State Rep. Chris England is prone to wander. It’s something he enjoys doing, exploring backroads and forgotten sites in a state that still confounds him.

It’s not always the safest pastime.

“You’re going to think I’m crazy,” he says.

Not long after he was first elected in 2006, England, a Democrat from Tuscaloosa and now state party chairman, toured Alabama’s Emergency Management headquarters near Clanton. After the stop at EMA, he meandered.

“I also visited the — you know the big flag on 65?” he says.

If you’ve driven the interstate between Birmingham and Montgomery, you know the big flag. It’s impossible to miss. Raised there by the Sons of Confederate Veterans, it might be the state’s most unsightly roadside distraction.

Hoisted on a 100-foot pole, the 600 square foot Confederate banner flies over private property, so England moseyed further until he came to a cemetery where much smaller battle flags flapped from wooden sticks by the graves of long-dead soldiers. He got out to look around.

“I walked through it, and I just looked at some of the names, just to kind of get a feel for what this is about, why we struggle for this. Right?” he says. “I never got an answer.”

That’s when the men in two pickup trucks pulled up. They didn’t get out at first, but they stopped and stared at him, he says.

“What can I do? I’m out here in the middle of the woods, by myself, at a Confederate cemetery, essentially,” England says. “So I did the only thing I knew to do — I tried to make sure that I humanized the situation, let them know that I wasn’t here to kick over tombstones and knock stuff down.”

There are still places and situations where it’s unsafe for a Black man to go. And if that seems like an exaggeration, look one state over, to Georgia, where Ahmaud Arbery lost his life for exploring a house under construction. Or to Florida, where Trayvon Martin was killed on his way home from buying a pack of Skittles.

England waved at the men. They waved back. Then one of the men got out of his truck and asked him what he was doing.

“I said, ‘I’m just trying to get a better appreciation for Alabama’s history,’” England says.

The men laughed and England smiled back at them. They chatted a bit more before they got back in their trucks and left. “I was scared shitless though,” he says.

Even in 2022, Black people must live with the fear that there are places where they could be killed before they might explain what it is that they’re doing there. What a lifetime of living with that pressure will do to a person is something England wants his white colleagues in the Legislature to understand.

It’s a struggle he seems to be losing.

In successive legislative sessions, Black lawmakers have grown increasingly weary of serving as political tackling dummies, run over repeatedly by an increasingly dismissive majority.

It’s a struggle that, months after England told me this story, would lead to several Black lawmakers telling their white colleagues they’d never be able to look at them the same way again.

England was one of them.

Same turning point, different year

In 2019, the Alabama State Senate was debating yet another abortion bill when something curious happened. The text of the bill compared abortion to a handful of crimes against humanity.

“It is estimated that 6,000,000 Jewish people were murdered in German concentration camps during World War II; 3,000,000 people were executed by Joseph Stalin’s regime in Soviet gulags; 2,500,000 people were murdered during the Chinese ‘Great Leap Forward’ …”

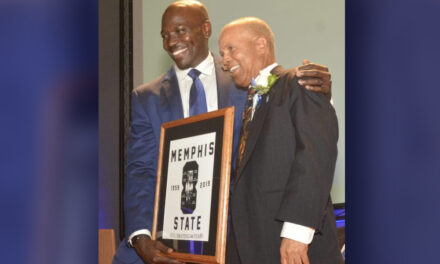

Sen. Rodger Smitherman, D-Birmingham, noticed something missing. He proposed an amendment to include the transatlantic slave trade among the atrocities. After all, it’s estimated that at least 2 million enslaved Africans died crossing the Atlantic in what’s called the Middle Passage.

The bill’s Senate sponsor, Clyde Chambliss, R-Prattville, opposed the amendment, which failed on a party-line vote. The Senate chambers grew quiet and uncomfortable. The abortion bill debate had been tense already, but after Smitherman’s amendment died, there was a sense that something much more personal had happened and the tone carried through the rest of that session.

Similar inflection points have become a mid-session phenomenon in Montgomery.

On paper, Alabama has a two-party system, and in the Alabama Legislature, there are Republicans and Democrats. But were someone wholly unfamiliar with Alabama to walk into the Statehouse there’s one thing they’d notice immediately.

