Come with me. I want to show you what a hole in Alabama history looks like.

Downtown Eufaula is postcard pretty. It fits the Hollywood idea of what a small Southern town is supposed to look like, so much so that the producers of that “Sweet Home Alabama” movie took some footage here years ago, although they shot the scenes with Reese Witherspoon across the river, in Georgia.

According to the Alabama Department of Transportation, this road is the busiest state highway in Alabama, and if you close your eyes, you might mistake its sounds and smells for a big city rather than a quaint river town. This is how impatient beachgoers get from Atlanta to Panama City, and where semis and log trucks belch diesel fumes as they rumble in both directions. But turn your head, look out the passenger side window, and you can see the same 15-second clip Hollywood came here for 20 years ago.

On either side of Eufaula Avenue are rows of antebellum mansions that have their own names, imparted by owners who are long since dead. The director of the state tourism department once said the houses looked like wedding cakes. Most, but not all, are in excellent shape, restored by new owners who are as much curators as they are residents.

Lines of old oak trees form a natural canopy over the road. The residents are protective of these trees, many of which memorialize deceased townspeople with small granite markers laid like gravestones among their roots. One tree owns itself, or so a little plaque there says, and there’s even a tiny fence to keep us off its lawn.

Eufaula sells its history to tourists, or at least, a version of it. Each spring, the city hosts the Eufaula Pilgrimage, an antebellum festival when many of these private homes open for tours. Young women dress in hoop skirts and old men button up waistcoats. Typically, about 1,500 people visit from across the southeast. And it’s an event the state subsidizes. Last year, Alabama distributed $247,500 to preservation groups here.

“Experience Southern hospitality at its finest when you visit Eufaula, Alabama,” a promotional video by the Eufaula Heritage Association promises. “During its annual pilgrimage, beautiful historic homes built in the days when cotton was king will be open to visitors during this nostalgic return to the Old South.”

Today we’re going back to an old South, but not that one.

Past the mansions, where Eufaula Avenue meets Broad Street, is the obligatory Confederate monument. In fact, there are lots of monuments and markers on Broad, between the Confederate hospital at one end and the spot where the town surrendered to Union troops at the other. There’s a WWI doughboy statue, a WWII monument, and a waist-high granite memorial to Leroy Brown who was, as it turns out, a fish.

In 1973, the legendary bass swallowed a strawberry jelly worm in Lake Eufaula and thereafter lived in a bait shop live tank until his death in 1980. More than 800 folks attended Leroy’s funeral, and the governor declared an official day of mourning.

Yes, there is history in Eufaula. But there’s something missing.

The most significant memorial in Eufaula is the one that isn’t here. Just a little further down Eufaula Avenue — past that Confederate monument and around the corner from the fish — is the site of a tragedy.

Where today the air reeks with car exhaust, there was gunsmoke.

Where traffic creeps between stoplights, bodies lined the street.

In the median of that busy road was once a massacre.

Here is where Alabama took a bloody turn, something so shocking at the time that it led to two Congressional investigations. It might be the most consequential thing that ever happened in this town.

But you won’t find mention of it — not here, not now.

Step into my time machine. There’s something important I want to show you.

An ambush in 1874

Henry Frazer was a Black Republican when that wasn’t an unusual thing in Alabama. That day he told the men not to bring weapons, he would later tell investigators in one of two Congressional inquiries into what happened that day in Eufaula.

The year was 1874, and Alabama was nearing the abrupt end of Reconstruction. Frazer, who was also a Methodist minister, had spent two weeks canvassing support among the sharecroppers around Eufaula, back when cotton farmers still loaded their crops onto boats. The Monday before Election Day, he led about 400 Black men toward town to vote. They camped by the roadside outside of town, and set off on foot at eight o’clock the next morning, marching to drums and fifes.

“I told them that although they might carry sticks, they should not carry any other weapons,” Frazer told investigators “I instructed them to stand in a body until they got a chance to vote.”

