By William Thornton

Makendy Durerger came to the U.S. in April, settling in Albertville and finding a job with Pilgrim’s Pride.

Marshall County, he said, is far different from Léogâne on the island of Haiti.

“There were shootings, gangs,” he said, through an interpreter. “You’re sleeping with your kids, trying to keep them safe. You’re scared.”

Durerger is among thousands of Haitians who came to the U.S. this year to escape the unrest in the nation of more than 11 million east of Cuba in the Caribbean.

Durerger came with his two children but had to leave his wife behind. He is currently working through the diplomatic process to bring her here.

Jolken Plaisir, 29, came in March and found a job at an auto supply plant in Cullman. Living in Mirebalais, he dreamed of coming to America in hopes of finding a better life.

“At this moment, there is no life in Haiti,” he said through an interpreter. “There is no future for kids. No food. It is a chaotic way of life.”

The community in August found itself facing suspicion and what Albertville city officials called “baseless accusations, and hurtful rhetoric” when photographs of Haitian workers in charter buses were shared on Facebook.

Some questioned what purpose the buses served, who was on them, and where the people onboard were coming from.

Pilgrim’s Pride later issued statements saying it had chartered the buses for employees to and from its Russellville plant. The company then said it would no longer use charters.

But the photos sparked discussion centered around recent Haitian immigration and its impact on the city in a series of community meetings.

Some concerns centered on the toll a growing population put on public resources, with some residents calling for a rational discussion “without all the racial slurs” and angry rhetoric.

One speaker, however, said Haitians “have smells to them. They’re not like us. They’re not here to be Americanized.”

The photos also led to the formation of a non-profit group that at least one Haitian community leader said was a positive development.

Jeff Lamour is a businessman who graduated from Albertville High in 2017. While a student, he participated in the State Indoor Track and Field Championship, and holds several school records in the 100-meter and 60-meter dash.

Lamour said prior to the recent controversy, he felt most Albertville residents had a positive view of the Haitian community.

“People have the right to be concerned,” Lamour said.

“If somebody moved in my neighborhood, you could be anybody, If somebody was walking on my lawn, I would want to know why is this person walking on my lawn. There are peoples that’s racist, without a doubt.

“Not only white people, but Black people, Hispanic people. There are people who feel more entitled than others. They feel like this is their country. But at the same time, it’s not about race. Race has nothing to do with it.”

‘Better things to come’

Alabama has 2,569 Haitian residents, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

Albertville has had a Haitian population going back almost 15 years, but longtime members of the community estimate several thousand have been added just this year. The reasons are many.

Haiti in the last 20 years has been racked by government corruption, a series of devastating earthquakes and hurricanes, and internal turmoil.

A wave of unrest on the island earlier this year began when armed paramilitary gangs seized the capital at Port-au-Prince, emptied prisons and forcing out the government. Almost 1,400 people were wounded or killed from April through June, a quarter of them women or children, according to the U.N.

Rapes were common. Vigilante groups began reprisals, leading to more bloodshed. Hundreds of thousands of people have fled to rural areas on the island, straining resources, according to The Washington Post.

In June, the Biden Administration announced temporary protected status for Haitian immigrants, which was expected to keep about 309,000 Haitians living in the U.S. from deportation, according to the Department of Homeland Security.