All but two of Alabama’s Democratic lawmakers are Black. All but one of Alabama’s Republican lawmakers are white.

And the white ones are firmly in the majority.

It’s a political divide that sometimes expresses itself in unexpected moments — when gambling legislation threatens to close casinos in majority Black counties, or when Medicaid expansion, which could have brought billions into Alabama, is ignored.

“You have to take things issue by issue,” Smitherman, who has served in the Senate since 1994, told me later. “You can’t take things personally, because I might disagree with you on one bill and need your support for another.”

This sort of emotional compartmentalization is more common among older Black lawmakers. Some younger Black lawmakers have found the nothing-personal approach harder to maintain.

The 2021 regular session saw tempers flare over a bill to raise criminal penalties over rioting. Among other things, the bill increased penalties for blocking highways during protests, and Democrats asked how the bill would have applied to Selma-to-Montgomery civil rights marchers. Rep. Mary Moore, D-Birmingham, speaking on the House floor, called the bill’s sponsor, Allen Treadaway, R-Morris, a racist. The two exchanged words.

In another exchange, Rep. Merika Coleman, D-Birmingham, lashed out at Rep. Charlotte Meadows, R-Montgomery, who had been needling her and other Democrats throughout a late-night session.

“I will not take it,” a frustrated Coleman told Meadows. “We, as a body, shouldn’t take it. And just because you’re a white woman doesn’t mean you know more than I do as a Black woman.”

Meadows laughed at Coleman, making Coleman even angrier as lawmakers, white and black, squirmed.

Throughout the session, England and House minority leader Anthony Daniels, D-Huntsville, pulled their colleagues aside, talking to them in the aisles, counseling them on keeping cool.

“Folks like to say that this is like professional wrestling, that what you see isn’t real,” England told me after the 2021 session. “Well, now people are starting to get hurt.”

The riot bill passed the House but died upstairs in the Senate.

Meanwhile, Smitherman pushed through a bill to create a police brutality database so bad-apple law enforcement officers could no longer quietly evade accountability by jumping from one department to another. It was the only one of six bills Democrats introduced in the wake of George Floyd’s murder that passed.

England counted both as victories, however fleeting.

“I also know that same spirit will reappear in 2022,” England predicted last year. “Not just in a riot bill, but in a CRT bill, too.”

Telling one CRT from another

This is the part in stories like this where I’m supposed to turn down the lights and turn on the overhead projector and explain what critical race theory is and what it isn’t.

Critical race theory is confined mostly to higher-level graduate courses and to law schools. An esoteric framework, critical race theory examines how bias in law and social structures disadvantages minorities more than white people. Critical race theory is not taught, nor has it ever been taught, in Alabama K-12 schools …

Only, nobody gives a damn about any of that.

Because CRT has become something different now. To understand what this other CRT is, it helps to watch a few campaign ads.

In her latest TV spot, Gov. Kay Ivey stands in front of a classroom. She begins by briefly mentioning her time as a teacher decades ago.

“When I taught school, we said a prayer, pledged allegiance and taught the basics,” she says.

Then Ivey takes an aggressive turn.

“Today the left teaches kids to hate America, ” she growls like a substitute teacher who might smack a kid with a ruler. “But not here! Biden’s critical race theory — racist, wrong and dead as a doornail.”

I should have mentioned during the classroom lecture, Joe Biden did not invent critical race theory, nor has he advocated using it in schools.

The ad is the latest among Ivey’s claims to have “banned” critical race theory from schools, which is curious since Ivey has done no such thing.

Ivey hasn’t yet signed any anti-CRT bills into law, although she could soon have the opportunity.

Ivey hasn’t issued any executive orders banning CRT in the classroom, either.

The closest Ivey has come to restricting CRT was an administrative resolution, passed by the Alabama State Board of Education, on which Ivey serves as president.

That resolution, titled “Declaring the Preservation of Intellectual Freedom and Non-Discrimination in Alabama’s Public Schools” doesn’t mention CRT, nor does it ban it from classrooms. Instead, it prohibits “divisive concepts,” a euphemism that often stands in the place of CRT throughout the country.

But something important must not be lost amid the misdirection: The Alabama school board’s CRT ban does not, in fact, ban CRT.

So what’s going on here?