When they arrived in Eufaula, they met another group of Black men coming into town from the other direction. A policeman searched them and as the men began to vote, a man named Harrison Hart rode up on a horse. He asked what time it was.

“Somebody made answer to him that it was nearly twelve o’clock, and he said, ‘In about an hour’s time, we will have a frolic,’” Frazer testified.

Hart wasn’t the only one anticipating a frolic.

The city judge and election supervisor, Elias Keils, had warned federal authorities that trouble was imminent. The night before the election, Keils met the Black voters in rallies outside of town and implored them to endure any insults they would hear and to not return any curses. They were to vote and get out as swiftly as possible.

If they did, Keils said, they would be protected. It was a promise he never should have made.

Nine years into Reconstruction, there were signs already that federal forces had grown weary of their mission reconfiguring social order in the South. At least twice ahead of that election, Keils wrote the U.S. Marshal in Montgomery to ask for support.

“Every day the most vicious of the ‘White League’ are carrying into various portions of this county new breech-loading double-barrelled shot-guns with fixed ammunition, plenty of which has lately been shipped here,” Keils wrote a month before the election. “We all know what this means, particularly when the most infamous threats are daily made by those of the ‘White League’ who control it.”

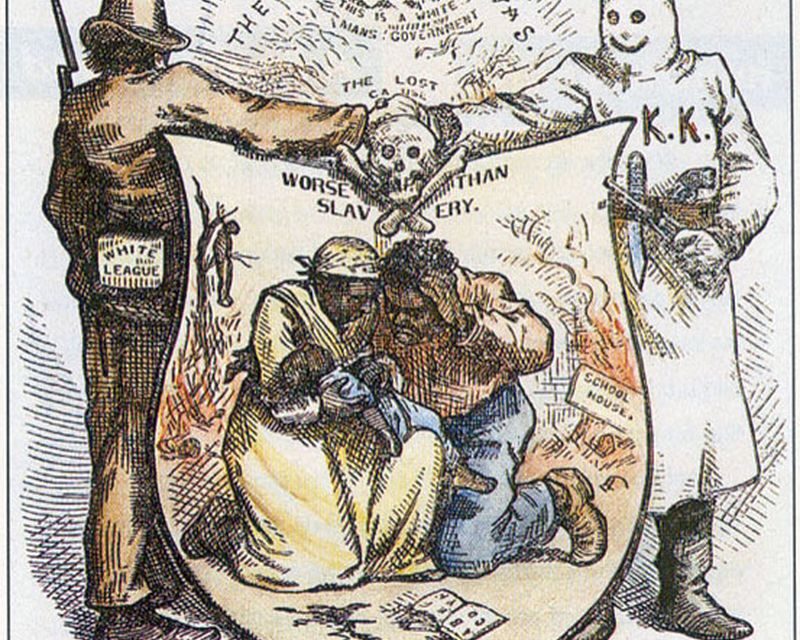

The White League had recently taken root in Louisiana and Mississippi, and its influence was spreading across the South. While it shared many of the same goals as the Ku Klux Klan, the White League operated openly. It had organized militias for driving Republicans and unionist forces out of the South. After the Battle of Liberty Place in New Orleans, the League occupied that city for three days. And it had plans for the 1874 midterm elections.

Keils had been a secessionist before the Civil War but since the war ended he had switched to the Republican Party. He’d fallen out of favor among Eufaula whites, both for his new political allegiance and for the mercy he showed to Black defendants in his court. His opponent in the 1874 election wrote a song about him, which I won’t quote because it uses the n-word a lot, but it makes clear why Keils had fallen out of favor: He protected Black voters, he let one Black defendant work as a doorman in his court, and, the thing they couldn’t forgive, he let Black people serve on juries in judgment of white defendants.

He was, to use the epithet of the time, a scalawag.

James Williford knew what that was like. A deputy U.S. Marshal — Williford had grown up across the river in Georgia. But since he’d joined the Marshals service, he’d become an outsider.

