Documents show overwhelmed, dysfunctional department

By Sarah Whites-Koditschek

The Alabama Department of Labor experienced significant technological issues and staffing shortages that led to delays and dysfunction during the COVID-19 pandemic, documents sent from the state to the U.S. Department of Labor show.

“Just before the pandemic hit, budget constraints dictated reducing an already strained workforce. Within months of the ADOL staff reductions, the state-mandated closures forced unprecedented claim loads,” the state department stated in a report to the federal department in February of 2022.

The problems at the department meant Alabamians who got unemployment help and are being billed for millions of dollars in overpayments have largely been without the ability to get a response to their appeals, according to delays detailed in correspondence between the state department and its federal counterpart.

In total, Alabama reported overpaying $164 million unemployment dollars to its residents between 2020 and 2021. Now it is asking for much of that money back.

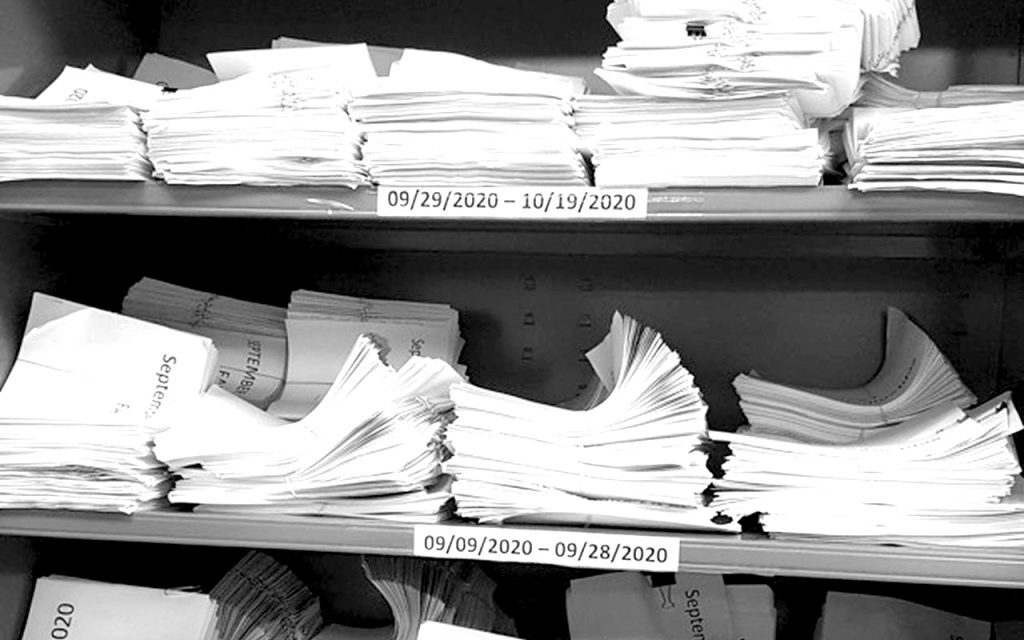

Yet many people told AL.com they get no response when they appeal. The department received “countless” appeals that had yet to be processed as of this year, according to data the department sent the U.S. Department of Labor, between December of 2020 and March of 2022.

The department reported it received but did not file at least 86,262 appeal requests.

As of June 3, 2022, there were just 12,715 appeals entered in the database pending a hearing.

The state department declined to share the total number of appeals requests it has received with AL.com, citing pending litigation.

“As the Alabama Department of Labor continues working to quickly resolve this issue and while the litigation is pending, we will need to defer back to our previous comments,” spokesperson Tara Hutchinson told AL.com in an email on Thursday.

“We do not plan to use the press as our means to respond to this litigation.”

Alabamians told to pay back unemployment

In its report to the federal department, Alabama explained that at the outset of COVID-19, it was in the process of modernizing its data system, which launched in January of 2020. The pandemic disrupted efforts to address problems with the new system, leaving the department scrambling to respond to overwhelming demand for unemployment.

Many Alabamians who received unemployment help during the pandemic have received notices from the department saying they were overpaid and must pay some of their unemployment money back, debts that often reach sums higher than $15,000 or $20,000.

Often overpayments are the result of small mistakes made by applicants, employers or the department. Alabamians can appeal their overpayment determinations, but because the state is behind on hearing appeals, many have been unable to contest the debts.

