By Micha Green

AFRO D.C. and Digital Editor

mgreen@afro.com

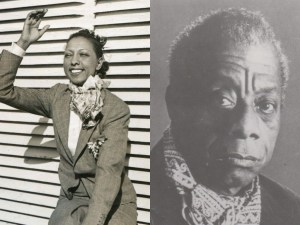

Black American art and artists have historically been lauded as the first of its kind then imitated by or duplicated for White performers and audiences. However, with the realities of American racism and prejudice, African American artists did not always have chances to thrive in their homeland and took to Europe to fulfill artistic dreams. Two such artists, Josephine Baker and James Baldwin, or for the purposes of this article- the JBs- fled the cold harshness of United States racism to the warm embrace of France and French culture. There, the two JBs were able to thrive as artists, speak to American racism and challenges, serve as positive representations of Black culture and become activists on U.S. soil and abroad.

Known for her flamboyant glitz and glam, Baker was not born into luxury. Born to a washerwoman and vaudeville performer, entertainment may have been in Baker’s blood, but money certainly was not. She was fatherless, living in poverty and in and out of school in adolescence. However, Baker was drawn to the luxurious lifestyle.

By 16, Baker took to the stage performing with a dance troupe in Philadelphia. In 1923, at 17, she began touring with the chorus of Shuffle Along, before moving to New York City and advancing on Broadway.

In 1925, Baker went to Paris to dance at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées in La Revue Nègre. There she introduced her “Danse Sauvage,” for French audiences.

According to the {Australian Ballet}, critic Pierre de Régnier described watching her perform the “Danse Sauvage,” as a contorted dance in continuous motion.

“She is in constant motion, her body writhing like a snake or more precisely like a dipping saxophone. Music seems to pour from her body,” the critic said. “She grimaces, crosses her eyes, wiggles disjointedly, does a split and finally crawls off the stage stiff-legged, her rump higher than her head, like a young giraffe.”

Baker then went on to wow in Folies-Bergère with her famous banana dance, when she entertained in a bikini top and short skimpy skirt made of bananas.

The star later said in a speech in 1963 that she was considered a “devil,” in her younger days of performing.

“Now I know that all you children don’t know who Josephine Baker is, but you ask Grandma and Grandpa and they will tell you. You know what they will say. ‘Why, she was a devil.’ And you know something…why, they are right. I was too. I was a devil in other countries, and I was a little devil in America too,” Baker said.

As a young celebrated celebrity, Baker continued to rock the Paris scene starring onstage and in film until World War II, which put her career on hold.

Baker worked with the Red Cross and Résistance during the German occupation of France and entertained troops in Africa and the Middle East as a member of the French Free Troops. For this work, she was awarded the Croix de Guerre and the Legion of Honour with the rosette of the Résistance.

Post war, the diva began to nest, focusing on Les Milandes, her estate in southwestern France. There she began to adopt children of all nationalities, beginning in 1950. Baker adopted 12 children, calling it her “rainbow tribe,” and defined it as “an experiment in brotherhood,” many sources reported.

Though she tried to retire in 1956, she began performing again in Paris in 1959, in order to maintain her estate and children.

Having been a French citizen since the 1930s, Baker still remained active in African American agendas and politics. Baker, like the other JB we’ll discuss in a moment, was a major leader in the American Civil Rights Movement. She was the only woman to speak at the 1963 March on Washington. In fact, she spoke right before the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his famous “I Have A Dream Speech.”

Baker addressed her move to Paris as a result of American racism in her speech at the March on Washington.

“And you must know now that what I did, I did originally for myself. Then later, as these things began happening to me, I wondered if they were happening to you, and then I knew they must be. And I knew that you had no way to defend yourselves, as I had,” Baker told the crowd, estimated to be upwards of 250,000 people.

“When I was a child and they burned me out of my home, I was frightened and I ran away,” Baker said a bit later in the speech. “Eventually I ran far away. It was to a place called France. Many of you have been there, and many have not. But I must tell you, ladies and gentlemen, in that country I never feared. It was like a fairyland place.”

She talked about going to Paris and not experiencing Jim Crow rules or disrespect due to her race, but dealing with extreme racism every time she returned to the United States, even as a star.

“You know, friends, that I do not lie to you when I tell you I have walked into the palaces of kings and queens and into the houses of presidents, and much more. But I could not walk into a hotel in America and get a cup of coffee, and that made me mad. And when I get mad, you know that I open my big mouth. And then look out, ‘cause when Josephine opens her mouth, they hear it all over the world,” Baker said.