“If a man does anything for the United States Government he is looked upon with about as favorable eyes as Gabriel looked upon the devil in Paradise,” Williford testified later.

But some locals were more cordial than others. That morning, the marshal sat on a box by a storefront, talking about mining with Eli Shorter. Shorter was a prominent citizen in Eufaula, formerly a colonel in the Confederate Army and a Congressman before the war.

Then the frolic started.

According to Williford, Shorter saw the disturbance first and suggested he do something to stop it. Williford wasn’t sure he had the authority, but Shorter assured him his presence alone would settle things.

Frazer, the minister and Republican canvasser, was closer to the ruckus and saw more of what happened.

According to Frazer and other witnesses, there was a dispute about whether one young Black man was old enough to vote. When the man tried to vote the Republican ticket, the officials there objected and some white Democrats took the young man around the corner into an alley. A short while later, they reemerged, but now the young Black man was holding a Democratic ticket and taking it toward the ballot box.

A Black man named Milas Lawrence said to the young man, “God damn you, are you going to vote the Democratic ticket?”

A white Democrat named Charlie Goodwin confronted Lawrence, and the two began to shout at each other.

“I have a right to stand up for my color as much as you have for yours,” Lawrence said.

Still making his way toward the fight, the marshal Williford first reached the young Black man, who by then had voted. Wiliford asked the young man if he had voted as he pleased. When the man said he had, Williford told him to go about his business and that he’d be protected.

“Boys, all you go back to the polls now and vote, and then turn right round and go home,” Williford told them. “This looks like too much a fuss.”

About then the argument escalated. A white man named Clayton yelled, “Shoot the damn son of a bitch!” And then another white man named Dowdy pulled a Bowie knife and stabbed Lawrence in the back. Lawrence tried to flee but fell a few yards from where he’d been stabbed.

That’s when, according to multiple witnesses, Goodwin drew his pistol and fired it straight up in the air. Several witnesses would later say they believed the shot to have been a signal.

The marshal couldn’t see who fired the shot, but he heard a white man shout what sounded like orders. Partially deaf, Williford grabbed the arm of a Black man next to him and asked what was said.

“Didn’t you hear them say?” the man answered. “Fall in, Company A! Fall in, Company B!”

Swiftly, all but a handful of white men shuffled out of the crowd and gathered on the side of the street opposite the polling boxes. The men on the ground drew pistols and shotguns. The second-story windows of the storefronts flew open and from there men aimed rifles at the crowd. The rifles had come from an armory — provided for the town’s protection by the United States government.

Somewhere between 800 and a thousand Black men stood exposed in the street.

Then the shooting started.

This is where witness testimony diverges wildly, and perhaps that’s understandable. Most witnesses said the shooting lasted but for a minute or two, others said nearly half an hour. But all agreed hundreds of shots were fired.

The Black crowd split and fled in opposite directions down the street, and each way about a dozen or more white gunmen chased after them, firing as they went.

One Black man, S.N.B. Johnson, was hit five times before he jumped down a well in the middle of the street for protection.

Frazer fled but quickly hid behind some steps on the side of a house. From there, he could see Harrison Hart, the man who’d warned of the “frolic,” firing at the fleeing men.

Among a larger crowd of white men still standing near the polling boxes, there were cheers. A few men tossed their hats into the air.

“Now, God damn you, bring on your Yankees!” Frazer and other witnesses heard one man yell. “We are ready for them!”

Meanwhile, the marshal, Williford, was trying to get the Yankees.

Like the Black voters, he ran for cover. He later told investigators he could hear the bullets whistle around him. Briefly, he sheltered in a home around the corner. Then he ran to the office of U.S. Army Captain A.S. Daggett.

Daggett’s office was close enough to the poll boxes that he’d witnessed most of the shooting out his window. Williford begged Daggett to stop the ambush.

Daggett refused. Instead, he showed Williford a telegram with orders from Montgomery. It said the federal troops could only help U.S. Marshals serve writs.

