By Je’Don Holloway Talley

For The Birmingham Times

Jason Ikeem Rodgers clearly remembers the epiphany he had that led him to create the Atlanta, Georgia-based African American ensemble, Orchestra Noir.

He and his wife, Keisha, were invited to an elegant soiree in an affluent neighborhood that was attended by some of the city’s elite: “It was a classy event, and, for the first time, I saw the real Black middle class,” Rodgers recalled of the gala.

“I saw these Black, educated people, and they were in tuxedos. … It was a very glamorous event, and that’s when it popped in my head: ‘Orchestra Noir, the Atlanta African American Symphony,’” he said. “[I said it out loud], and my wife was like, ‘What are you talking about?’ I said, ‘That’s the orchestra. We need to build [a Black] orchestra here in Atlanta and have it for Black folks.’”

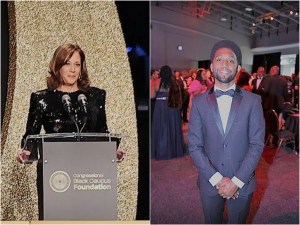

Rodgers, 39, CEO, founder, and music director of Orchestra Noir, knew exactly the type of orchestra he had in mind.

“We could do [Ludwig van Beethoven, a German pianist and composer], [Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, an Austrian composer], and all that stuff, but it also needed to reflect Black composers, Black musicians. … It had to be all-Black and showcase Black talent in an orchestral way,” he said.

By the way, the young lady who had invited Rodgers and his wife to the gala never showed up at the event, he recalled with a laugh. It didn’t matter, though. Attending the gathering gave birth to an idea that has now become a groundbreaking ensemble, which is making its mark in the symphony orchestral world with its first-of-its-kind musical act.

Orchestra Noir makes its Birmingham debut with “The Best of Hip-Hop and R&B” concert at the Lyric Theatre on May 7 at 8 p.m. The ensemble will deliver its signature curated sound, which is a fusion of classical orchestra pieces combined with the familiarity of hip-hop anthems and R&B favorites.

There’s a reason Rodgers’s vision to create an eclectic symphony experience for the Black audience has become a fan favorite and performs to sold-out shows.

“The way we rehearse and organize our music is very different,” said Rodgers, who is also known as “The Maestro.” “Usually, in an orchestra somebody will write all the music down and give the parts to the players, [who] play what’s on the page. We have a different culture in Orchestra Noir, where I might write some things down, but I leave it open for free thought. I might ask the bass player, ‘What do you think of the bassline over there?’ or I might ask a violinist [for their thoughts]. … It’s a collective of musical ideas and input within the orchestra.”

Growth

Following his epiphany at the Atlanta gala in 2016, The Maestro wasted no time putting together his orchestra. It took him four months.

“We started off with 10 players, and it started to grow,” Rodgers said. “We had our first show in 2016 at a small venue, and no more than 100 people [attended]. We had a string quartet that did classical and then branched off into some R&B. At the next show, 400 people [were in attendance]. Atlanta just took to what we were trying to do.”

Six years later, Orchestra Noir is comprised of 50 pieces, with the addition of a few non-traditional elements, such as the sousaphone (a strap-on tuba), the drums, and the saxophone. Asked if their music body has any soloists or ascribes to the music mantra “one body, one sound,” Rodgers said, “It started off like that, but we had players emerge to be my main soloists.”

One of those soloists is saxophonist Larry J. Smith, who serves as assistant music director.

“He was one of the voices I realized early on,” Rodgers said. “I kept hearing a saxophone [while writing arrangements] before we met Larry. … Usually, I would let strings be the lead. As I kept hearing the different voices in the music in my arrangements, I said ‘Let’s look for a saxophonist.’ Luckily, we met Larry. We saw him on social media and reached out. He joined the team and had organic chemistry from the very beginning.”

Another soloist Rodgers pointed to is keyboardist Tyrone Bowie, a Birmingham native who serves as the keyboardist and band coordinator.

“I liked his sound and versatility,” Rodgers said. “This guy can play anything. Name any song, and somehow he can just play it from his head.”

“Conscious Decision”

The Philadelphia, Pennsylvania-born music innovator comes from a family of performers and ultimately gained his first exposure to the piano by watching his relatives.

“I had eight aunts and two uncles, and they all sang or played instruments in the church,” Rodgers said. “My grandmother was a pianist, and she taught my mother how to play the piano. [They] were gospel pianists. I wanted to learn how to read music and learn in a very formal way. I don’t think my mother and grandmother knew how to read music.”