Mostly, it appears to have been fodder for Ivey’s ad.

The so-called CRT ban gives Ivey a hook — however small — on which to hang her claim.

And it allows Republicans, such as her, to accuse Democrats of something they never did.

Democrats — which in Alabama politics, means mostly Black people.

CRT is the mechanism Republican candidates can use to accuse Black people of being the real racists. And it has become an essential tool for Republicans going into the 2022 primaries.

The trouble in Alabama, though, is that Ivey has a CRT claim she can make, however specious — but Republican lawmakers can’t say the same. The issue is still so new that no one thought to drop an anti-CRT bill in the 2021 Legislative session.

But in 2022, just as England predicted, the Alabama Republican supermajority brought a bill to ban a thing that their governor is on TV saying has already been banned.

And just as CRT is something different for Republicans than the critical race theory taught in higher education and law schools, the issue has become something different for Democrats, too.

For Black lawmakers in Alabama, it’s a struggle for respect.

Three times in a committee

When the Alabama House’s State Government Committee first took up HB 312, committee chairman Rep. Chris Pringle, R-Mobile, made a promise to his Democratic colleague, Rep. John Rogers, D-Birmingham.

“I promise you, I’m going to give you all the time to debate this bill that you want,” Pringle said.

We’ll be coming back to that. The Republicans’ vehicle for a legislative CRT ban, HB312, would go before the committee three times.

The first was for a public hearing, when concerned constituents may speak their mind about a bill. Eleven people spoke before the committee, including a lawyer, several teachers and the state director of Archives and History, Steve Murray.

All of them opposed the bill.

In the second meeting, committee members debated the bill among themselves. Several Black lawmakers quizzed the bill’s sponsor, Rep. Ed Oliver, R-Dadeville, about what his bill actually does. Oliver struggled to give examples of the divisive concepts he opposes.

“With all due respect,” Oliver said, a retired ambulance helicopter pilot. “I’m trying to protect students in this day …”

“From?” asked Rep. Rolanda Hollis, D-Birmingham.

“From different ideologies I do not think are appropriate,” he said.

“Like?” she asked.

“From socialism or communism or anything else,” he said.

By this point in the legislative process, Oliver’s bill had become so watered down that even he said it read more like the Civil Rights Act than a groundbreaking new law. In the second committee meeting, Oliver removed language calling slavery a deviation from the founders’ principles since the Constitution’s three-fifths compromise pretty much nullified any such argument.

The important thing here was that they pass something.

What the bill would actually do after the inevitable press release it was meant to generate seemed almost irrelevant.

But Oliver and the bill’s supporters had reason to know what the side effects of this bill might be. Earlier in the session, Alabama State Superintendent Eric Mackey told lawmakers, including Oliver, that the school board’s existing anti-CRT resolution had already triggered complaints about Black history being taught in schools.

“There are people out there who don’t understand what CRT is, and so in their misunderstanding of it, they make a report but it’s not actually CRT,” Mackey said then. “I had two calls in the last week that they’re having a Black History Month program and they consider having a Black history program CRT. Having a Black history program is not CRT.”

Alabama Archives and History Director Steve Murray gave the State Government Committee a similar warning.

“It will lead to teachers spending more time trying to determine where the mines are in the minefield, so they don’t step on them and inadvertently get themselves or their school in trouble, than they will spend time preparing good lessons in history education and civics,” Murray said.

