By Talib Visram

Fast Company

When Robin Pierce Stringer, who is in recovery from drug addiction, had an upcoming court date that would decide if she’d regain custody of her child, she asked her boss if he’d attend court as a character witness. Well aware of Stringer’s situation, her boss upped the offer: He proposed shutting down the entire company for the day and having all 70-plus employees turn up at court as witnesses.

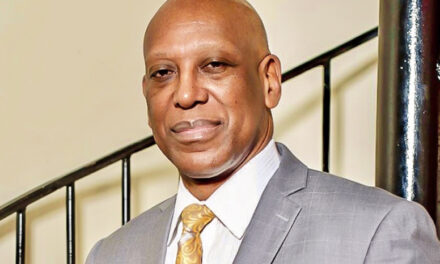

Ultimately, Stringer regained custody without the need for the company shutdown. But that show of solidarity is not an out-of-the-ordinary occurrence at Expedited Transport Agency (ETA), a logistics company in Birmingham, that Tim Cross started in 2011, where the majority of employees are in recovery from alcohol or drugs.

That’s by design, to provide a second chance—and support—for those in active recovery. Many people who have experienced alcohol and/or drug addiction can find it challenging to obtain work due to social stigma, let alone to find a supportive workplace that understands their experience and has resources to allow them to thrive.

Cross, 54, is in recovery from alcohol addiction. As a young boy, he fled home with his mother after his father physically abused her. He says he turned to alcohol as a teen, suffering “drug and alcohol torture” for 20 years before getting sober and rejoining the workforce in the logistics industry. “Somebody gave me a second chance,” he says.

That’s not so common. Addiction comes with stigma, and employers often make judgments about “moral character” (some 9% of the 22 million adults in recovery in the U.S. are unemployed—almost three times the current overall unemployment rate).

When he cofounded ETA, Cross wanted to extend the same opportunity afforded to him to others. The company, which provides trucking and warehousing solutions across industries, transporting goods including steel, tractors, generators, and military equipment, now has 79 employees, about 60% of whom are in recovery, including Cross’s own daughter.

“It is kind of unorthodox,” Cross says. “We decided that the company was not going to be just about us. The company was going to be something that could serve other people.”

Most new employees are hired as so-called sales brokers who contact businesses across the country to secure deals for transporting products. They receive a starting annualized base salary of $32,800, plus commission; after three months, they go entirely on commission. Though he says many workers like the unlimited earning capacity, Cross admits it’s a learning curve and that some do better than others.

Getting Sober

Still, they have the chance to move up the ladder internally. Five out of ETA’s seven managers are in recovery, including the current COO, Crystal Holcomb, who is 10 years sober from heroin use. She was once homeless and on Alabama’s Crime Stoppers list of “wanted criminals,” having turned to robbery to finance her addiction. After she lost custody of her child, she got sober. Cross hired her, and within seven years Holcomb reclaimed custody, got married, had another child, and moved into a brand-new family home.

ETA recruits from various sources, including word of mouth, social media, and job sites. It utilizes Jails to Jobs, a national nonprofit that assists previously incarcerated individuals in finding work (many of ETA’s staff are also formerly incarcerated), and the Second Chance Job Fair held annually in Jefferson County. ETA also recruits from sober living facilities and halfway houses.

As these job fairs and nonprofits illustrate, ETA is far from the only company engaging in “second-chance” hiring. But many recruitment programs focus broadly on those who have been incarcerated. One second-chance organization partners with major corporations such as Lowe’s, Microsoft, and PepsiCo. “There has been a coming-around with employers who are actually willing to give a second chance,” Cross says. “[But] I don’t know too many organizations where 60% of the staff are in recovery.”

For more successful outcomes when employing people who have struggled with addiction, research has shown that companies need a culture of care that starts with adequate awareness and preparation about addiction and recovery. This is what Cross believes sets his company apart; the experience of the workforce allows for a community of “empathy, compassion, and love,” he says. “Those high-profile companies do not have the open-door policy that we have.”

Together We Serve

ETA offers resources as well. Cross started a nonprofit under the company called Together We Serve, and sets aside funding that the employees, who make up the board, then decide how to distribute. Those funds support people financially in their recovery journey. Thanks to those funds and support, one employee, whose fiancé died from a fentanyl overdose, could begin to recover mentally and stay sober through her grieving process.

Though there have been personal success stories within the company, it hasn’t all been smooth sailing. Some employees have relapsed, and one employee died. Cross is adamant about the value of upholding business standards and promoting accountability. “We’re not a fan of enabling people to continue the same behavior over and over again,” he says. “We think it’s just a disservice to the other employees.”

ETA may do random drug testing and has a three-strikes policy for relapses. After two, the employee must seek in-patient treatment and follow a 12-step recovery program; after three, they are usually terminated. Even then, Cross will keep in touch and support them in their personal recovery.

More often than not, Cross says, he sees employees thrive. “It’s kind of a miraculous thing to get to watch unfold,” he says. “There are people getting sober, staying sober, and having a great life.” The experience is also educational for the colleagues on the team who aren’t familiar with addiction. Cross hopes other employers squash the stigma and provide second chances as well. “We want people to know that it’s worth it. The rewarding part far exceeds any difficulties that we’ve had.”