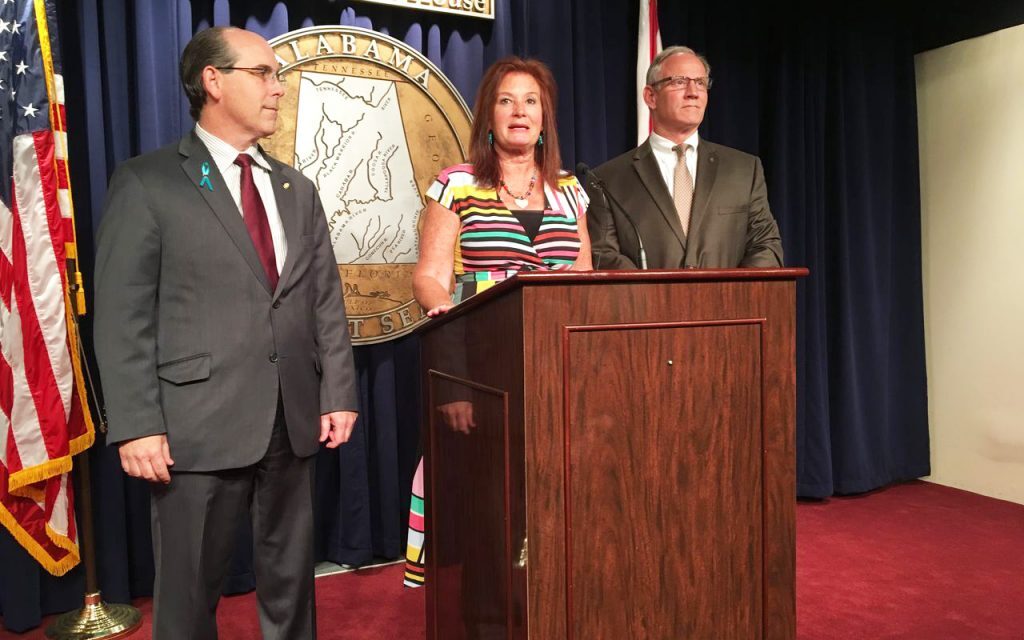

Rep. Terri Collins, the Decatur Republican who sponsored what was the nation’s strictest anti-abortion law in 2019, said she expects no exceptions for rape or incest will be considered until Alabama’s next legislative session begins in March 2023.

“I’m just celebrating life, and I’m celebrating that the ruling that Roe versus Wade has been overturned,” Collins said in an interview. “We are a long way from going back into session. It’s not until next March. And so we’ve got a lot of time to discuss how we want to move forward. I think we’ll learn a lot over these next few months as far as timelines and all and so for today, I’m just celebrating.”

When asked for clarification on whether exceptions to the law could be made sooner, Collins reiterated that the session begins in March. She said she is unaware of any new legislation surrounding abortion or birth control at this time.

In 2019, Gov. Kay Ivey signed Alabama’s Human Life Protection Act into law, which bans almost all abortions except when the pregnancy poses a serious health risk to the mother.

The law makes performing an abortion a Class A felony. Anyone administering an abortion could face up to 99 years in prison.https://www.youtube.com/embed/QED6z7yiymw?feature=oembed

While some Alabama officials have debated leaving room for abortions in cases of rape and incest, many anti-abortion advocates argue there should be no amendments to the law.

“We wanted a clean bill,” attorney Eric Johnston, who wrote the legislation, told AL.com in 2019. “We didn’t need amendments on it. That raised that whole rape and incest deal. It would be inconsistent to say that an unborn child is a person within the meaning of the Constitution, if it’s conceived by agreement or artificial insemination, but it’s not a person if it’s conceived by rape, incest or accident.”

He reiterated that the conception of the child, whether consensual or “an accident” does not warrant abortion protection to AL.com the day before the decision.

He and Collins said the bill’s ultimate goal was to assist in overturning Roe v. Wade.

After the Supreme Court’s ruling Friday, Attorney General Steve Marshall issued a statement that all current anti-abortion laws are now in effect and asked that the courts remove any injunctions previously attributed to Roe. v Wade protection. A judge removed a block several hours later. The 2019 law now takes effect.

“Any abortionist or abortion clinic operating in the State of Alabama in violation of Alabama law should immediately cease and desist operations,” Marshall said.

Two abortion care providers said Friday that they had stopped providing abortions, but still planned to offer counseling, birth control and other reproductive health services.

A near-total ban on abortion also puts Alabama’s high maternal and infant mortality rate in the spotlight.

Alabama’s maternal mortality rate is 36.4, ranking third highest in the country. Black women are more than twice as likely to die from pregnancy-related issues compared to white and Hispanic women, according to the National Center for Health Statistics. Since 2018, maternal mortality rates have increased for mothers from all demographics.

The state’s infant mortality rate is also higher than the national average. Alabama’s infant mortality rate is 7.18 deaths per 1,000 live births, ranking fifth worst in the country.

Fayette, Greene, Tallapoosa, Lowndes, Conecuh, Clarke and Washington counties all have at least 15 infant deaths per 1,000 live births, according to data from the Alabama Department of Public Health. The same report showed that in 2020, white babies had an infant mortality rate of 5.2 deaths per 1,000 live births, while Black babies died at twice the rate, or 10.9 deaths per 1,000 live births.

Alabama parents and families also experience high rates of premature births, underweight births and births of babies who did not receive any prenatal care.

“Now that we’re having the option and we’re being able to bring more of those children to life, we’re going to do exactly what you were saying,” Collins said when asked how the state will address health disparities. “We’re going to have to look for new ways to provide care for those families. And I know that while we’re not where we want to be as a state in our infant mortality rate and our mother, that we are moving in the right direction. We want to keep doing the things that promote healthy babies and promote healthy families.”

A 2020 report from the Alabama Department of Public Health indicated that maternal mortality rates had climbed significantly from 2012-16, according to data from the years covered by the report.

Collins said the state has been preparing resources for education and childcare.

“We’ve put a good bit of money into early childhood education and into quality childcare. And I know I’ve gotten several text messages, actually from attorneys, that are building coalitions of churches that are working to provide more adoptive and foster families,” she said. “I think you’ll see the same community that’s been praying for this to be overturned, unite and provide viable options for those families.”