“Very well — I have writs!” Williford said. He pulled subpoenas from his pockets and asked for soldiers to help serve them. “I have 15 or 20 subpoenas. Are they not writs?”

“I think not, but I will look in my dictionary to see,” Daggett said before fetching the book.

Daggett suggested Willford leave the subpoenas with him and the soldiers would serve them in the morning.

Williford pleaded some more. The mob outside would kill every Black man if they didn’t do something, Williford argued, but Daggett closed his dictionary.

“I cannot help it if they do,” Daggett said according to Williford’s testimony.

The Yankees weren’t coming to the rescue.

Williford left Daggett’s office and returned to the scene of the shooting. He tried to count the dead but had trouble sorting them from the injured, some of whom were already being carted off on wagons.

The casualty counts vary, but most say between seven and ten men died on the street. Others were found later, dead in the woods outside town, after the buzzards found them first.

Around 80 were wounded — most of them Black, but not all. About five white men had been hit. Henry Shorter, brother of Eli, had been standing on the wrong side of the street and caught a bullet in his wrist.

But the violence wasn’t finished.

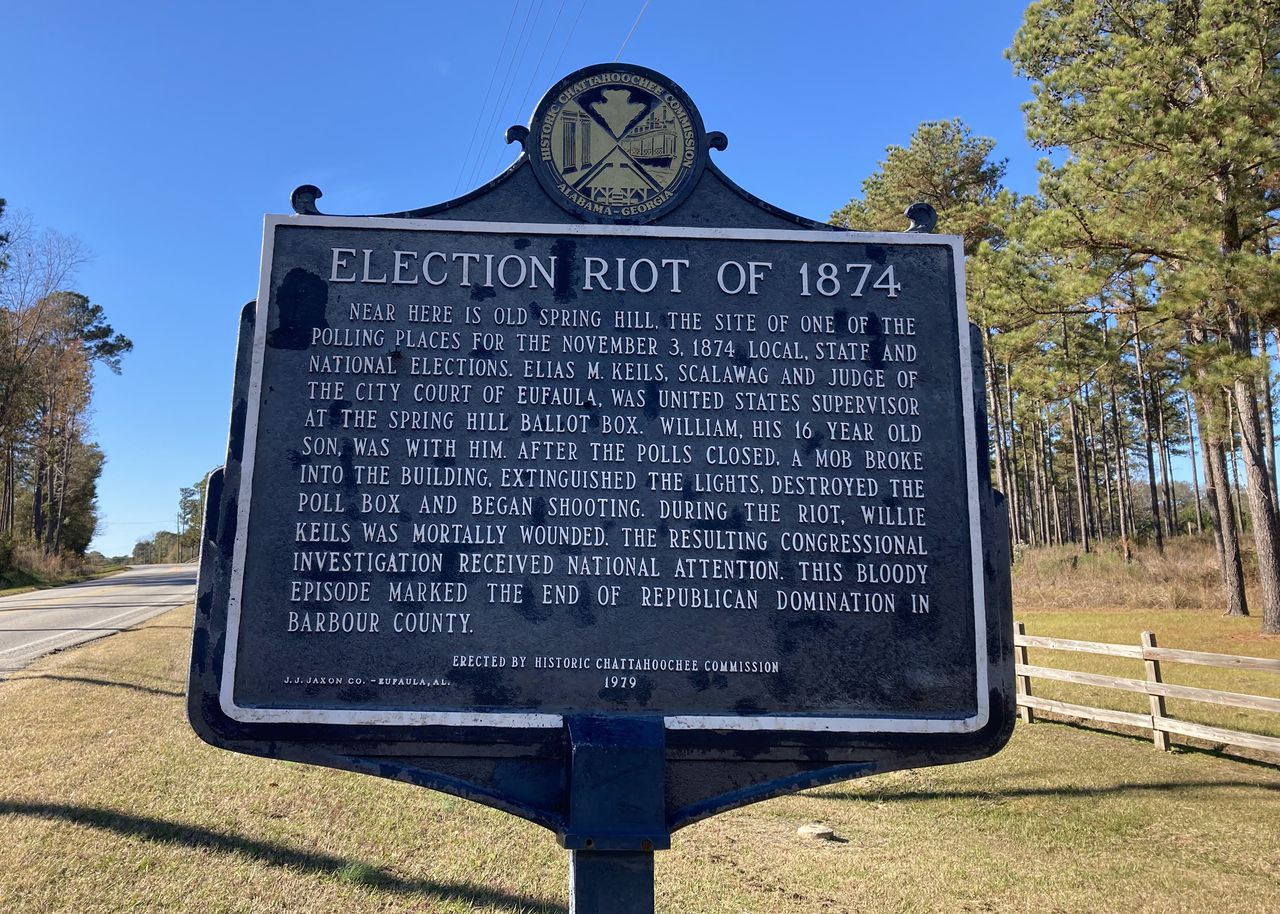

That evening, at another polling place in the nearby town of Spring Hill, many from the same mob surrounded an office where Keils — the judge and election supervisor who’d sent for help — and others were counting votes.

Keils had asked the Union soldiers in Spring Hill for support, too. They showed him a telegram from Daggett — the first telegram ever received in Spring Hill’s new telegraph station — relaying orders from Montgomery not to interfere.

The mob demanded that the judge surrender the ballot box.

When he refused, they shot up the office and burned the precinct ballots. Keils lived, but in the firefight, his 16-year-old son was struck four times and died two days later.

The white Democrats declared themselves the victors and forced — in some instances literally forced — Republicans from their offices. The 1874 election gave Democrats control of the Alabama Legislature and state executive offices. Though the character of the party would change, it wouldn’t lose its majorities in the Alabama Statehouse for the next 136 years.

Federal authorities tried to hold the Eufaula mobs accountable. Williford, the marshal, testified that he arrested about 30 men. A federal grand jury called witnesses. After the first witness, a Black man named Hilliard Miles, testified, he was almost immediately arrested by local law enforcement and charged by a state grand jury with perjury.

