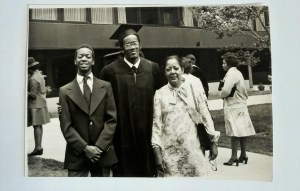

A young Wayne Dawkins, left, with his mother, Tompkins Park, Brooklyn, circa 1956. (Courtesy photo)

By Wayne Dawkins

Special to the AFRO

Here is a centennial story.

She never learned to drive a car and didn’t try.

Yet she traveled far and near, all over tri-state metropolitan New York, to Panama and to Canada, by bus, train and plane, and yes by car, if someone else was driving.

She wouldn’t balance a checkbook because checks could bounce, thus they were evil, she believed. Her second husband had a gambling addiction and at times played the lottery and lost the rent or grocery money, so she was wary. She paid bills by money order or cash. She taught her sons to keep promises and pay people back promptly, especially family and friends.

She was fiercely independent and self-governing. Don’t always follow the crowd; think for yourselves, she counseled. Avoid jealous urges when you see someone with something they have that you want. Are you willing to do whatever they did to get what they have? She’d ask.

And “God helps those who help themselves,” the Methodist-turned-Unitarian often would say, a phrase that so resonates during this to vax- or not-to-vax debate.

She loved arts and culture and shared it with her sons. The boys grew in the 1960s listening to Broadway show tunes on AM radio, which led at least one son repeat lines from “Oklahoma,” “South Pacific,” “Damn Yankees,” or “West Side Story.”

Musically, she adored Nat King Cole, George Shearing and Frank Sinatra.

She gathered her boys to see Shakespeare in Central Park on a warm mid-summer night, or shows at the BAM , or take them to the Brooklyn Children’s Museum, where the boys gained hands-on opportunities to sketch and paint.

OK, enough of this pronoun-only narrative. You probably figured out that I am talking about my mother, Iris Carmen McFarquhar Dawkins , a native of the former U.S.-controlled Panama Canal Zone. She was twice married to Jamaican men, including Edward Henry “King” Dawkins [1920-2003].

College graduation, Long Island University-Brooklyn, 1977. (l-r) Keith Dawkins, Wayne Dawkins and Iris Dawkins. (Courtesy photo)

On 9/11, mom was two weeks shy of her 80th birthday, yet this senior citizen was still going to a part-time job in Lower Manhattan. When the jetliners-turned-bombers crashed the World Trade Center Towers, mom was in a not-as-tall city government office building nearby.

She was helped down nine flights of stairs, then guided on a five-mile walk home to Brooklyn, across the Manhattan Bridge, during the state of chaos. Mom needed help, not so much because of her age, but because she was blind in one eye due to botched cataract surgery when she was 60-something.

In 2003, three of her four adult sons were summoned by a neighbor to do an intervention. Mom apparently had dementia. Severe memory loss had her behaving erratically, for example getting off at wrong subway stops along Brooklyn’s Eastern Parkway.

At her Sterling Place apartment, she shouted and resisted our pleas for her to enter an assisted living facility, but it only took 15 minutes for her to break down, sob and say, “I don’t know what I’m doing anymore.”

Mom surrendered. We found a satisfactory assisted living facility in Hollywood, Florida, where her “Long goodbye” was peaceful with loving, and sometimes comedic moments.

Mom’s short-term memory continued to deteriorate. She could not remember what was said in a 30-second conversation, but her long-term memory remained a vault of childhood memories.

Fortunately, when I visited, she didn’t reject me; she probably forgot I was her oldest Dawkins son, but knew I was family and no stranger.

Mom had bulging eyes that were perfect for physical comedy . She adored 1950s TV comedienne Imogene Coca.

“Let’s go for a drive,” she asked during one of my first Florida visits.

“OK,” I said.

Like a Warner Brothers cartoon character, she seemed to disappear in a puff of smoke, then return with her purse. She wanted to escape the confines, even if it was a 15-minute ride in my rental car. It brought her joy.

Mom’s legacy was education. When I finished fifth grade in 1965, I moved on to sixth grade at the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood junior high. JHS 33 was a blackboard jungle. My grades plummeted and I focused more on fight or flee behavior.

Mom immediately noticed the decline. She marched downtown to Board of Education headquarters and issued orders: You’ll transfer my son to that other school. The central bureaucracy that managed one million schoolchildren could not grind my mom under its wheels. Her instructions were followed.

Mom saved my life. I could focus on learning again. And I rejoined my Black friends who were bused to the predominantly White school in Bay Ridge.

Mom exaggerated. How could someone so cultured and literary be that way with merely the eighth-grade education she claimed?

Aunt Mabel, an ordained minister in Panama, said my mother actually completed high school and received post-secondary learning, however as oldest sibling, mom was the family caretaker. Her dreams of becoming a nurse were shelved. The younger siblings went to college, and she was peeved.

Still, Iris C. Dawkins left quite a legacy – four sons in varied white- and blue-collar professions, and adoption as “Moma D” because many adults made her their surrogate mom.

Wishing you love on your centennial.

The writer is a professor of professional practice at Morgan State University School of Global Journalism and Communication.

The opinions on this page are those of the writers and not necessarily those of the AFRO. Send letters to The Afro-American • 145 W. Ostend Street Ste 600, Office #536, Baltimore, MD 21230 or fax to 1-877-570-9297 or e-mail to editor@afro.com

Help us Continue to tell OUR Story and join the AFRO family as a member – subscribers are now members! Join here!

The post A cultural, principled and comical legacy appeared first on AFRO American Newspapers .