In 2021, Alabama was an average of 566 days behind on appeals, according to The Century Foundation’s analysis of federal data. In Kansas, appeals took on average just 15 days.

Following reporting on the overpayments by AL.com last week, Gov. Kay Ivey called the backlog “outrageous,” and called upon the Alabama Department of Labor to find solutions to the overpayment problem.

“We have asked (Labor) Secretary (Fitzgerald) Washington to provide us with solutions to resolve this concerning situation, as well as the outrageous backlog,” Gina Maiola, a spokesperson for the governor, told AL.com last Thursday, adding that Alabamians should not be made to pay for the governments mistakes.

“At the end of the day, the agency approved and paid out the claims.”

Following the message from Maiola last Thursday, the department told AL.com on Friday that it would explore the possibility of federal waivers to allow the state to forgive more of the overpayments.

“The department is currently looking whether to expand the use of allowed waivers pursuant to federal guidance,” said Joseph Ammons, general counsel for the Department of Labor.

Previously the department told AL.com it only grants waivers on a case-by-case basis and had not pursued a broad waiver to forgive most instances of overpayments during the pandemic.

States like Massachusetts, New Jersey, Florida and others have requested federal waivers to offer broad forgiveness to people who were overpaid unemployment during COVID-19.

Larry Gardella, an attorney with Legal Services Alabama said he would like the department to seek a federal waiver to forgive all the pandemic overpayments they possibly can.

“If they could do a broad waiver of all non-fraudulent claims, I think it would be a lot easier administratively, and it would certainly help claimants, and it wouldn’t cost Alabama any money. It’s all federal money,” he said.

Legal Services Alabama filed a lawsuit against the department earlier this year asking a Montgomery County judge to mandate the department to speed up its appeal processes and to make its communication and processes understandable for the average person. The judge is now weighing whether to dismiss the lawsuit pending against Labor Secretary Fitzgerald Washington on the basis of sovereign immunity.

“Plaintiffs have experienced extreme delays at every step of the unemployment process,” Legal Services Alabama stated in its complaint.

The department argued that it performed as well as it could have during the pandemic, and its officials are immune from the suit. The department saw a spike of 1,038,172 COVID related claims between April of 2020 and March of 2022, it stated in a motion.

“The Plaintiffs ask this Court to take over management of the Alabama Department of Labor,” the department stated in a filing in the suit. “In the wake of a once-in-a-century pandemic, ADOL faced a tsunami of unemployment claims.”

Department was inundated

To deal with its staffing shortages during the pandemic, the department asked its workers to do overtime and required all staff to take inquiry phone calls each day.

In February of 2022, the department reported to the U.S. Department of Labor it had an adjudication backlog of about 143,000 issues with its system.

Three common issues with applicants led to overpayment determinations, according to the reports. People who worked part-time often failed to report their part-time pay. Some beneficiaries failed to detail their work search efforts and some employers reported that their employees left for a reason other than “lack of work.”

Gardella said he would like the department to simplify its language and application processes to prevent overpayments in the future.

“To the extent clients do things wrong, they’re doing things wrong in large part because the department is making it hard for them to understand what they need to do,” he said.

Roughly eight months ago, in December of 2021, the department began scheduling hearings for appeals it received from the first few months of the pandemic through August of 2020. The department told the federal office that it must manually count appeals received by mail, fax or email.

“There is a countless number of appeal requests to be reviewed and entered in the database. The backlog of appeals is attributed to insufficient manpower to keep pace with the unprecedented volume of appeal requests resulting from the onset of COVID-19 in March 2020,” the department stated in its report to the U.S. department in February of this year.

The department stated that such backlogs explained why it was delayed in reporting mandatory data to the federal government and why it was behind in detecting overpayments.

“(This) combination of events left ADOL in a position such that the ability to detect recoverable overpayments has diminished.”

The department is responsible for catching overpayments, recovering the money and reporting data about these steps to the federal government.

In 2021, the department stated it prioritized flagging overpayments it made during the pandemic and sent notices to many Alabamians stating they were overpaid and would need to pay back the money.

The department pursued such overpayments before addressing the backlog of appeals, said Gardella, leading to a situation where people would be asked to pay back their overpayments before they could dispute the decision.

“(There was) this emphasis on spending a lot of time…on pursuing improper payments,” he said, “And less emphasis on getting people’s hearings heard so that the people who are entitled and haven’t been paid have the chance to get some money.”