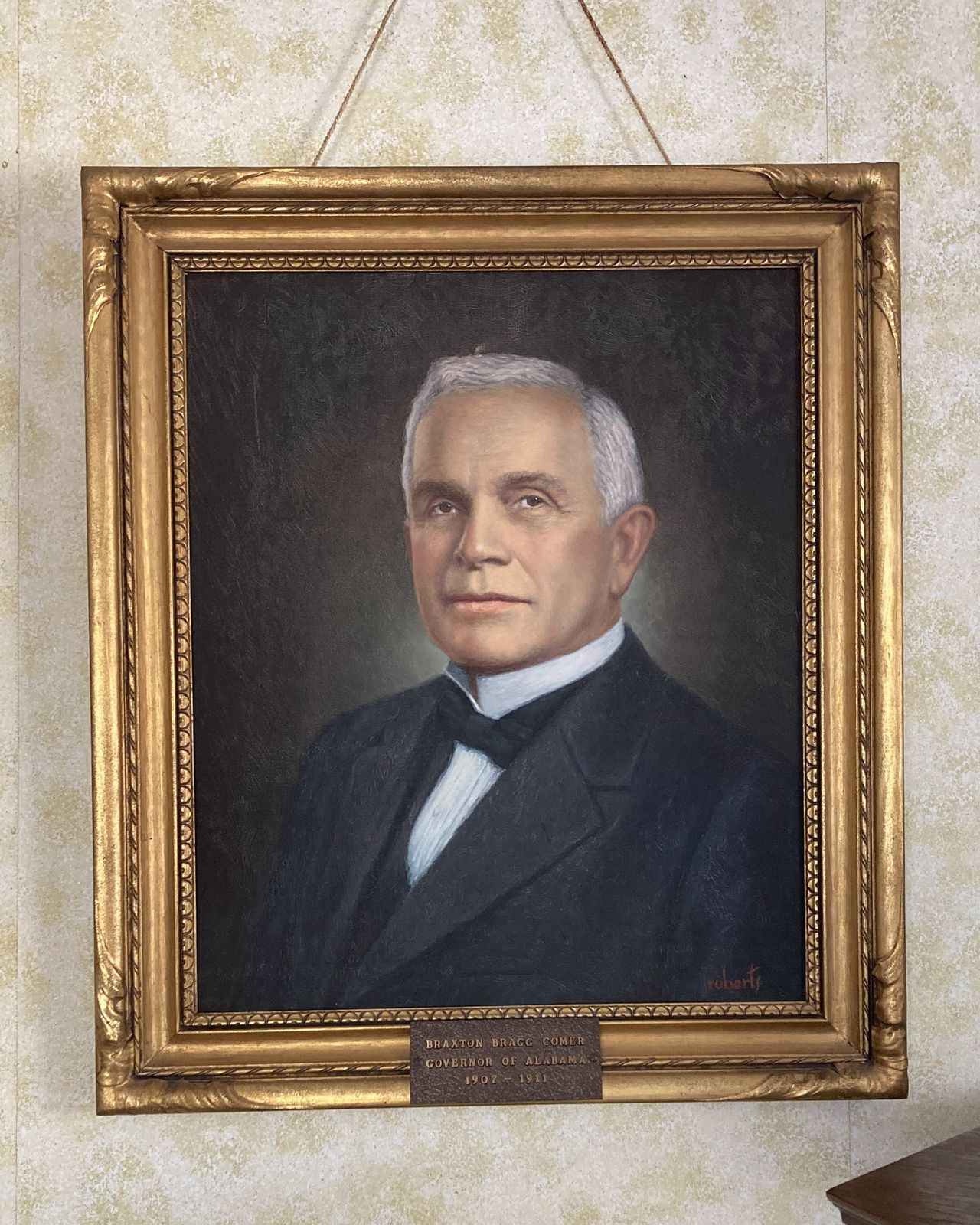

His crime: Naming one of the men he saw leading the White League militia — Braxton Bragg Comer.

That first witness was convicted and sentenced to state prison where federal authorities lost track of him. Witnesses of the massacre stopped coming forward. None of the 30 men Williford arrested were convicted.

The Republican officials and their canvassers, including Frazer, had to flee the county. For his own safety, Williford was reassigned to Texas. Those who had helped the Republicans were blacklisted by employers, or worse.

The previous February, about 1,200 Black voters had cast ballots in Eufaula city elections.

In 1876 — two years after white Democrats took control of the county — only 10 Black voters cast ballots in Eufaula.

Later, Henry King, another of the Republican canvassers, testified to the Congressional committee that no Black men were allowed to vote in Barbour County anymore A congressman asked what would become of them if they did.

“They will come up missing,” King said.

What’s there today?

Five men died in the Boston Massacre and it’s in every American history textbook. About twice as many died that day in Eufaula and Alabama history textbooks neglect any mention of it.

Eufaula has buried it, too.

I grew up in Alabama. In school, I had two years of what I was told was Alabama history. I never heard of any of this. Last year, around the anniversary of the Tulsa Black Wall Street Massacre, I saw a map of similar mass murders around the country.

And there was Eufaula.

Unlike the Black Wall Street Massacre, Eufaula’s secret history wasn’t kept alive only by word of mouth. There were two congressional investigations that produced official reports and included hundreds of pages of sworn testimony from witnesses on all sides. (I’ve now read all of it, which I used to build the narrative above.)

I drove to Eufaula, just to make sure there wasn’t something there to mark the spot. As I suspected, I found nary a thing.

