By Alexis Taylor,

AFRO Managing Editor,

ataylor@afro.com

“My eye soon caught her precious face, but, gracious heavens! That glance of agony may God spare me from ever again enduring! My wife, under the influence of her feelings, jumped aside; I seized hold of her hand while my mind felt unutterable things, and my tongue was only able to say, we shall meet in heaven!

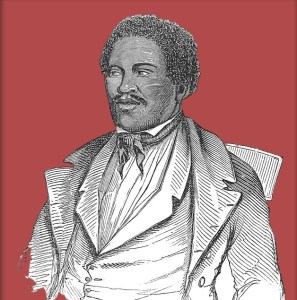

Henry “Box” Brown knew it could lead to a lashing, but it would be worth every drop of blood.

There was no price to be put on the final moments he would ultimately ever spend with his wife, Nancy, and their children, who were sold on the auction block while he worked.

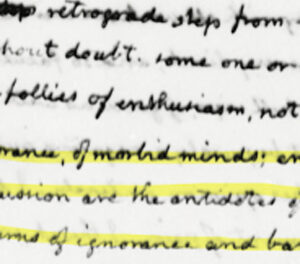

“My agony was now complete, she with whom I had travelled (sic) the journey of life in chains, for the space of twelve years, and the dear little pledges God had given us I could see plainly must now be separated from me for ever, and I must continue, desolate and alone, to drag my chains through the world,” recounts Brown in his autobiography, titled “Narrative of the Life of Henry Box Brown.”

The year was 1848. And in a final act of resistance, a final act of love, Brown did the only thing he could do: he walked side-by-side with his wife, holding her hand as she moved closer to her fate on a North Carolina plantation.

“I went with her for about four miles hand in hand, but both our hearts were so overpowered with feeling that we could say nothing,” recounts Brown. “And when at last we were obliged to part, the look of mutual love which we exchanged was all the token which we could give each other that we should yet meet in heaven.”

Brown would go on to become known around the world as the formerly enslaved man who “mailed himself to freedom.” And while he never laid eyes on his family again, the love of his children and his wife are palpable to this day.

I often wonder why people shy away from the stories that come from the period of chattel slavery in American history.

Is it troubling to read how our ancestors were brutally enslaved and transported during the Atlantic Slave Trade? Absolutely. Is it hard to watch Brown skin split under the crack of a whip on screen? Without a doubt. But woven through the tales of horror are unmatched stories of bravery, perseverance, persistence and yes– even love.

Time and time again we see this repeated throughout history– the courage of love; men and women risking their lives– and even paying the ultimate price– to fulfill the basic human needs of connection and intimacy.

I remember reading this passage more than a decade ago and becoming overwhelmed with emotion. Against the agonizing backdrop of slavery were parents, friends and lovers who had the audacity to form bonds. There were people who eked out happiness even under the grimmest of circumstances and at the threat of having it all disappear in a moment.

The Library of Congress (LOC) went to extensive lengths during the 1930s to record personal accounts of slavery in America from the mouths of the people who survived it. “Slave Narratives: A Folk History of Slavery in the United States From Interviews with Former Slaves” includes beautiful stories that show how love flourished during some of the darkest periods of American and human history.

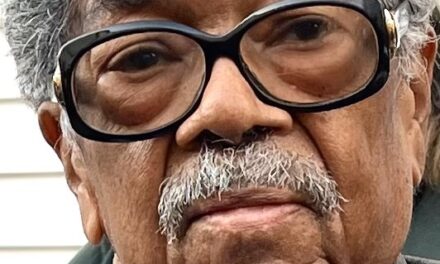

“Hit wus in de little Baptist church at Neuse whar I fust seed big Black Jim Dunn an’ I fell in love wid him den,” reckoned Lucy Ann Dunn, of Raleigh, N.C. “He said dat he loved me den too, but hit wus three Sundays ‘fore he axed ter see me home.”

Dunn was 90 years old when she told her love story on Aug. 4, 1937.

What began as love at first sight bloomed into a courtship.

“We walked dat mile home in front of my mammy an’ I wus so happy dat I aint thought hit a half a mile home. We et cornbread an’ turnips fer dinner an’ hit wus night ‘fore he went home. Mammy wouldn’t let me walk wid him ter de gate I knowed, so I jist sot dar on de porch an’ sez good night,” recalled Dunn. “He come ever’ Sunday fer a year an’ finally he proposed. I had told mammy dat I thought dat I ort ter be allowed ter walk ter de gate wid Jim an’, she said all right iffen she wus settin’ dar on de porch lookin’.”

Dunn detailed her life before and after Yankee soldiers arrived on the plantation she worked with her parents and four siblings. Her love story takes place just two years after gaining her freedom. I often wonder what the ancestors would think of today’s “relationship goals.”

At a time where so many had their relationships controlled, many dared to love who they wanted– an act of defiance punishable by death. I often fear we take so many things for granted– the right to unabashedly love who we want being one of them.

During this month of flowers, chocolates, teddy bears and whispered sweet nothings, I say let’s not forget those who went before us and dared to engage in one of the ultimate protests: the revolutionary act of Black love.

The post Black Resistance: the revolutionary act of Black love appeared first on AFRO American Newspapers .