The activist was accused of being a communist because she began raising awareness about discrimination. However, barrier-breaking Baker told the crowd that despite the hard time she was given for her activism, the world and Hollywood began to be more accepting of people of color.

“And when I screamed loud enough, they started to open that door just a little bit, and we all started to be able to squeeze through it,” Baker said.

The activist, mother and artist encouraged the young marchers to get a good education and continue fighting for justice.

“You must get an education. You must go to school, and you must learn to protect yourself. And you must learn to protect yourself with the pen, and not the gun. Then you can answer them, and I can tell you—and I don’t want to sound corny—but friends, the pen really is mightier than the sword.”

Baker continued her activism and performing in France until her passing in 1975. As part of celebrations acknowledging ther 50th anniversary of her Paris debut, Baker began doing performances at the Bobino Theatre in Paris. According to the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC), Baker had a wonderful performance and celebrated with late-night dancing and celebrity friends before going to bed, slipping into a coma and dying on April 12, 1975. She was 68.

“I am not a young woman now, friends,” Baker said at the March on Washington almost twelve years before. “My life is behind me. There is not too much fire burning inside me. And before it goes out, I want you to use what is left to light that fire in you. So that you can carry on, and so that you can do those things that I have done. Then, when my fires have burned out, and I go where we all go someday, I can be happy.”

One fire Baker ignited while alive was that of her dear friend James Baldwin. Though Baker was 18 years Baldwin’s senior, the Black Americans sparked a friendship that burned until Baker’s death.

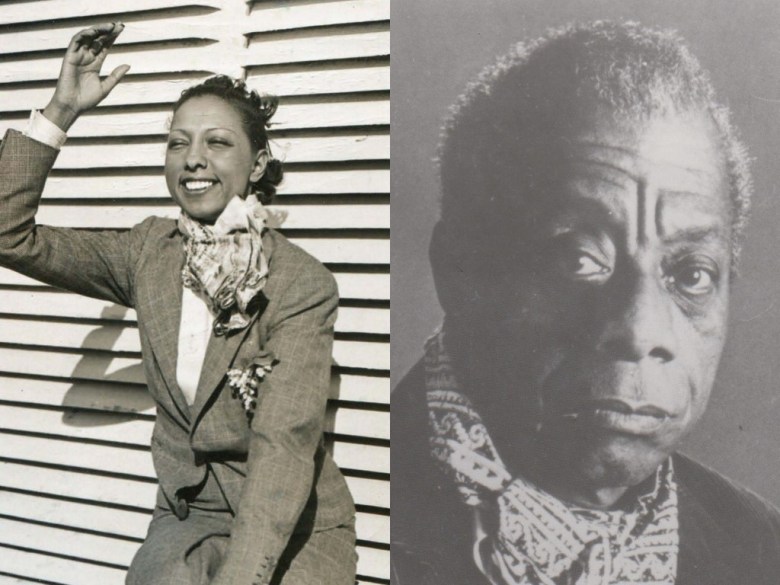

The Fire Next Time writer was born into poverty in Harlem on August 2, 1924. Throughout his adolescence and young adulthood, Baldwin navigated poverty, a strict family, religion, sexuality, racism and homophobia before retreating to France.

Baldwin’s stepfather was a Pentecostal minister who ran a religious, rigorous, rule-filled home full of nine children. The writer reflects on his upbringing in his writings, including the celebrated Go Tell it On the Mountain. Growing up, Baldwin loved reading, films and writing.

While Baldwin felt the streets of New York, living in poverty and exploring his sexuality was at times a distraction, during the summer of his 14th birthday, the writer experienced a religious transformation which led him to preaching, church work, and intentionally avoiding worldly vices. A smart student, Baldwin graduated from Dewitt Clinton High School in 1942, which, at the time, was an all boys high school in the Bronx.

After high school, Baldwin worked in the defense industry in Belle Meade, New Jersey, in order to support his family. It was there, Baldwin experienced racism, discrimination and segregation. Soon after his stepfather died.

Baldwin moved back to New York determined to be a full-time writer. As a Greenwich Village resident, Baldwin began working gigs and writing his novel. He met author Richard Wright of Native Sun fame, who helped him get the Eugene F. Saxton Fellowship, a $500 award that allowed him to help his mother and gave him the ability to finish the novel In My Father’s House. Harper Publishing, who sponsored the fellowship, chose not to publish the book, sending Baldwin into a drunken depression and writing hiatus.

In 1947, Baldwin took back to writing essays and reviews which were published and successful. The Nation even hired Baldwin on their staff to do book reviews, however he ultimately became disillusioned with the racism, homophobia and discrimination in the United States.

