By Wayne Campbell

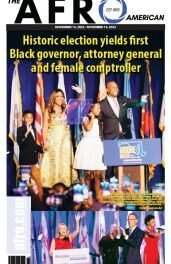

“Cant no man play like me.”

– Rosetta Tharpe

History is often unkind to people of color. To a large extent, racism can be identified as the main factor behind the erasure of a great portion of our rich and resilient history. Women of color have had to face institutional domains of separation in patriarchy and racism, which, when combined, attempted to make African-American women invisible.

One of the megastars of gospel music was Rosetta Nubin Tharpe. She was arguably the first gospel performer to record for a major record label, Decca, and an early crossover from gospel to secular music. Tharpe can be considered a feminist, as she entered and dominated—for a time—a male, White male-dominated space. She was also a social activist, given that the peak of her career intersected with the civil rights movements of the 1950s to 1960s.

Rosetta Tharpe was born in Cotton Plant, Ark., on March 20, 1915, to Katie Bell Nubin Atkins, an evangelist, singer and mandolin player for the Church of God in Christ. Her father was Willis Atkins. She went by the first names Rosa, Rosie Etta and Rosabell and used both her father’s last name and her mother’s maiden name, Nubin.

She began performing at age four, playing guitar and singing “Jesus Is on the Main Line.” By age six, she appeared regularly with her mother, performing a mix of gospel and secular music styles that would eventually make her famous. Her musical background was born in the gospel music of the Black church of the South. As a youth, she could sing, stay on pitch and hold a melody. Her vocal qualities, however, paled beside her abilities on the guitar. She played individual tones, melodies and riffs instead of just strumming chords. This talent was all the more remarkable because, at the time, few African-American women played guitar.

Tharpe is recognized as the “Godmother of Rock and Roll.” She was there before Elvis Presley, Little Richard and Johnny Cash and should be acknowledged for her work and worth to the music industry– particularly in the development of rock and roll.

It should come as no surprise that Tharpe’s chosen path was a career in music. She was always surrounded by music growing up.

By the mid-1920s, Tharpe and her mother settled in Chicago, where they continued performing spiritual music. As Tharpe grew up, she began fusing Delta blues, New Orleans jazz and gospel music into what would become her signature style.

Although Tharpe’s distinctive voice and unconventional style attracted numerous fans, it was unusual to have female guitarists who pursued both gospel and secular genres of music—especially a woman of color in the 1930s.

Without a doubt, Tharpe was determined, and her determination paid off. By 1938, she had joined the Cotton Club Revue, a New York City club that became especially notable during the Prohibition era. She was only 23 at the time, a feat amplified when she scored her first single, “Rock Me,” a gospel and rock and roll fusion, along with three other gospel songs: “My Man and I,” “That’s All,” and “Lonesome Road.”

Was Tharpe a trailblazer? Yes, she was. Tharpe’s lyrics unabashedly experimented with openness about love and sexuality, an approach that left her gospel audience flabbergasted.

She collaborated with heavy-hitting artists of the time, such as Duke Ellington and the Dixie Hummingbirds. In 1941, she began traveling widely with the Lucky Millinder Orchestra, a notable swing band, and recorded “I Want a Tall Skinny Papa.” She even teamed up with the Jordanaires, an all-White male group, and began performing for mixed audiences.

Despite her fame, institutional racism in the mid-1940s was still rampant. On tour, all restaurants and hotels were segregated. Tharpe slept on buses. She went to the back of restaurants to pick up food because they wouldn’t let her in.

Yet the spirit in her music never broke. She gained celebrity status and even became a legend among Black soldiers fighting in World War II. After the war, Tharpe worked with Sammy Price and produced a famous spiritual single, “Strange Things Happening Everyday,” with Decca Records. Tharpe began touring again in 1957, attracting a new generation of fans with her unique voice and delivery. She continued touring in Europe practically until the end of her life. Her last known recording was in 1970 in Copenhagen.

Legacy lives

Tharpe was a pioneer in her guitar technique; she was among the first popular recording artists to use heavy distortion on her electric guitar, paving the way for the rise of electric blues. Her guitar-playing technique had a profound influence on the development of British blues in the 1960s.

In 1992, when Johnny Cash was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, he mentioned Tharpe as an early influence on him. He remembered buying records as a youngster, saying, “Some of the earlier songs I wrote were influenced by people like Sister Rosetta Tharpe.”

Tharpe was historically overlooked in rock and roll history. However, in 2018, she was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

Tharpe paved the way for other African-American women and even White men, such as Elvis Presley, who is regarded as the “King of Rock and Roll.”

Rosetta Tharpe was both a pioneer and an inspiration.

She died on Oct. 9, 1973, at age 58.

The post Celebrating Women’s History Month: The legacy of sister Rosetta Tharpe, a pioneer in gospel and rock appeared first on AFRO American Newspapers.