By Rev. Dorothy S. Boulware

Word In Black

A little more than two years ago, I awoke to an ordinary day. I did the usual morning tasks before starting my day as managing editor of the AFRO: I responded to emails, returned phone calls. Everything was fine, until it wasn’t: I suddenly passed out.

Fortunately, I was at home and wasn’t alone. My husband and my adult daughter were there with me. When I came to, I was just as shocked as my family. The only unusual feeling I’d experienced that day was extreme exhaustion. It didn’t seem serious.

At the University of Maryland Upper Chesapeake Hospital’s emergency department, however, doctors repeatedly asked me about shortness of breath and chest pain. They told me I had a pulmonary embolism — blood clots in both lungs. Then, they drove home how serious it was..

“Usually,” they said, “when we see patients with lungs like yours, they’re already dead.”

Each year, an estimated 100,000 people die from complications from a blood clot, including heart attack or a stroke. An additional 900,000 people who survive blood clots face long-term health complications, including paralysis or brain damage.

Black Americans are particularly at risk: we have up to a 60% higher incidence of blood clots, and mortality from them, than white people. The condition remains a leading cause of Black maternal mortality in this country.

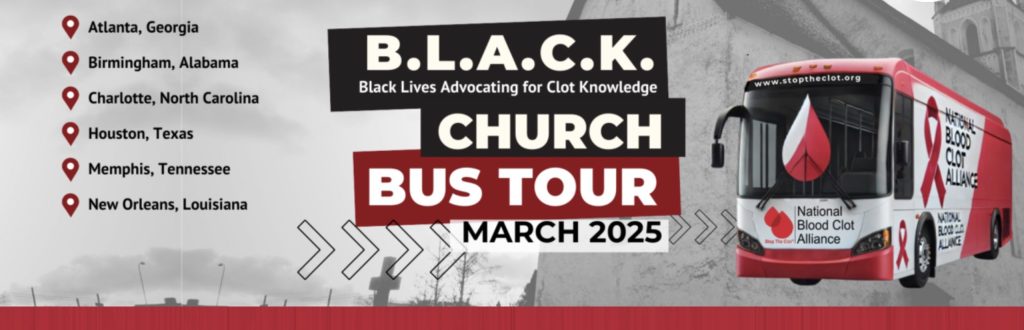

To address this crisis, the National Blood Clot Alliance is launching a six-city bus tour, spreading the gospel of blood clot awareness at churches in the South. Alliance members will teach their host congregations ways to prevent blood clots, how to identify the warning signs and the steps they should take to manage the condition.

“It is well known that Black Americans face significantly higher rates of blood clot incidence and mortality, yet information about blood clots is not reaching our communities,” Arshell Brooks Harris, an NBCA board member, said in a statement announcing the tour. “We are taking awareness directly to the people and providing the information they need to protect themselves and their loved ones.”

According to the American Heart Association, a blood clot, or thrombus, happens when blood flow through the body slows in an area, allowing blood to collect and congeal. The clot builds, then breaks free and moves through the bloodstream until it lodges in a narrow passageway.

The clot, called an embolus, blocks blood flow, starving vital organs, tissue or limbs of oxygen. An embolus in a coronary artery can cause a heart attack; in a cerebral artery, it can cause a stroke.

Each year NBCA serves more than 3 million people with blood clot-related information, resources, and support. Sadly, Harris knows about the subject from experience: her daughter, Leschel Brooks, died from blood clots.

“Nobody should be dying from blood clots, given how preventable they are,” she said.

The bus tour, which will kick off Blood Clot Awareness Month in March, will make stops at churches in Atlanta, Birmingham, Charlotte, Houston, Memphis and New Orleans.

Shirley Bondon, executive director of the Black Clergy Collaborative of Memphis, says the tour is a significant step forward in bringing attention to the issue and potentially saving lives.

“We look forward to partnering with the National Blood Clot Alliance and raising awareness about blood clots in the Black community in Memphis,” she says. ”Knowledge is power, and with information, we can reduce both the incidence and mortality of those impacted by blood clots in the Black community.”

Bondon and others believe the bus tour can be a godsend for everyone, not just church members. The church events are open to residents of surrounding communities, and churches can still register to be hosts for the tour.

As for me, I’m doing much better — doctors believe it was a fluke condition and not a chronic illness. After 6 months of taking blood thinners, I am clot-free. I’m thankful to be alive and glad it hasn’t affected my lifestyle.

Passing out, it seems, was a wake-up call.

For more information about NBCA visit www.stoptheclot.org.

This article was originally published by Word In Black.

The post Blood clot awareness group to tour Southern Black churches appeared first on AFRO American Newspapers.