By Jared D. Childress,

Sacramento Observer

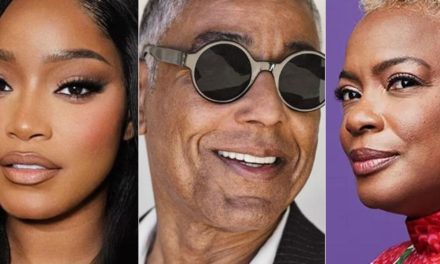

First impressions are everything. At first, Kirsten Johnson didn’t like yoga.

A doctor said it would help mitigate her arthritis and spinal issues, so she dropped into a class at a big box gym in the Rosemont are of Sacramento, Calif. – but it wasn’t what she’d hoped. Instead of feeling better, she left in more pain. The yoga instructor wasn’t very helpful, leaving the then 46-year-old to contort herself into positions not suited for her differently abled body.

That class could have been the end of Johnson’s yoga journey. But, at the insistence of a friend, she went back for a second class. This time, she had a much different experience. With a much different teacher.

“This teacher was what I needed at the time. She came up to everybody and welcomed them. And not only did she say hello but she knew them. That really got me and I stayed in that class,” Johnson said. “And there were more people like me in this class. There were older people, Black people – all types of people.”

That single positive experience in 2012 grew to a regular practice culminating with her completing a 200-hour teacher training, becoming a certified yoga instructor in 2017. Today, the 57-year-old is the president of Yoga Moves Us, a non-profit which offers free community yoga classes in the Sacramento area.

“Community yoga changed my life and I really wanted to give that opportunity to everybody I knew,” Johnson said. “But I know that for Black, brown and marginalized people, yoga is not accessible. It’s expensive… So my mission is to make it accessible, inviting and inclusive for everybody.”

Yoga is a multi-billion dollar global industry estimated at $37.46 billion in 2019, and is projected to reach $66.23 billion by 2027. In the United States alone, it rakes in $9 million annually with the average yogi spending $1,080 a year toward their practice.

More than 36 million Americans practice yoga, but the largest consumers are by-in-large affluent White women. In 2002, 85 percent of yogi’s identified as White and 70 percent were female.

Over the last two decades, Blacks participation in yoga has seen a slight incline. It climbed from 2.5 percent in 2002 to 9.3 percent in 2017, according to National Health Interview Survey data. Additionally, Blacks make up 5.7 percent of yoga instructors.

While it may seem fitting that the face of this lucrative business remains wafer-thin White women bent into pretzel-like shapes on yoga magazines, there’s more to it than phenotype, fitness, and finances.

Yoga means “to become one with” and is derived from the Sanskrit word “to yoke.” And the ancient spiritual practice began in communities of color. Its origins are often traced to northern India 5,000 years ago, but what is lesser known is that it also has roots in Africa.

Sacramento | @in_her_voices

Angie Franklin is a Sacramentan who practices kemetic yoga. This system of yoga was developed in the 1970s and is based on ancient Egyptian yoga postures said to predate Indian origins. Franklin continues this ancient practice as founder and CEO of Afro Yoga, a wellness movement that is revolutionizing the industry.

“There’s a gap in understanding that we actually come from these practices — these practices are in our DNA,” said Franklin, 36. “The marketing we’ve seen and the colonial mindset has co-opted it to the point where the [originators] can actually feel disconnected from the practice that was theirs to begin with, which is wild to think about.”

But Blacks don’t have to look to ancient history to see themselves in yoga. In more recent history, yoga was used by Black leaders as a tool for liberation. Rosa Parks practiced yoga alongside her niece and nephew in the 1960s; the Black Panther Party instituted meditation and mindfulness at the Oakland Community School; and Angela Davis practiced handstands in prison to relieve migraines.

Much like Black history, a lot of yoga’s history is passed on through the oral tradition. But one of the first to put the tenets of yoga in writing was Patanjali, an Indian sage who in 400 C.E. codified the “Eight Limbs of Yoga.”

The 8 Limbs of Yoga are aspects of the ancient discipline that promote spiritual growth. While understanding the sanskrit words can be difficult, they can best be seen in how yogis live their lives on and off the mat.

The OBSERVER visited Black yogis in the Sacramento area to learn how these eight aspects manifest in their daily lives. While some came to yoga on the heels of incarceration, others came by way of a high school class, and some stumbled upon a gym class. All have an individual experience with the daily spiritual practice.

