As part of the leadup to the June 20 game between the St. Louis Cardinals and San Francisco Giants in Birmingham, local historians say it’s essential to remember Black women who also played baseball at Rickwood.

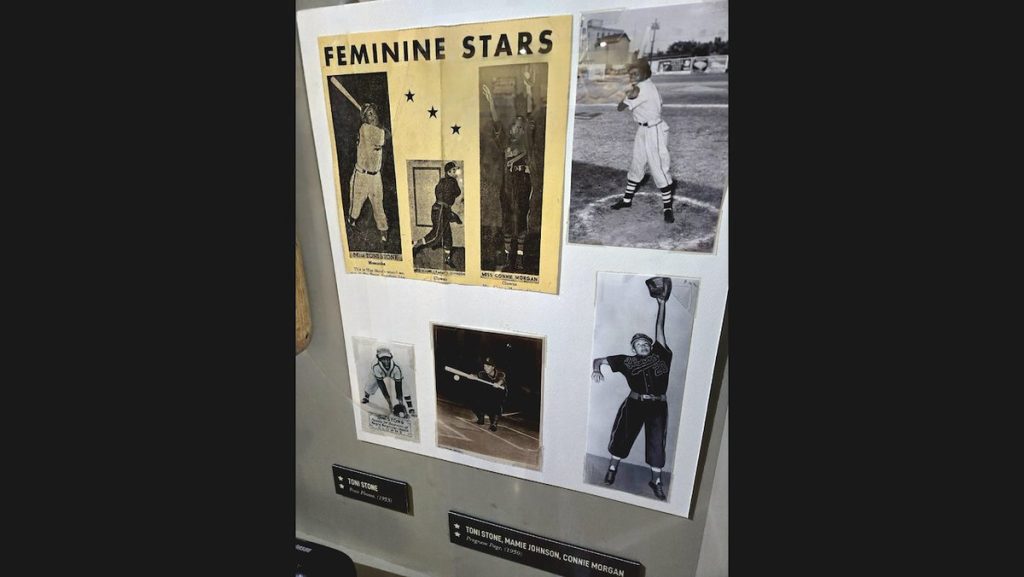

Three women: Toni Stone, Connie Morgan and Mamie Johnson, etched their names in history as the only women to play on all-male teams in the Negro Leagues.

“There’s a whole history out there that’s missing and that has not been talked about,” said Leslie Heaphy, a Negro Leagues and women’s baseball researcher and associate history professor at Kent State University. “There are people’s stories who nobody knows anything about.”

The “MLB at Rickwood Field” coverage has featured the stories of many Black male players. But Heaphy said there’s “a very underdeveloped picture” of the full spectrum of baseball history, Black history and women’s history. Those stories aren’t often told.

“Anytime there’s a group of voices are missing, you’ve got an underdeveloped story about that history,” Heaphy said.

According to Heaphy, women have been playing baseball for almost as long as men, with all-Black women teams dating back to the late 19th century. They persevered despite dealing with sexism and racism, experiencing injuries like their male counterparts and even playing while pregnant.

Diehard baseball fans may recognize the names of these talented players who kept Black baseball going as the major leagues inched toward integration. Both the Negro Leagues and Major League Baseball memorialized them.

But if these names aren’t familiar, here’s some of their history:

Born Marcenia Lyle, Toni Stone, one of the first women to play for a men’s baseball team, was a talented athlete even as a child growing up in Minnesota. She excelled in track and figure skating before she started barnstorming with Black male baseball teams as a teenager.

Stone learned persistence from her parents, who “long preached the importance of personal accomplishment,” as told in her biography, “Curveball.” Her father, Boykin, attended Tuskegee Institute in 1908 and instilled in his children the importance of ingenuity and taking up a trade after learning from Booker T. Washington.

“If people are going to talk, then give them something to talk about,” Stone’s mother, Willa, told her.

Stone played for multiple men’s amateur and barnstorming teams but made a name for herself on the Indianapolis Clowns. Coach Syd Pollock recruited her in 1953 to replace legendary second baseman Hank Aaron when he left for the Milwaukee (Atlanta) Braves.

“She was a very good baseball player,” Aaron said.

Pollock traded her to the Kansas City Monarchs, and she retired in 1954. At one point, Stone’s batting average was .364, one of the top five averages in the league.

Pollock brought in Philadelphia phenom Connie Morgan to replace Stone. She already played five seasons with the all-women’s North Philadelphia Honey Drippers.

The Baltimore Afro-American newspaper chronicled Morgan’s prowess at Birmingham’s Rickwood Field. She gave a “sparkling performance” and wowed 6,000 fans when she began a double play against the Birmingham Black Barons.

“She went far to right to make a sensational stop, flipped to shortstop Bill Holder and started a lightning doubleplay,” the article read. Morgan played one season with a batting average of about .300.

Pollock also recruited pitcher Mamie Johnson in 1954. Johnson was nicknamed “Peanut” because of her small 5-foot-2-inch frame. Morgan attempted to try out in the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League but left when white women stared at her as though she didn’t belong.

“I’m so glad to this day that they turned me down,” Johnson later told The New York Times. “To know that I was good enough to be with these gentlemen made me the proudest lady in the world. Now I can say that I’ve done something that no other woman has ever done.”

Johnson’s experience was reflected in one of the shortest (less than 15 seconds) but most memorable scenes from the 1993 hit movie “A League of Their Own.” A ball is thrown out of play during warmups. A Black woman spectator picks it up, throws a whopper over Dottie’s head (played by Geena Davis) to Ellen Sue (played by Freddie Simpson), who winces a bit from the force of the throw. The resolute Black woman, dressed in her finest, nods slowly to Dottie and walks away.

More recently, a remake of “A League of Their Own” was a television series for one season on Amazon Prime. One of the main characters is Max Chapman, who is turned away from the AAGPBL because she’s Black but eventually realizes her dream of becoming a baseball player by playing with men. Chapman’s story is a detailed, research-based amalgamation of the stories of Stone, Morgan, Johnson and Billie Harris, the “Jackie Robinson of softball.”

Heaphy said tracking down relatives of legends like Stone, Johnson and Morgan is difficult.

Grifters burned Stone, and she once told a journalist, “I don’t want no ad libbing. I want my real thing.”

Heaphy said there may still be a reluctance to put the women’s stories out there, but also emphasized the importance of amplifying their voices.

“Letting them know, ‘Yes, your story is important and we do care,’” Heaphy said. “And that it’s part of a larger picture and helps us develop that picture and get a better sense of what was and is happening.”

Heaphy is looking forward to attending Thursday’s game and is continuing to learn more every day about Black women in baseball. She is working on a book about their lives both on and off the diamond.

“It’s focusing on the participation of Black women in all aspects,” she said.

Heaphy said the book will include present-day Black women making history, including former minor league coach Bianca Smith, Boston Red Sox senior vice president Elaine Weddington Steward and Jacque Coleman, marketing senior vice president with the Washington Nationals.