The well where S.N.B. Johnson took shelter is long gone. There’s a fire hydrant in the highway median there now. The buildings the shooters fired from are gone, too, burned in a pair of blazes around the turn of the 20th century. On one end of the block is a Walgreens. At the other end is a tanning salon called Lasting Impressions.

Between 70 and 80 people got shot here for trying to vote. And there’s nothing here to say a thing about them. Around the corner, there’s a memorial to a fish, but nothing for what happened here. Not a monument. Not a marker.

Nothing.

Of the people who died that day, I found the name of only one — Willie Keils, son of the city judge, buried in a neglected corner of the town cemetery.

The Black voters murdered in the street— their names are lost.

About 20 miles northwest of Eufaula, there’s a roadside marker memorializing the attack in Spring Hill that killed Keils’ son, put there in 1979. It doesn’t mention the massacre earlier that day.

“This bloody episode marked the end of Republican domination in Barbour County,” it says.

Also, it refers to Keils as a “scalawag.”

Post-reconstruction

Had not Dr. Richard Bailey told me where to look for the marker, I might have zipped past it on my way to Eufaula. Bailey is a historian and author of “Neither Carpetbaggers nor Scalawags,” an account of Black Republican officeholders during Reconstruction. He lives in Montgomery where he guides tours of that city’s buried history. As he puts it, not everybody cried when Union troops marched up Dexter Avenue toward the capitol.

“Reconstruction is essentially — until recently, at least — an overlooked period in Alabama history,” he says. “Nobody really wants to talk about Reconstruction. We’ve begun to talk about it, but at the same time we are sanitizing it, also.”

Reconstruction, Bailey says, was America’s first attempt at a civil rights movement — when Black people first had full rights of citizenship and some degree of protection from white people hostile to them. When it ended, those reforms died with it, and it began a violent period in Alabama history — a period deliberately covered up.

It’s impossible to know what might have happened in some alternate universe, where the Eufaula Election Massacre never occurred. But we can see what happened in this one, and it’s possible to draw a line from this mass murder, not only to the end of Reconstruction in Barbour County, but to the end of Reconstruction in the South.

The election of 1874 gave Democrats control of state government again, and it gave national Democrats their first post-war majority in U.S. Congress. When the presidential election of 1876 ended in a virtual tie, Democrats had the political leverage to negotiate a compromise — withdraw union troops from the South and the Republicans could keep the presidency.

It also gave Barbour County outsized influence on Alabama politics, Bailey says.

“All you need to do is to pick up a list of Alabama governors and look at which counties they are from,” he says.

Or, you can find them upstairs, in one of those wedding cake houses in Eufaula.

Home of Governors

The Shorter Mansion, built by Eli Shorter II, today is the headquarters of the Eufaula Heritage Association. For the most part, the first-floor rooms are used as event spaces for parties and weddings. Upstairs is where the artifacts are kept, including Confederate currency, a few battle flags, period dresses, but nothing to speak of the slavery this city was built on.

There is, however, the Governor’s Parlor.

In the 1960s Barbour County marketed itself as the “Home of Governors.” Five were from here, although the county has sometimes claimed Lurleen Wallace, a Tuscaloosa native, as a sixth. Her portrait is the largest in the parlor, above a display case of Wallace political memorabilia.

It’s one of six portraits, including her husband’s.

Among them is Gov. Braxton Bragg Comer — the man Hilliard Miles named as the White League militia leader that day in 1874.

He later became a U.S. Senator, too.

Comer succeeded Gov. William Jelks, another Barbour County man. There’s nothing I found to tie Jelks to the massacre although he was generally supportive of lynchings and pardoned members of one whole mob that had been convicted of murder.

As president of the state Senate and as governor, Jelks successfully shepherded the ratification of the Alabama Constitution of 1901, a racist foundational document of Alabama government that disenfranchised Black voters and today centralizes power in Montgomery and away from minority-controlled local governments. The framers of Alabama’s constitution were explicit in its purpose — embedding “white supremacy by law” (their words) in state government.

Comer was the first governor to take office under the new document.

