By Ryan Michaels | The Birmingham Times

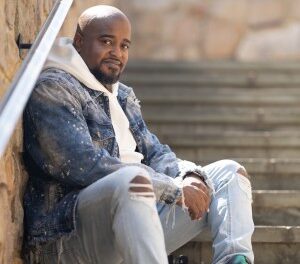

Looking back, Adolphus Jackson, D.M.D., first decided he was going to be a dentist while an elementary school student in Birmingham’s Rising-West Princeton community. Now, he’s president of the Alabama Dental Association (ALDA)—the first Black person to assume the post.

“Alabama has realized [that] it doesn’t matter what color you are. They have realized that leadership is leadership whether you’re Black or white, so becoming president has really made me realize my association has come to grips with that,” Jackson said in an interview with The Birmingham Times.

As president of the ALDA, Jackson wants to focus on getting more dentists into rural areas, as well as helping young dentists transition into senior roles.

Since opening his clinic—the West Princeton Dental Clinic in Birmingham’s West End community—in 1987, Jackson has remained dedicated to his work because of what it means for residents.

“I think it’s the joy of helping someone to increase their self-esteem because a beautiful smile always gives you great self-esteem,” he said.

Need for Black Doctors

Jackson, 67, knew at a young age what career path he would choose. As a sixth grader attending a career fair at Princeton Elementary School, he listened to a presentation given by representatives from the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB).

“[UAB] did a survey that showed there was a shortage of Black dentists. At that point, I knew I wanted to go into a medical career and made up my mind then that I wanted to be a dentist,” he said. “My fifth-grade teacher always told me that I should set my goals on becoming a dentist.”

Jackson graduated from West End High School, where he was elected the first Black president of a senior class. He then attended Fisk University, in Nashville, Tennessee, where he earned a bachelor’s degree in chemistry. After completing his undergraduate studies, Jackson returned to Birmingham and earned a doctorate in dentistry at UAB in 1980; joined the U.S. Navy to provide dental care for servicemen and served as an officer; but the road always led back to the Magic City.

“In my mind, there was always a need to have Black health care professionals in our community and to service our people,” said Jackson.

He grew up during the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s, recalled the “racial tension” of the time and fondly remembered his teachers.

“We had very great educators in the school system,” said the doctor. “… they always encouraged us to reach higher and go further, so I didn’t think [growing up during that time] was a disadvantage at all.”

Throughout his career, which has spanned more than 40 years, Jackson has served as a medical missionary to several countries, including Ghana, Liberia, and Haiti. On a missionary trip to Maracaibo, Venezuela, in the 1990s, Jackson said he was particularly moved.

“It was overwhelming to see that people had been traveling for weeks just to know that we were coming to do dental service,” Jackson said. “They traveled from mountains for weeks, and it overwhelmed me that the need was just that great. … It was overwhelming because the lines were so long.”

On that trip, Jackson said he and the other missionaries started work at 7:30 a.m. and continued until the sun went down because there was a lack of adequate lighting: “I can’t even imagine how many people we received.”

Giving Back

Jackson is the son of Wilbur Sr., who worked for U.S. Steel, and Rosa Belle, who was a homemaker for her family, as well as around her community.

Today, Jackson and his wife, Diann Dixon, have six children of their own—Jasmine, Adolphus, Justin, Charity, Julian, and Joy Rosa, all ranging in age from 26 to 40. They also have two grandchildren: Olivia and Lyric. Jasmine, Adolphus, and Justin all work in health care. Julian is in dental school, Joy Rosa is in medical school, and Charity is a teacher at the Magic City Acceptance Academy in Homewood, Alabama.

Jackson said he has tried to set an example for his family, “making sure they know, first off, that God is their provider. That was my first thing to make them realize. … Second, [I’ve encouraged them] to help someone else achieve things in life. Giving back is most important, and the health care profession is always giving.”

He’s given of his time across numerous dental organizations in Birmingham and Alabama.He is a member and past president of the Birmingham Chapter of the National Dental Association (NDA), which was formed in 1913, when Black people were not allowed to join the American Dental Association, making Jackson’s role as president of ALDA that much more significant. The NDA still exists today as an organization for minority dentists.

He is a member and past president of the National Dental Association House of Delegates, as well, and he has been part of the Birmingham District Dental Society.

Currently, he serves on the University of Alabama School of Dentistry Leadership Council. He previously served on the Alabama Board of Dental Examiners from 2014 through 2019 and held the position of president from 2017 to 2018, as well as on the Commission on Dental Education (CODA) as an American Dental Association Commissioner among other groups.

“I didn’t realize I was in so many serving organizations,” he said. “I was like, ‘Gosh, everything I’ve done is [service].’ I should have joined an organization just for fun; each one I’ve joined requires a lot of work. I should have joined a boating or hunting group or something like that—sailing, bowling, anything,” Jackson said, with laughter.