.

“I hope the primary benefit is just community for its own sake,” says Banks, who teaches African American studies at Stanford. “When we’re scattered in so many directions, and so much of our lives is mediated in the digital space, to be around the table together over time is what I hope is the primary benefit.

“And one of my value propositions, if you will, is you can think together around the same kinds of things that college students and grad students are getting at the different places where I’ve taught — for free.”

Banks has done some form of community conversation outside the classroom for more than 20 years of his teaching career, which includes stops at Syracuse University and the University of Kentucky. In the Bay Area near Stanford, Banks works with a community space in East Palo Alto for a similar version of the free course.

Banks’ gatherings in Cleveland draw folks of all ages, and he routinely brings in special guests either in person, or virtually — which is also how attendees themselves can participate if they can’t come in person.

Coming back to Northeast Ohio, which produced Nobel Prize-winning writer Toni Morrison, legendary Olympic hero Jesse Owens, and Oscar winner Halle Berry, is especially important, Banks says. The slow eradication of “third spaces” — gathering places that aren’t at work or home — for Black people to commiserate, Banks says, is motivation for his mission.

“What a lot of people don’t know is that Cleveland is a majority Black city,” Banks says. “I was real clear that I wanted to do something both for the Bay and for home. I’ve always repped for home, always felt an ambassadorial function there.”

But like so many Midwestern Great Lakes cities, he says, “Cleveland’s vibrant, but Cleveland is poor. We don’t have the resources in my hometown that folks have.”

Teaching Black studies at a time when diversity, equity and inclusion measures are being dismantled at the federal level — and American public education at large could be overhauled — hasn’t deterred Banks from his mission.

“I’m ‘10 toes down’ on what I do and the commitments I bring to it,” he says, acknowledging President Donald Trump’s ongoing attacks. “You can’t write the First Amendment away by executive order. And I believe academic freedom is necessary and crucial.”

Black folks, Black practices, Black traditions, Black truths “are every bit as foundational to this country as any and everybody else’s,” he says. “And so our traditions and practices and truths and understandings deserve inquiry, deserve exploration.”

“We’ve lost so many of the community spaces that we’ve been used to,” Banks says. “We deserve spaces to think together, to affirm each other, to support each other that are big enough for all of us no matter where we come from.”

He goes on: “I don’t care if it’s an assistant principal, somebody who works at one of those barber shops or beauty shops, somebody who just got out from doing a bid, somebody who is in grad school. No matter where we come from, we deserve space where we can think together and be affirmed together.”

How that space is created in ways that are as robust as possible and safe as possible “is my primary goal.”

This article was originally published by Word in Black.

The post Bringing Black studies to Black people appeared first on AFRO American Newspapers.