Moore’s Martial Arts of Sacramento | @itsleonwillis

Kirsten Johnson tried to avoid negative self-talk on her recent trip to Southeast Asia. She’d lost her cell phone in a foreign country and didn’t want her thoughts to spiral into worry. So she walked with intention, focusing on her breathing and — at times — leaning on her cane for support. She eventually found her phone and avoided undue stress.

For her, this is yama: choosing nonviolence for her own mind and body, and teaching modifications to make yoga accessible to all.

“If I tried to do some of the poses that other people do, I’d be harming my body — that’s where non-harming comes in,” Johnson said. “I can still find strength in my body and still find strength in the pose, but I just don’t necessarily do it the same way as everybody else.”

Run-ins with law enforcement were a hazard of the job for graffiti artist Leon Willis. Awaiting trial for vandalism in 1996, he made use of his time behind bars by exploring movement, doing what he called “slow breakdancing.” He also kept his mind busy by picking up one of the only books available: the Bible. For the first time he was open to the sacred text.

Yoga came to him in 2006. He’d sustained injuries after being jumped at a house party and his girlfriend thought it’d help with his recovery; his jaw wired shut and with not much else to do, he was open to the experience. Ten years later, he’d be certified in power vinyasa at Yoga Shala in downtown Sacramento.

Today, Willis’ past has made him uniquely qualified to help other people. He’s taught incarcerated people as part of the Prison Yoga Project; he teaches free classes with Yoga Moves Us; he’s created a form of movement called “Alphabetex,” which combines street art with martial arts and yoga; and he’s turned his passion for graffiti into the “POPS” arts education program for youth.

For him, this is niyama: his spiritual foundation manifesting as acts of service to others.

Instructor at Solfire in Downtown Sacramento

“I really enjoy these acts of service; it’s all designed to give back and just be a big brother,” Willis said. “Through this practice I’m bringing self-defense to the yoga world — in a fun, ‘hip hop, you don’t stop’ kind of way.”

The police in 1970 were looking for a young Black man with an afro and Dwight Armstrong fit the description. He was arrested while walking back to his alma mater, Sacramento High School. That false arrest began a decades-long entanglement with the legal system fueled by a nasty drug addiction. But a turning point came in 2012 when then 60-year-old Armstrong chose drug court instead of going back to prison.

Part of his court-supervised program was mandatory yoga class.

He thought yoga was an easy practice he could do in his sleep, but quickly found that the physical practice was demanding — forcing him to be strong in ways he never thought he could.

Ten years later, he’s still a sober yogi. For Armstrong, this is asana: an embodiment of inner strength.

Poteesa Enakaya had been teaching yoga for just two years when in 2013 she got the call that her mother had dementia. The doctor’s words hit her like a ton of bricks; tears welled in her eyes and she began to hyperventilate – bringing the conversation to a standstill.

Her yoga practice was tested at that moment. She breathed through the intense emotions, allowing long exhales to calm her nervous system. She was able to bring herself back to the present, listen to the doctor, and focus on a plan of action.

NYLA in Folsom | @moyogaforyou

Enakaya doesn’t only use breath practice in times of crises, it accompanies her through daily life, breathing periodically to help her refocus or at night to calm her body for a restful sleep.

For Enakaya, this is pranayama: being mindful and breathing through the ebb and flow of life.

“As Black people, we are confronted with a lot of stressful situations,” Enakaya said. “I have come to realize that the way I practice on my mat is the best way for me to live my life when I’m off my mat. When I’m in a challenging situation, I use that same breathing technique to relax my nerves.”

Monique Goldfried wasn’t interested in powerlifting with her husband. Instead, she found herself looking through the glass at the gym’s yoga class. It looked peaceful — but she could also see the rigor.

She could also see that not many people looked like her, but Goldfried wasn’t afraid to buck the trend.

Soon enough, she was in the class finding the sukha, or “sweetness,” in the uncomfortable postures. She wasn’t simply breathing through the malaise, she took it a step further: she was using the time for self-reflection.

For Monique, this is pratyahara: silencing the noise from the outside world and instead looking inside.

Instructor | @EbonyVibesYoga

“I remember my first yoga teacher telling me I’m stronger than what I think. I’ve heard that before, but she was talking about the yoga poses,” Armstrong said. “If I can do it on the mat, then I can extend it to some life things – like staying sober.”