The first time Rodgers heard classical piano being played by his middle school music teacher, Ms. Virginia T. Lam, it expanded his taste in music and changed his life. He was 10 years old.

“It really intrigued me, and I wanted to learn how to play it,” Rodgers recalled.

“I liked to get into trouble as a kid, so when I told my music teacher I wanted to play, I don’t know if she believed me at first. I had to beg her every day after school to teach me. I even jumped on the hood of her car when she was leaving one day, and I was like, ‘Can you teach me this piano?’” he laughed.

His teacher teacher-turned-lifelong-music-mentor began with the basics.

“[Ms. Virginia] started me on piano and noticed that I was growing pretty fast because my abilities, after a couple of years, had surpassed hers,” Rodgers said. “She took me to see this Ukrainian teacher, Ms. Irene Porkovsky [of Philadelphia’s Settlement Music School], and I studied under her for five years.”

In the 11th grade, Rodgers made a “conscious decision” to pursue music.

“That’s when I knew I was going to go to college for it,” he said. “Ms. Virginia asked me, ‘Do you want to pursue music as your life? If you do, I’ll show you how to do that, how to go to college and major in it. I’ll go with you to all of your auditions, and we’ll make this a reality because you have the talent.’

“She helped me fill out college applications. We took the train or plane to all the different colleges I had to audition for in person. … She was with me through that whole process and is still my mentor to this day. She even joined my staff [as the production manager] and is on my board. … She’s been an anchor in my life. She’s like a mother, I call her mom now.”

Rodgers also credits Lam for helping him become a music teacher—for a while, at least.

“When I was 27 and coming out of college, Ms. Virginia got a huge promotion and became the music supervisor of the [School District of Philadelphia]. … I said, ‘I’ve got these music degrees, but I don’t have a job.’ So, she said, ‘Why don’t you audition for the school district, and you can become a music teacher?’ … Who was the one auditioning me? It was her!” Rodgers laughed.

“I was a music teacher from [ages] 27 through 30,” he recalled. “At 30, I decided I was going to go to Europe, try my luck, and see how good I really was. When I won first prize [in a competition], I said, ‘This is my calling.’ … I never looked back.”

Rodgers has performed with orchestras in North America and abroad and has received numerous accolades, including first prize in the London Classical Soloists Competition in 2015, winner of the International Conducting Competition held in the U.S. in 2014, and first prize in the Orchestra da Camera Fiorentina Conducting Competition held in Florence, Italy.

A formally trained classical pianist, he earned a bachelor’s degree in piano, a master’s degree in conducting from the University of North Carolina School of the Arts, and a Professional Studies degree in Conducting from the Cleveland Institute of Music, in Cleveland, Ohio.

Representation

Rodgers sees beyond his role as a maestro. His vision includes representation.

“When young brown girls and boys aspire to be musicians [and can] see somebody up there that looks like them, that says so much,” he said. “When they see people that look like them playing Mozart, Beethoven, and violins, as well as playing hip-hop and R&B, they’ll say, ‘Wow, I want to do that.’ … A lot of that is in representation. If you don’t see people who look like you doing that when you’re a child and very impressionable, you may get discouraged. So, if I can inspire young Black kids, that’s major.”

Rodgers is also aware of the challenges Black musicians face within the orchestral community.

“It’s been said in America that orchestras are only 1.8 percent African-American. Every major city in America has an orchestra, and it’s not diverse yet. So, of course, there are challenges,” he said.

After graduating from college, Rodgers faced difficulties finding work, as well, but he did not let that stop him.

“It was at the beginning of my career, and that process is about who you know,” he said. “If you don’t know the right people, you’ll have a hard time. I noticed that watching other conductors [struggle] to make a living. … Building Orchestra Noir was my way to combat that. I started trying to do it my way instead of going the traditional route. I didn’t want to wait for the mainstream orchestral community to accept me. I found a way to do it on my own.”

Orchestra Noir makes it Birmingham debut with “The Best of Hip-Hop and R& B” concert on May 7 at 8 p.m. at the Lyric Theatre. To learn more about Orchestra Noir, visit www.orchestranoir.com ; email info@orchestranoir.com; call 770-802-8149; or follow on Facebook (www.facebook.com/orchestranoir) or Instagram @orchestranoir.