Those murders on Eufaula Avenue helped set all that in motion.

This is the hole in our history.

Reconstruction was America’s first experiment at nation-building, and it failed for many of the same reasons, and in the same ways, as later attempts elsewhere in the world.

While the Republican occupiers did their best to make the South into a more just and equitable place, they couldn’t overcome the subversive resistance of the men they’d ostensibly defeated. Over time, the conquered Confederates wore the Yankees down. Just as Daggett and his federal soldiers refused to help that day in Eufaula, Union forces gave up — and they abandoned new Black citizens when they needed protection the most. When they were gone, the Confederates regressed to their old ways, swiftly and violently.

Deep in the U.S. Senate report on Alabama’s political unrest are a handful of local newspaper clips, evidence of the great reversion happening here through 1877. Those clips show, perhaps in the clearest terms, how Alabama’s white establishment and the so-called Redeemer government perceived the after-effects of the Civil War and they show where the state was headed next. One editorial all but calls for a race war.

“Emancipation threw the whites and blacks on their own resources, and each race must depend upon its own inherent strength. Freeing the slaves was a declaration of war between the Caucasian and African — a war that is going on now and that will go on silently, ruthlessly, and unceasingly until one or the other is exterminated.

“Let us recognize facts — admit that a war of races is progressing — and then every man will range himself under the banner of his kindred. For ourselves we say, No compromise — no ‘unification’ — but a white man’s rule, a white man’s civilization, and a white man’s government, or ruin and extermination!”

It was in that era of violent backsliding — of unreconstruction — when men like Jelks and Comer reshaped Alabama government with a foundational document Alabama still operates under today.

It was in that time that children of Confederates built monuments and mythology — not history, but an elaborate deception.

And one still sustained today with taxpayer money.

Backwards no more

When I returned from Eufaula, I reached out to Doug Purcell, a retired historic preservationist who, until a few years ago, led the Historic Chattahoochee Commission. I asked him why there’s no monument for the massacre. His short answer: No one has asked for it, likely because no one there remembers it.

“Probably 99.9 percent of the people living in Eufaula have no — recollection is the wrong word because they weren’t here at that time — but they just don’t know it,” Purcell says. “They don’t know about the lynchings that took place here in Eufaula. They don’t have any idea when the Confederate monument was erected and how it relates back to the 1901 constitution and Jim Crow law.”

Until a few years ago, Andrew Forte was one of them. Forte lives in Eufaula and grew up just north of town. Like me, Forte didn’t know about the Eufaula election massacre until he saw something about it on the internet.

Ironically, the correction might run afoul of the state’s recent Memorial Preservation Act, which forbids altering the appearance of any monument more than 40 years old. Purcell, who helped research the addition, says the addition is legal since it doesn’t touch the old monument. When I saw the granite slab, it could have fooled me.

But it demonstrates, perhaps as clearly as anything we’ve seen, history is not a granite soldier on a pedestal nor so much bric-a-brac in a pretty old house. Those are artifacts. History is something more complicated.

History is the backstory for everything that happens today — without it we can no more understand the present than keep up after walking into a movie that’s halfway over.

Today you can walk into the Alabama Legislature and see a body divided along racial lines. All but two Democrats are Black. All but one of the Republicans are white. The party labels have reversed, but the dividing line is in the same old place. And every year, the white folks run slap over the Black folks.

These things are not unconnected or unrelated.

Alabama is still Unreconstructed.

If Eufaula was ready to reckon with its history, it would have done so already, but its reluctance is understandable. Doing so is painful, even embarrassing.

But painful or not, acknowledging what happened there is necessary. Not to embarrass those with family ties to the murderers, but to honor the bravery of those new citizens who died trying to vote. Otherwise what you’re doing isn’t history, but a lot of “Gone with the Wind” cosplay.

It can hurt, and perhaps, the only way to tell you’ve found history and not its counterfeit, nostalgia, is when you discover something you didn’t want to see.

I get it.