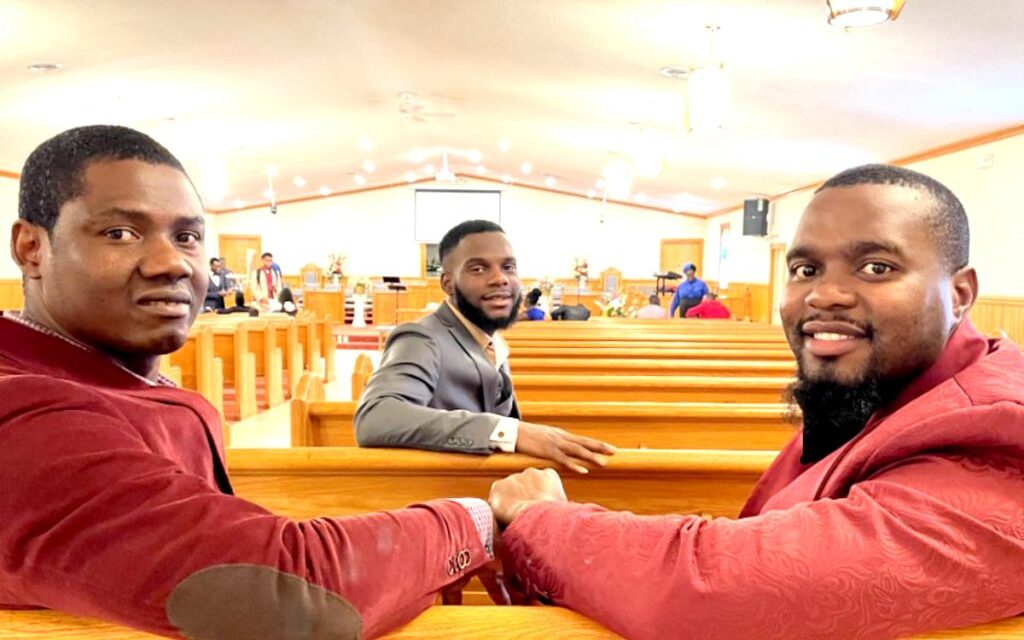

On a Sunday morning, one vibrant part of Alabama’s Haitian community could be seen at Eglise Porte Etroite, which bills itself as the first Haitian church in Marshall County.

Drive by the brick sanctuary on Rose Road and you’ll see cars extending past the parking lot, squeezed into neat rows on the grass.

Inside, more than 200 people in brightly colored suits and dresses gather for worship services in Creole that last sometimes three hours. Mothers stand by the doors holding unruly toddlers and sway as hymns play with a Caribbean rhythm.

Daniel Emmanuel-Laguerre, 24, of Guntersville, has lived in Alabama since 2011 when there were only a handful of Haitians here, he said.

“I had to learn English very fast,” he said. “My family came for a better living, for better opportunity.”

He is earning a degree in logistics and calls the church his real home. On Saturday, people came for a prayer service that lasted 12 hours, he said. Those who attended prayed for “better things to come.”

‘People are getting rich’

