By Frances M. Draper,

AFRO CEO and Publisher

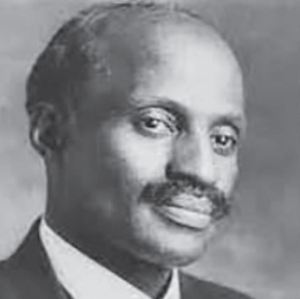

Tall. Dark. Handsome. Family man. No nonsense, but fair. Philanthropist. Ph.D. Farm Owner. Founder of a camp for children. Community leader. Beloved by students and teachers alike. These are just some of the words and phrases I’ve heard to describe my paternal grandfather, Francis Marion Wood. My mother once said that he was to education in Baltimore what Jackie Robinson was to baseball, an extraordinary “first.” Although he died before I was born, I have read several articles chronicling the positive impact he had on public education in Baltimore and beyond. He was a humble man, who rarely touted his accomplishments, preferring to applaud those he worked with, especially teachers and principals.

Grandfather Wood was born in Barren County, Ky. in 1878, the son of Fannie Myers Wood and William H. Wood. He was graduated from Glasgow High School and the State Normal School (now known as Kentucky State University). According to Wikipedia, he “received his Master of Arts degree at Eckstein Norton University in Cane Spring, Ky. in 1906 and began his career with a variety of positions in Kentucky education. He first worked as a teacher in a one-room log schoolhouse and continued teaching in rural Kentucky schools from 1896 to 1899. Next, he taught at Kentucky’s State Normal School from 1901 to 1907. He then served as a principal of Black elementary and high schools in Kentucky. This was followed by a promotion to serve as the state supervisor of Black high schools and rural schools. He then served as the president of the Colored State Normal School at Frankfort. He was also the president of the Kentucky Negro Teachers’ Association and a member of the Kentucky Commission on Interracial Cooperation. In 1924, he was also the Rockefeller Foundation student at the Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute (now Hampton University).”

In 1925, Dr. Wood was recruited by Baltimore City to become its Supervisor of Colored Schools at an annual salary of $4,200. He and his wife Nellie Virgie Hughes Wood made the trip from Kentucky to Baltimore with four young children, all under the age of 10. Three of his four children followed in their dad’s footsteps: John Wood was an educator like his father; his daughter, Iona Wood Collins owned and operated The Little School (the first African-American owned nursery school in Baltimore City); son, Albert Wood was a Baltimore City high school teacher; and, my dad, the youngest, James (Biddy) Wood was an entrepreneur and manager of several musical acts, including The Four Tops and his wife, Damita Jo.

According to a July 2, 1927 AFRO article, the Baltimore City School Board promoted Dr. Wood to be Director of Colored Schools in June of that year, making him the first African American to hold that post. Francis Marion Wood was a visionary and an expansionist. He is credited with doubling Black student enrollment in the Baltimore City Schools and pushing for schools to be named for prominent African and White Americans rather than just being known by their number i.e. Harriet Tubman, Harriet Beecher Stowe and Harvey Johnson. Although Dr. Wood was widely respected, numerous proposals for his promotion to assistant superintendent were denied by Baltimore’s all White school board.

The Maryland State Archives (MSA) reveals that one of Dr. Wood’s greatest accomplishments was the organization of the Baltimore City Teachers’ Association “and the stimulation of the extension courses for principals and supervisors under the auspices of Columbia University and the courses for teachers given by Morgan College and the University of Maryland.” MSA also notes that “in the midst of his life in the educational field, Dr. Wood finds time for church and community activities. He is superintendent of Union Baptist Church’s Sunday School, a member of the executive board of the YMCA, Association for the handicapped and the Urban League. He is also a Mason, K. of P., and Elk and a member of Alpha Psi Fraternity. A now-defunct summer camp for Baltimore City youth from low-income families was named for him, as well as several schools including the Excel Academy at Francis M. Wood High School in Baltimore City.

Francis Marion Wood died in 1943 and all city schools observed a five-minute moment of silence on the day of his funeral. Elmer A. Henderson, who was the principal of Booker T. Washington Junior High School at the time, succeeded him as director and was named assistant superintendent two years later.

Although I did not get a chance to meet my grandfather, I inherited his love for learning and for teaching. He is a little-known hero who had a big impact on public education in Baltimore. This edition features those who are the first and/or the few to do what they do. They are pioneers. They are creators. They are compilers. They are composers. Most of all, they are men and women who pushed through whatever fear they encountered to become and to do that which makes a tremendous difference in our world. Kirk Franklin and his unique touch on gospel music. Karine Jean-Pierre, the first African-American woman to be White House, press secretary. Alicia Hynson who finds her greatest joy in “birthing babies.” Be introduced to the first White House correspondents, the Black Press members who covered the Civil Rights Movement; and before you’re finished you’ll know the claim to fame of the Pitch and Putt Golf Club.

From the members who sell the ads to those who manage the classifieds, to those who pay the bills; the writers and the graphic designers. This is the “We’re Still Here” publication that celebrates Black History Month is the creation of the entire AFRO team, and for each of them, we are grateful.

Help us Continue to tell OUR Story and join the AFRO family as a member – subscribers are now members! Join here!

The post A little celebrated first: Dr. Francis Marion Wood appeared first on AFRO American Newspapers .

![“[Fashion Night Out] is basically just to celebrate fashion…it would be a great opportunity for us to get together and get everybody excited and information for these shows that will be one month later.”](https://nnpa.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/QUOTE-2-440x264.jpg)