“I no longer felt I knew who I really was, whether I was really Black or really White, really male or really female, really talented or a fraud, really strong or merely stubborn. I had become a crazy oddball. I had to get my head together to survive and my only hope of doing that was to leave America,” Baldwin said, according to The Humanist.

“Once I found myself on the other side of the ocean,” Baldwin told the {New York Times}, per the Chicago Public Library. “I could see where I came from very clearly, and I could see that I carried myself, which is my home, with me. You can never escape that. I am the grandson of a slave, and I am a writer. I must deal with both.”

“In France, I am a Black American, posing no conceivable threat to French identity: in effect, I do not exist in France,” Baldwin told Le Nouvel Observateur in 1983.

Baldwin’s move to France, despite dealing with times of poverty, led to a creative boom with novels such as the first published novel Go Tell It on the Mountain and Giovanni’s Room, and his essays- which are lauded as some of Baldwin’s greatest contributions to the American literary canon. In addition to the aforementioned, “The Fire Next Time,” Baldwin’s celebrated essays include: “Notes of a Native Son,” “Nobody Knows My Name, “No Name in the Street” and “The Evidence of Things Not Seen.” Baldwin also had highly-lauded Broadway plays such as, “The Amen Corner” and “Blues for Mister Charlie,” which are still performed to this day.

Baldwin’s life pleasures in France and artistic success in the United States did not cloud his very real concerns about the plight of Black Americans. He, like Baker, was very involved in the American Civil Rights Movement- going to rallies, registering voters and serving as an outspoken critic on inequality and an advocate for Black Americans.

In the 1963 essay, “The Fire Next Time”, Baldwin writes: “You were born where you were born and faced the future that you faced because you were black and for no other reason. The limits of your ambition were, thus, expected to be set forever. You were born into a society which spelled out with brutal clarity, and in as many ways as possible, that you were a worthless human being. You were not expected to aspire to excellence: you were expected to make peace with mediocrity.”

Baldwin was present for the 1963 March on Washington, but was not allowed to speak due to concerns that he would be too inflammatory in word choices and addressing the issues.

A quote that Baldwin said in a 1969 interview still resonates to this day. “The (police) are a very real menace to every Black cat alive in this country,” Baldwin said in a Dick Cavett interview according to PBS. “And no matter how many people say, ‘You’re being paranoid when you talk about police brutality,’ – I know what I’m talking about. I survived those streets and those precinct basements and I know. And I’ll tell you this- I know what it was like when I was really helpless, how many beatings I got. And I know what happens now because I’m not really helpless. But I know too, that if he (the police) don’t know that this is Jimmy Baldwin and not just some other nigger he’s going to blow my head off just like he blows off everybody else’s head,” he said.

“For me this has always been a violent country- it has never been a democracy,” Baldwin added in 1969.

After the passing of his friends and Civil Rights leaders, Medgar Evers, Malcolm X and King, Baldwin became even more disillusioned with the United States and lost hope with the freedom fight. Though he spent most of his time in France, Baldwin remained an American citizen and was said to consider himself more of a commuter than an expatriate.

France gave Baldwin his flowers while he was still alive to smell them. He was given an honorary PhD from Nice University in 1982 and France made him a Knight of the Legion of Honour, dubbing him for achievements in the arts in 1986.

Baldwin died from cancer in 1987.

Even years after their passing, Baker and Baldwin remain integral to Black, American, French and global culture.

In 2017, the film I Am Not Your Negro was released based on Baldwin’s unfinished book “Remember This House,” which was to be a personal account on the lives of his friends Evers, Malcolm X and King.

Baldwin’s fifth novel, If Beale Street Could Talk (1974), was recently recreated and released as a film in 2019, which garnered actress Regina King an Academy Award, Golden Globe and Critics’ Choice Movie Award for Best Supporting Actress and Best Director awards for Barry Jenkins, who also received a Critics’ Choice Movie Award for Best Adapted Screenplay.

In November 2021, Baker was announced as the first Black woman to be interred in France’s Pantheon.

“The times are probably more conducive to having Josephine Baker’s fights resonate: the fight against racism, antisemitism, her part in the French Resistance,” essayist Laurent Kupferman, who advocated for her inclusion in the Pantheon, told The Associated Press. “The Pantheon is where you enter not because you’re famous, but because of what you bring to the civic mind of the nation.”

Help us Continue to tell OUR Story and join the AFRO family as a member – subscribers are now members! Join here!

The post Josephine Baker and James Baldwin: The JBs take France, become activists, make America appreciate them appeared first on AFRO American Newspapers .