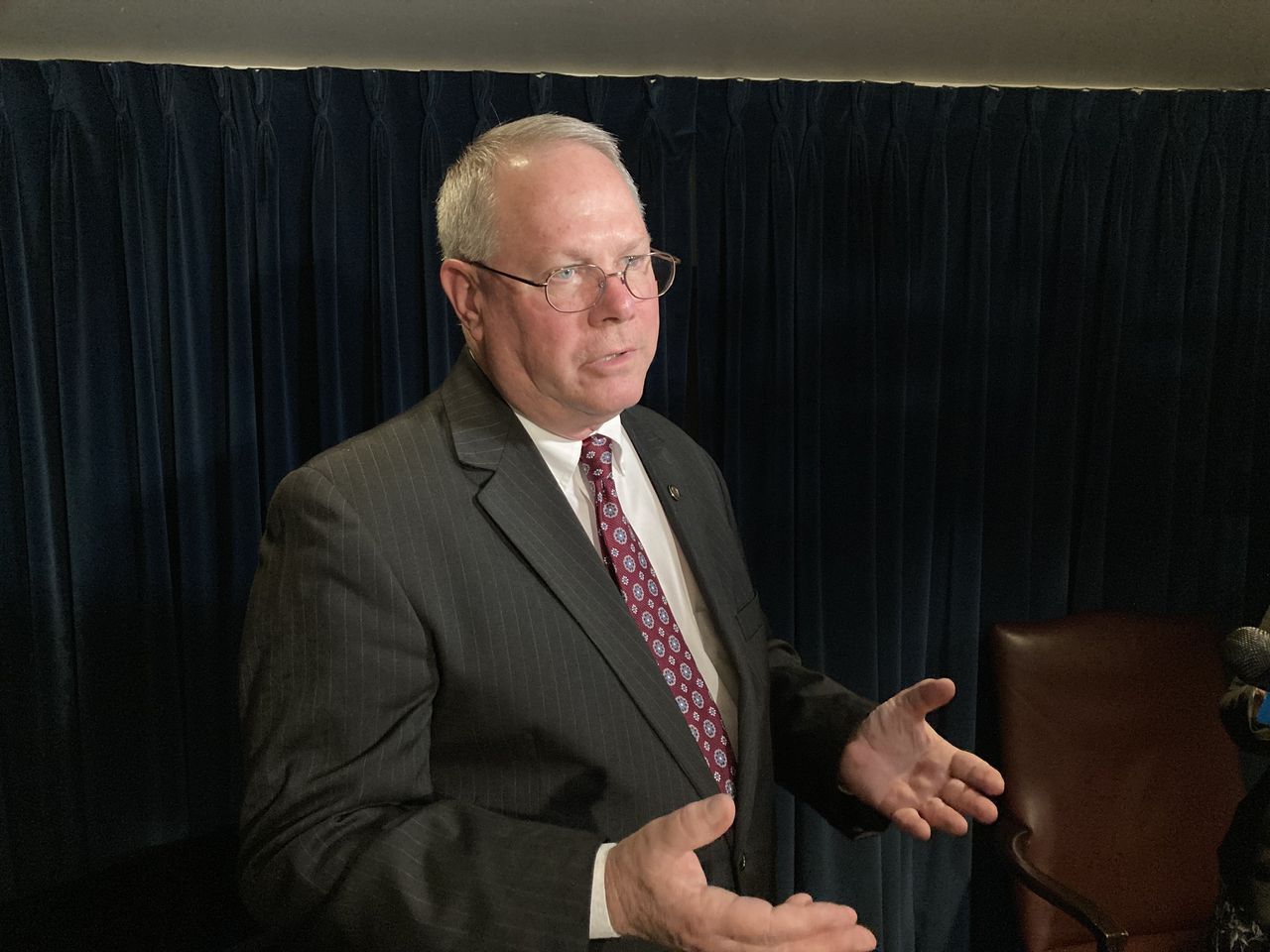

Only one Republican on the State Government Committee seemed to care. Rep. Mike Ball, R-Madison, seemed to catch his Republican colleagues off guard.

“You mean to do well, but this isn’t going to do it, because the hard work of addressing where all this started and where we can go together — we haven’t gotten there,” Ball said after calling the racial divide a spiritual problem. “And you can’t do it in an adversarial environment. You have to do it in a spirit of love, and not this side overpowering that side.”

Ball’s objections gave the bill’s opponents an unexpected momentum. Hollis spoke one more time. Whatever she had left bottled up — she pulled the cork.

“This is gonna create more problems,” Hollis said. “We already have problems and I’m tired of problems. I’m tired of racism. I’m tired of this shit.”

With the committee meeting spiraling out of control, the chairman, Chris Pringle, called for a voice vote, and the committee carried the bill over.

For most other bills in most other sessions, that would mean it was dead. But not this one.

When governing gets boring

The day after his plea to his Republican colleagues, I called Ball, who informed me the bill would be back next week.

It probably won’t surprise you to learn where Ball’s independent streak comes from. Ball is not running for reelection.

“I’m going to go play music,” he told me of his post-politics plans.

