By Kelly Kazek

On Nov. 15, 1989, Huntsville resident Scott Gilbert, then 24, was taking a quick break with coworkers to get a soft drink at Riley’s Food Store on Queensbury Drive, across from Golbro Jewelers department store.

“We walked out and I saw Golbro explode,” Scott recalled in a 2010 interview for the book “A History of Alabama’s Deadliest Tornadoes.”

“We thought a bomb went off at first,” Scott said. “The smoke was so black. We didn’t see a lot of wind yet all these cars came tumbling by. A huge dumpster container behind Riley’s started spinning in a circle and shot up into the air and hovered above us. We all started running.”

The tornado quickly overtook them. “When that first wind came over, you could see clear up into a short, squatty tornado,” Gilbert said. “It was wide at the base. Then there were five or ten seconds when you were in the center of it. You could see it all around you. The noise was indescribable. Our ears were popping so bad from the pressure.”

Scott was struck in his shoulder blade by a cinder block and he required 400 stitches to close the wound. But he was one of the lucky ones.

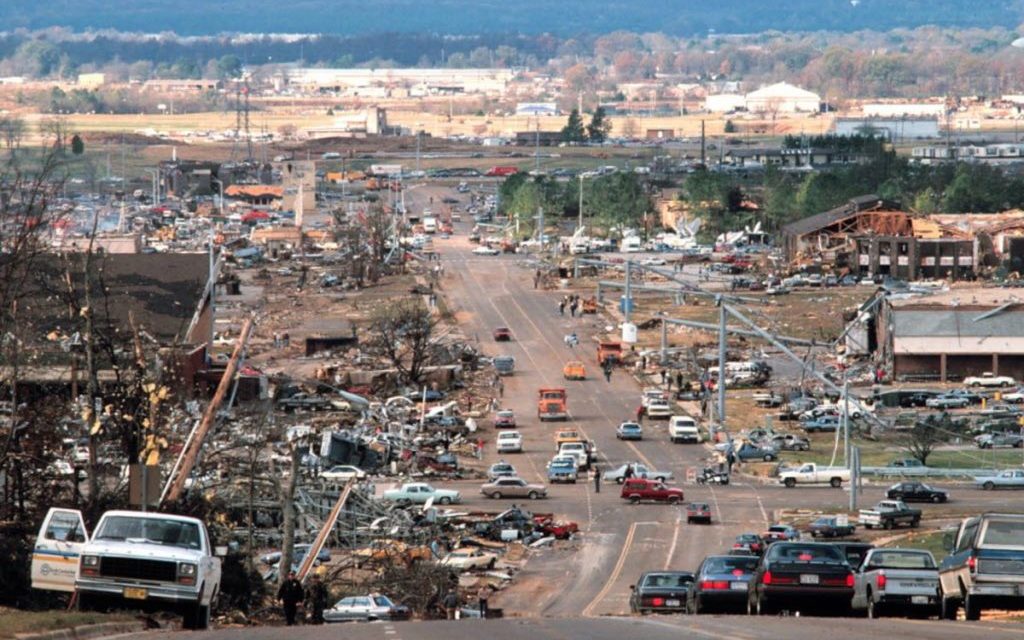

Before the F4 tornado had made its way through south Huntsville, 21 people would be dead, 259 homes completely destroyed and hundreds of others damaged, 80 business wiped out and two schools demolished, according to reports at the time from The Huntsville TimesandThe Huntsville News. In addition, the storm caused $1.9 million in damages – about $4.8 million today – to public utilities.

Black Wednesday

In 1989, Huntsville was growing fast, on its way to being named Alabama’s largest city in 2023. But 35 years ago, the city ranked as fourth largest with about 160,000 residents.

Residents of the Rocket City, a hub of technology and home of NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center and Redstone Arsenal, were familiar with severe weather. Fifteen years before, an F3 twister — one of 148 twisters in the April 3, 1974, tornado outbreak — had killed two people and destroyed Parkway City, then a shopping center and later rebuilt as a mall, as well as about 1,000 other structures.

In 1989, people knew to heed weather sirens and to listen to radio and television reports about pending dangerous storms. On Nov. 15, though, modern technology didn’t help the residents of Huntsville. That day, meteorologists issued a severe thunderstorm warning and a tornado watch but, when it came, the devastating twister was still a surprise.

Before it struck, scientists monitoring the equipment at the Weather Service Office not far from Airport Road saw no indication of tornado rotation on radar. It wasn’t until a tornado was spotted on the ground at about 4:35 p.m. that sirens were activated and by then, it was too late: Rush hour had begun. Twelve of the 21 people killed died while in their cars.

The day became known as Black Wednesday.

The tornado, which reached wind speeds of about 250 mph, first touched down on Redstone Arsenal and then struck Huntsville new garbage incinerator, causing $1 million in damage there. It then crossed the property of the old airport, adjacent to the municipal golf course, before hitting Huntsville Police Academy, and two officers were injured. When it crossed Memorial Parkway at Airport Road, dozens of cars were at the busy intersection. Nineteen of the 21 deaths occurred between the intersection of Airport Road and South Memorial Parkway and the intersection of Airport and Whitesburg.

The storm then moved up Garth Mountain and struck Jones Valley Elementary School, where 37 students and five teachers were at an after-school daycare program. The children were taken to the school’s basement for shelter and painters working at the site helped shield children with their bodies, saving lives.

Before it finally dissipated, the tornado hit Jones Valley subdivision, moved up Huntsville Mountain, and crossed Red Mountain before ending at a small creek.

Aftermath

When the storm was over, Scott Gilbert discovered his Ford F-150 truck was overturned in the middle of Airport Road. All four tires were flat and when he took the truck to be repaired, workers discovered the insides of the tires were covered in pink insulation. Gilbert also said it took four days to scrub the asphalt from his skin because it had been blown so hard, and that his pants pockets were filled with gravel.

In another odd moment after the storm, Mona and Fred Keith thought their Jones Valley home had not sustained major damage until they went to get blankets from a coat closet to give to storm victims. That’s when they found a hole in the roof and a pile of bricks inside. The bricks had been blown there from the heavily damaged Jones Valley Elementary School. The Keiths also found a desk from the school lodged in a magnolia tree in their yard.

At Holy Spirit Catholic Church, three pillars with the words “Faith,” “Hope,” and “Love” remained standing in the ruined sanctuary.

One of the oft-repeated stories from the 1989 storm occurred when Jeanette Johnson was rushing to get inside her home on Toney Drive. She was trying desperately to get a key in front door’s lock when the twister hit. She pressed her body tight against the door and tried to shield the front of her body. Suddenly, she was pummeled by flying debris.

When it was over, she saw much of her house was gone but the front door was still standing. On its front was a clear silhouette of Jeanette’s body. It was white where her body had been huddled but the remainder of the door was coated by shards of glass, wood and other debris. Jeanette credited her London Fog all-weather coat for her lack of injuries. When her account was reported in The Huntsville Times, the president of London Fog sent Jeanette a new coat.

Steve Owens of Madison recalled in a 2014 AL.com article that he was working at Golbro Jewelers when the tornado struck. “I cleaned glass out of my ears for two weeks,” he said, “and would become terrified when I heard the slightest wind noise. … Nov. 15, 1989 changed my life, made me value life more.”