“The difference between a workout and yoga is that yoga is a ‘work in.’ It’s about looking inward and looking inside,” Goldfried said. “The mind is the master manipulator. It can make you think you’re in danger, when you’re really okay. It’s about feeling your heartbeat and saying ‘I’m loved, I’m safe, I’m going to be OK.”

Beads of sweat drop down John Winston’s face but he doesn’t bat them away. Instead, he is laser focused on his reflection as he balances on one leg, lowering his upper body toward the floor.

Winston isn’t a yoga instructor — he’s a 60-year-old diabetic who practices one of the hottest forms of yoga, Hot 26. It’s done in a room heated to 105 °F with 40 percent humidity and was developed by Bikram Choudhury in the 1970s.

Unlike classes where yogis close their eyes and move at their own pace, Hot 26 calls for yogis to keep eyes open and move in tandem with each other. This type of military precision demands unmatched focus and concentration.

For Winston, focus is a non-negotiable that starts long before he walks into the sweat-stained studio. Throughout the day he hydrates and eats well, drinking electrolytes and having a pre-class snack of peanut butter crackers or yogurt. During class, he monitors his glucose levels with the dexcom transmitter stuck to his abdomen.

& Wellness in Elk Grove

For him, this is dharana: being focused on his health on and off the mat.

“When you’re looking in the mirror you start to understand that you are there for you,” Winston said. “Yoga is good for your health — and it’s for everyone.”

It usually takes a while to work up to a solid meditation practice, but for Domynique Herndon it was the foundation of her practice. While a senior at Sacramento High School in 2011, her adviser, Janna, walked in, turned off all the lights, and told the teenage class to close their eyes; they were going to meditate. Herndon was caught off guard — but her curiosity piqued. In her last few months before college, and on her breaks from Xavier University, she accompanied Janna to yoga classes.

She made the decision to take yoga teacher training in 2018. And while at the Solfire training in downtown Sacramento, a question was posed: where would the incoming teachers like to teach? Herndon’s answer was unlike her peers. She didn’t name a studio, rather she spoke of teaching in the community. Herndon’s ambitions were radical; before the COVID-19 pandemic, there weren’t as many independent yoga teachers. She made good on her promise, she taught at the park and led a class at the Robertson Community Center in Del Paso Heights.

For her, this is dhyana: meditation kept her anchored in her vision to take yoga outside of the studio walls and into community spaces.

Yoga Instructor at Functional Elements in Oak Park |

domynique.yogi

“In difficult times or times when I need guidance, you will often find me sitting on my floor, eyes closed, breathing — meditating,” Herndon said. “As a yoga teacher, I start each class in seated meditation … This may be the first opportunity my students have in their day to take a deep belly breath and simply rest.”

Angie Franklin was always a spiritual person. The military brat, who calls Sacramento home, was meditating with gemstones in the fifth grade. But she didn’t immediately hit it off with yoga — she failed her yoga class at American River College in 2007.

Depression and a documentary brought her back to the practice in 2016. She’d moved to Spain and found that racism and lack of community were detrimental to her wellbeing.

Seeking a spiritual solution, she watched the documentary, “Awake,” about the Indian guru Paramahansa Yogananda who in the 1920s came to the West to teach yoga and meditation. This film ignited the yoga within her and she began doing the moves she’d learned in college.

Shortly after, she moved back to Sacramento and experienced samadhi for the first time. During a hot yoga class in Roseville, she held a challenging balancing pose and the words of the teacher resonated with her: release the need to be perfect.

“There’s freedom in accepting yourself as you are instead of trying to obtain the idea of perfection — because the reality is that you already are perfect,” Franklin said. “That feeling of letting go of expectations is a true feeling of ultimate bliss.”

Yoga teacher | @AfroYogaByAngie

She cultivated that feeling, receiving her certification in power vinyasa — but she didn’t stick with the western world’s premier choice of yoga. In 2020, Franklin became certified in Kemetic Yoga, studying with master teacher Yirser Ra Hotep. Today, as founder of Afro Yoga, she teaches Kemetic Yoga and helps others find their own connection to the Divine.

For her, this is Samadhi: a feeling of peace and connection as the result of a daily spiritual practice.

“Sometimes people think that bliss means that there’s nothing wrong, but that’s not what it is,” Franklin said. “It’s that we become more skillful at maintaining our peace. We become more skillful at maintaining the calm in the center of the storm.”

This article was originally published by The Sacramento Observer.

The post Black yogis discuss physical and mental health benefits of engaging in ancient practice appeared first on AFRO American Newspapers .