A retired highway patrolman and ABI hostage negotiator from Madison, Ball says he’s proud of what his party accomplished immediately after taking control of the Legislature in 2010, but he’s disheartened by what he sees today.

“Whether you like it or not, we did a lot of substance, meaningful things, in that first quadrennium,” Ball says.

Those changes included ethics reforms and an education trust fund policy called the rolling reserve which has effectively ended sudden job cuts due to proration in public schools.

“Once you get your initial things done, then you got to govern and that’s boring,” he says. “Republicans, we keep trying to gin up the base when the base doesn’t need ginning up.”

That’s what the CRT bill is, he says.

When I ask him why the partisan division in the Legislature has become so raw, Ball brings up a point other lawmakers, Democrats and Republicans, have shared with me — the number of Republican lawmakers who can remember what it was like to be in the legislative minority is dwindling.

As that number dwindles, the hubris of the new generation of Republicans grows.

“If a Democrat would’ve introduced that same bill, but we were in the minority, we would have called them the thought police,” Ball says.

Ball let me know he would not be there for the next committee meeting. It was clear what his Republican colleagues would do.

“When the train is coming down the tracks, ain’t no need standing there to get run over,” he says.

And the train was moving fast.

The State Government Committee met again the following Tuesday, just as Ball said. Only two Black lawmakers, including Hollis, made it to the committee room before the chairman called the members to order.

From roll call to adjournment, the meeting lasted less than 60 seconds. HB312 received a favorable report on a voice vote, over the objections of Rep. Hollis and Rep. Kelvin Lawrence, D-Hayneville.

“We discussed this in two other meetings,” Rep. Pringle, the committee chairman, said when the lawmakers demanded to know why they couldn’t speak.

Rep. Rogers walked into the meeting two minutes late, holding amendments in his hand.

“It’s over already?” he asked.

He didn’t get the time he’d been promised to speak.

Kay Ivey’s short memory

In 2019, Kay Ivey needed a Black friend.

An archivist at Auburn University discovered a 1967 interview with Ivey and her ex-husband. In the interview, Ivey described how, when she was a student at the university, she had participated in a skit called “Cigar Butts.”

In blackface.

The recording proved a rumor Ivey had denied only a year before when running for election. Ivey claimed she hadn’t lied, but rather hadn’t remembered it.

In an attempt to get ahead of the story, her chief of staff reached out to Black lawmakers first, told them what was coming and asked their forgiveness. In a public statement, she promised to do better in the future.

“While we have come a long way, we still have a long way to go, specifically in the area of racial tolerance and mutual respect,” Ivey said in a video published online. “I assure each of you that I will continue exhausting every effort to meet the unmet needs of this state.”

Some Black lawmakers, including Smitherman, accepted her apology. Others, including Rogers and Rep. Juandalynn Givan, D-Birmingham, said the governor should resign.

Regardless, Ivey stayed in office, and two years later, she was campaigning against CRT.

In a quote often repeated, the Republican political strategist Lee Atwater once traced the history of Southern white politicians using race to their advantage — from shouting the n-word on the stump to more abstract policy positions like tax cuts.

“Now, you’re talking about cutting taxes, and all these things you’re talking about are totally economic things and a byproduct of them is Blacks get hurt worse than whites,” he said.

Curiously, Atwater intended that off-the-record confession, published after his death, as a defense of the GOP’s “Southern strategy.” By moving further and further into abstraction, he argued, the party would eventually migrate so far from race that it wouldn’t matter anymore. Economic issues would take the front seat, he said.

Only it doesn’t seem to be working out that way.

From laws to protect Confederate monuments to anti-CRT bills, Alabama is regressing — away from the abstract and back toward the overt.

America, too.

And when a governor goes from promising to work harder for racial tolerance to ignoring the concerns of Black lawmakers and Black school board members, you can begin to see why lawmakers, such as Hollis, have grown so tired.

For Black Alabamians, Alabama history is a series of broken promises, and it’s only rational to be concerned that hard-won gains are always at risk of being lost.

History is not, as it’s sometimes taught, a slow-but-steady progression from the imperfect toward the more perfect, but a series of leaps forward among stumbles backward.

We’re stumbling again.

And this time, history itself is at stake.

