By John Archibald

This is an opinion column.

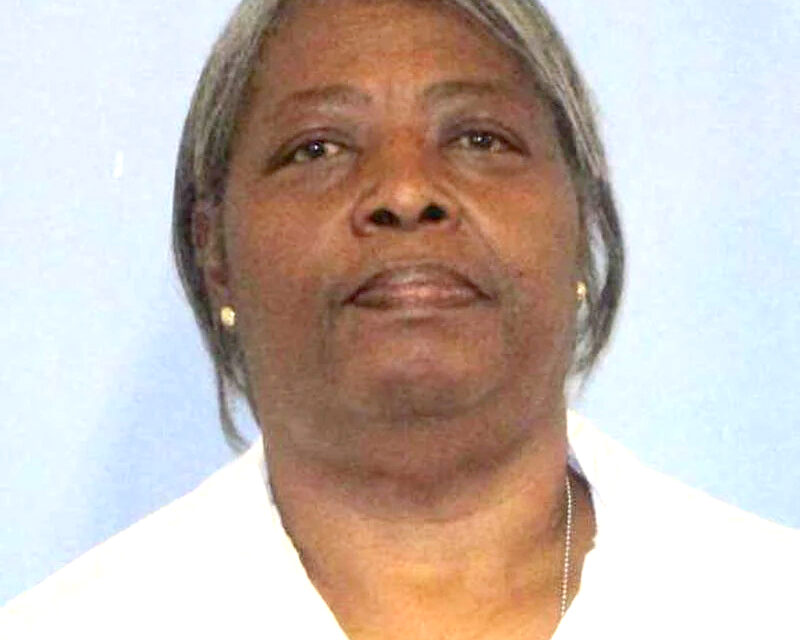

Leola Harris is 71 years old, and has spent more than a quarter of that in Alabama’s Tutwiler Prison. She’s in a wheelchair now, dependent on dialysis, with end stage renal disease and diabetes, among other things.

Harris was convicted of murder two decades ago, for the 2001 killing of a homeless man she knew, Lennell Norris, who came into her house. The circumstances raise questions of their own, and she had no prior criminal history. But nonetheless Harris was tried and convicted, sentenced to 35 years in prison, where she has served 19 without trouble.

Last Tuesday was supposed to be a big day for Harris. She’d been granted a hearing before the Alabama Board of Pardons and Paroles.

Not that she would get to attend that hearing, or even see it on Zoom, because such things are not allowed by this board. They don’t, lest you think otherwise, look anybody seeking release in the eyes.

But Harris did have advocates.

A non-profit called Redemption Earned, led by former Alabama Supreme Court Chief Justice Sue Bell Cobb, sought medical parole for Harris, and spoke for her. Cobb worked to secure nursing home care in the event of her release.

A nurse testified Tuesday that Harris’s health warrants parole. The Department of Corrections gave its blessing, as well, and none of the victim’s family came to speak against her release.

But the parole board vetoed any thought of parole.

After six minutes of consideration – which is all a prisoner gets, and usually less – her parole was denied. Harris will be eligible for reconsideration in five years.

In the event she is alive to see it.

If you think you’re hearing this story because it is unusual, you have it wrong. This is not an anomaly. It is standard operating procedure in Alabama.

This fiscal year, 106 people over the age of 60 have been considered for parole in Alabama, according to parole board records. Just seven – or 6.6 percent – have been granted parole.

This fiscal year, 21 people over the age of 70 have come up for parole. None were granted release. None.

Age, nor length of time behind bars, has not been such a compelling argument for this parole board. But then, few arguments are.

In fact, it is harder and harder to get out of Alabama’s prisons, even with the state’s notorious prison overcrowding, with its federal reprimand as an unsafe, inhumane, unconstitutional torture trap that puts inmates in danger of assault, sexual abuse and death.

The parole board is not just unmoved. It is immovable.

In all the board heard 44 cases Tuesday, including that of Harris. It granted parole to one person. The previous Wednesday was about the same. It held hearings for 45 people, and granted parole to two.

Since 2017, when the board granted paroles in a little more than half of its hearings, the rate of release has dropped every year. It let out 10 percent of eligible parolees last year. So far this fiscal year, which began in September, that number is down to 9 percent.

Even though, according to board records, its own administrative staff recommended granting parole in more than 80 percent of those cases. Even though the board’s decisions, according to those records, did not match the recommendations of parole guidelines 74 percent of the time.

In the end this board, led by former prosecutor Leigh Gwathney, can ignore all the regulations and recommendations it wants. It has the power of discretion, and wields it like a headmistress in a Roald Dahl boarding school.

For Ms. Harris, it is a death sentence, Cobb said.

“Any reasonable person would conclude that 19 years is a sufficient sentence for a 71-year-old woman who is dying in prison,” the former chief justice said in a statement. “No one would say that a dying woman, who is confined to a wheelchair, who cannot perform basic personal body functions unassisted, is a danger to the public. This Parole Board not only failed Ms. Leola Harris, but they also failed the taxpayers of the State of Alabama. This denial of medical parole to a wheelchair-bound, weak, and dying woman is an injustice that the people of Alabama ought not accept or be forced to pay for.”

It’s like they want to show they are tough so badly that they hurt us all.

But it is the time, or lack of it, that gets me most. That and the lack of real consideration, or humanity.

Prisoners, as I said, can’t attend the hearings, but if they have advocates, two are allowed to speak for two minutes each. If they have a lawyer, that can stretch to six minutes.

Six minutes to make a case for life, and freedom, and maybe death. It would take longer to listen to Free Bird.

It’s pretty clear what Alabama wants to hear. And who it doesn’t.