By John Archibald, The Associated Press

(Joe Songer).

This is an opinion column.

Let’s be clear here.

Hillsboro is no Brookside. Nor is Town Creek or North Courtland.

Police in those towns – as far as we can tell – don’t routinely stop people on technicalities to take their stuff, toss them in a cold cell or regularly tow cars and drop drivers on the roadside to find their way home.

Hillsboro, Town Creek and North Courtland are speed traps, pound-for-pound the worst in the state, according to AL.com’s analysis of available data. They need you to speed to survive.

But those places are not just speed traps. They are symptoms of what happens when a state refuses to properly fund basic government and its justice system, when it won’t allow towns to adequately fund themselves.

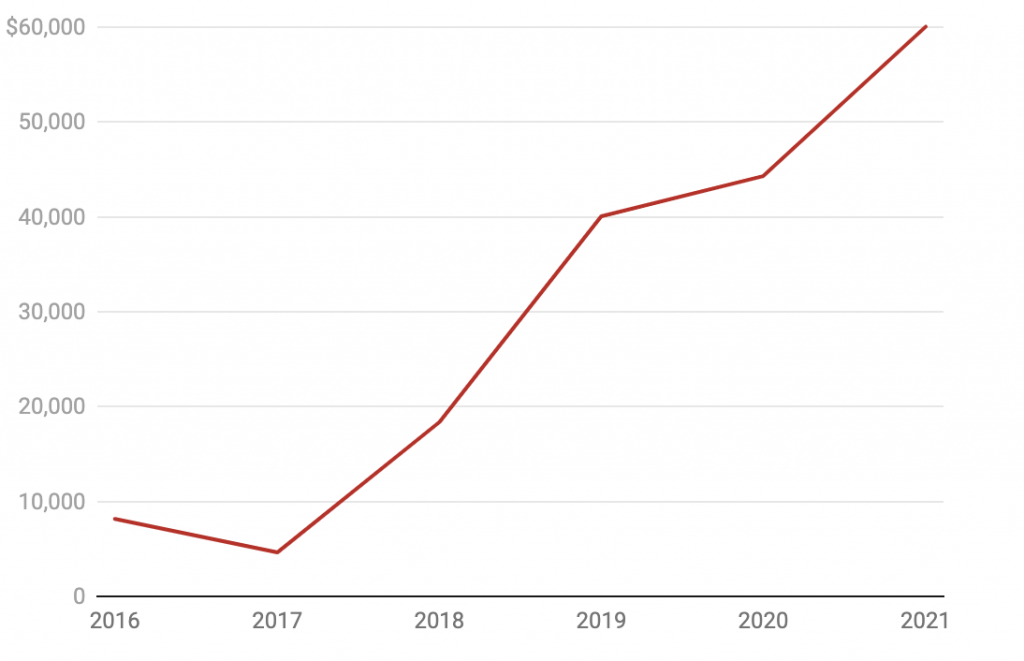

Face it. Under Alabama’s stifling constitution and its iron-fisted Legislature, there will always be a Hillsboro, where ticket money sent to the state finance department rose 1,197% between 2017 and 2021. There must be.

Hillsboro’s big jump

The amount of money Hillsboro’s municipal court sent to the Alabama Finance Department from fines and fees each year from 2016 to 2021.

There will always be a Town Creek, which in 2021 used traffic stops to collect $493,659, or $1,099 for every household in town. There will always be a Summerdale or Bay Minette on the way to the beach. There will always be an historically predatory Fruithurst, or a Harpersville, or a Castleberry.

Hell, despite the Legislature’s recent outrage over the aggressive policing – and abject meanness of Brookside – there will always be the threat of another one of those, too.

Because tickets and fines are big business. Too big to rein in.

Not just to small towns with no other source of income, but to counties and courts, to the state’s general fund and even the police officers’ pension, which gets $5 every time a ticket is paid. When the number of tickets given across the state of Alabama drops, a bevy of agencies suffers.

So tickets are protected in the sacred name of safety, and under the unassailable color of law, by everyone from local police chiefs to the attorney general, to dependent county commissioners and the Alabama League of Municipalities. Local ticketing is subsidized by millions of dollars a year in federal funding, passed to local police departments by the Alabama Department of Economic and Community Affairs.

Of course we want and demand that our highways be safe. But the end result is profit.

To fully understand it, you have to see the struggle over fines and fees.

Money from a traffic ticket is split by law between at least 16 separate agencies and funds. A $219 speeding ticket in a place like Hillsboro – not too different from any others – might bring as little as $17 to the town’s general fund.

Follow the money

Town ticket cash is split into a number of different funds, nearly all of which goes to the state.

So everybody wants more of the cut. Towns want more. Counties and courts want more, and the state depends on the tens of millions of dollars it gets every year from local tickets and fees. So many agencies across Alabama become so hooked on that cash that police have to make more and more “criminals” just to keep governments in the black.

But it doesn’t have to be that way.