Floor fight

When HB312 reached the floor of the Alabama House, Rep. Givan of Birmingham quizzed the Republican sponsor on what history he wanted to protect.

“Are you familiar with the Middle Passage?” she asked Rep. Oliver.

“I’m sorry?” he said.

“Are you familiar with the Middle Passage?” she repeated.

“From 1619, maybe?” asked Oliver, at a loss for what she was asking.

“I just asked you if you were familiar with the Middle Passage,” she said.

“No, ma’am,” Oliver conceded.

As many as 2 million Africans, at least, are believed to have died crossing the Atlantic on slave ships bound for the Americas, but when asked about it, Oliver grasped instead for the title of the 1619 Project — The New York Times project led by Pulitzer winner Nikole Hannah-Jones that has also animated so many CRT opponents.

Under later questioning from England, Oliver denied that HB312 was an anti-CRT bill but he left the door open for it banning CRT. England asked which it was.

“It’s not a critical race theory bill. It’s a divisive language bill,” Oliver said. “Critical race theory could certainly be included in the things that we would try to address.”

“So it is?” England asked again.

“It could be,” Oliver answered.

The debate lasted for two hours, the maximum allowed under House rules. Black lawmakers lined up, one after another, to plead with white colleagues to reconsider what they were doing.

As it had in previous sessions, the tone turned personal.

“I’m realizing, when you talk to me and tell me, ‘Oh man, you’re a good guy and I like you,’ you don’t,” said Rep. Daniels, the House minority leader.

The bill would change how he saw everyone in the chamber who voted for it, he warned.

Daniels’ argument became a refrain for the Democrats, who began telling their Republican colleagues directly that HB312 was a personal attack. Rogers called it a knife at his throat and England decried how many of his white colleagues had called him “articulate” as some sort of compliment.

“You can’t tell me these things and believe them but then not want to talk about what created me or how I got here or why I think the way that I think,” England said. “It really bothers me to know that we are debating a piece of legislation and passing a law to try to protect the sensibilities of white Americans, because this is not about anything else but that.”

As he had in committee, Ball alone crossed the aisle. While being empathetic toward his Republican colleagues’ intentions, he warned that the bill would backfire and inflame divisions.

“A lot of the problems that we are facing in our country and in our state — these are spiritual problems,” Ball said. “And you can’t pass a law that’s going to fix these spiritual problems.”

Black lawmakers shouted “Preach!” and “Amen!” to their new ally. But seconds later, House Speaker Mac McCutcheon, R-Huntsville, called for the vote.

But for three votes, it split down party lines.

Ball voted against.

But there were other curious departures from the expected split. Speaker McCutcheon voted “no,” as well. Rep. Joe Faust, R-Fairhope, and Rep. Allen Farley, R- McCalla, did too.

As the Republicans moved to the next bill on the calendar — to place new restrictions on absentee voting — state Rep. Mary Moore, D-Birmingham, sang “Ain’t No One Going to Turn Me Around” over the sponsor’s opening remarks, seemingly explaining the bill’s intent.

Other Democrats met with reporters in the small media area near the entrance of the House chambers.

“They talk about standing strong for Alabama, but goddammit, they’re standing wrong for Alabama,” Daniels said.

As he spoke, the House clerk reported small but significant changes to the HB312 vote count.

Speaker McCutcheon had intended to vote “yes,” the clerk reported.

Faust, too.

That glimmer of independence minutes before —it had been mostly a clerical error. Only Ball and Farley had crossed party lines.

Regardless, the legislation would go to the Senate, where a similar anti-CRT bill had already passed out of committee.

As Ball said, the train was speeding down the tracks, no matter who tried to step in its way.

To England, the fast-moving bill is not only about Alabama history, but about controlling its future. In Alabama, he said, we run from things that provoke thought and we shun those who take a different view of history than the one approved by the state.

“It is designed to socially engineer a particular person, and if you can’t get along with it, you don’t have a place here,” England said of the bill. “And if you can’t accept what the history that we want to give you is, you don’t have a place here, you don’t belong here, you’re not valued like the folks in charge.”

Without confronting the past’s impact on the present, Alabama would never grow, he warned.

“This legislation,” he said, “will continue to allow the dead to bury the living in the state for eternity.”