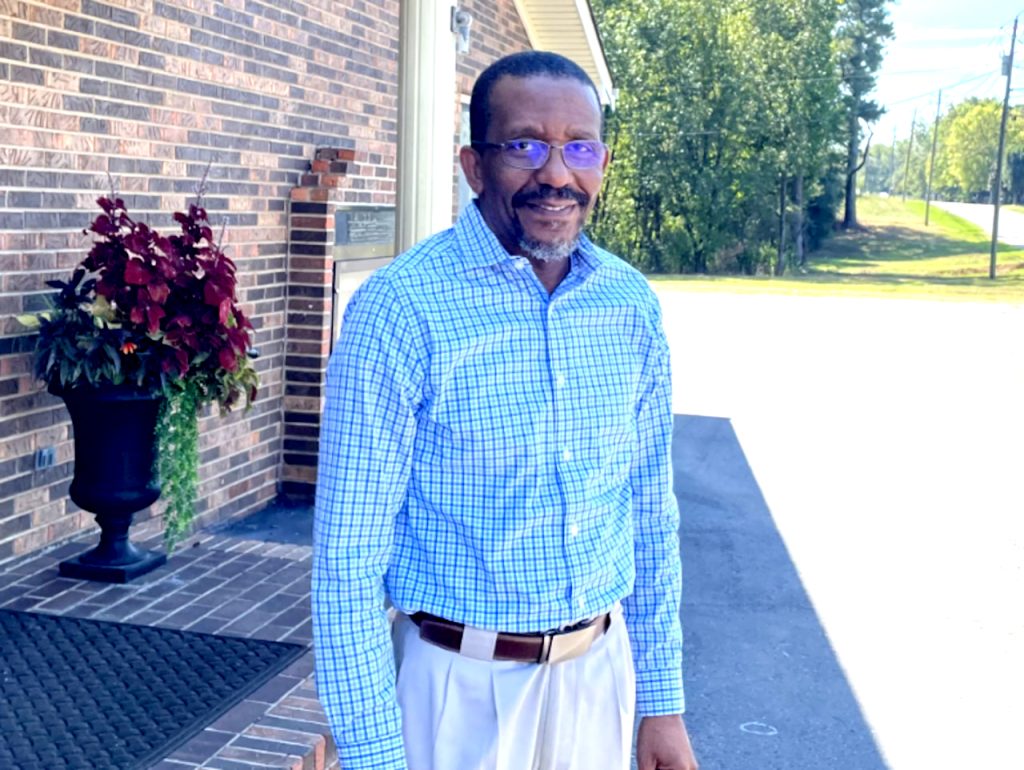

Johny Pierre-Charles, 54, the pastor of Eglise Porte Etroite, has been in the U.S. since 2006 and formed the church 14 years ago with less than 10 people. He has a wife and three children and also serves as a chaplain for Pilgrim’s. Before that, he was a police investigator in Port-au-Prince.

Pierre-Charles said he also feels the issue in Albertville has not been about race, as some of the problems are cultural misunderstandings. He felt welcome when his family first came to Alabama.

“I would never say it’s racist here,” he said. “Alabama is the best place to live. It’s the truth.”

He chose to live in Alabama instead of New York City, he said, which has a Haitian community of more than 150,000.

“We need to let some Americans know that, if there is a problem, there’s a better way to fix it,” Pierre-Charles said.

“The best way is love, and to reeducate Americans and reeducate Haitians. I know it’s not easy when you’re not used to our culture.”

He said the biggest needs of arriving Haitians, besides education in English, is housing. Most came because of jobs at poultry processing plants. The biggest need for everyone – Haitians and Americans, he said – is patience.

Lamour said he worries that many newly arriving Haitians are being exploited by being forced to pay high rents for substandard housing.

“You go to a house with no plumbing, no air conditioning, that’s run down, and then you take a Haitian newcomer, and you put them inside that house, and you charge them $2,000 a month, and if they report you, you tell them you’re going to kick them out. We’re dealing with situations like that.”

He also feels U.S. policy which allows up to 30,000 people a month from Haiti and three other countries to immigrate for work is being abused.

Migrants must have a financial sponsor in the U.S. who can fly them into an airport at their own expense.

The program was briefly suspended for suspected fraud, but the Biden Administration reinstated it last month, announcing a series of changes to improve vetting.

Lamour said some migrants are being trafficked for labor – charged exorbitant fees to come to the U.S., and after finding a job, most of their pay going toward reimbursement.

“People are getting rich off of this thing, and the Haitian people aren’t seeing any of the money,” he said. “You’ve got guys who contract with those companies who can hire somebody for barely nothing.”

‘The federal government is responsible for this’

During the series of community meetings with longtime residents of Albertville, audience members shared rumors of high crime from Haitian gangs and concerns that already overcrowded schools would be engulfed by children from families unwilling to assimilate.

However, Marshall County Sheriff Phil Sims said he is unaware of any uptick in crime in the county associated with Haitian immigration. Robin Lathan, a spokesperson for the city of Albertville, said the same holds true there.

“Looking at year (by) year data, to include arrest reports, the nature of incoming emergency calls, and demographic information, there is no evidence to suggest, one, that crime in Albertville has increased, or, two, that it has increased as a result of Haitian immigration,” Lathan said in a statement.

And while there are more Haitians entering schools, there is more to the story.

At Albertville City Schools, 111 Haitian students have enrolled in the city since January, with 66 of that number coming since the summer, Superintendent Bart Reeves said.

Those numbers are not significantly different from previous years, he said.

For example, 60% to 70% of the approximately 500 kindergarten students that enter the system each year are the children of Latino migrant workers, though they may be first, second or even third generation living in the U.S.

In total, Haitians account for about 2% of the total student population of more than 5,800.

The system does have translators on staff, not just for Creole or French, but the more than 10 languages represented in the entire district.

Albertville schools receive almost $530 per English learner from the state, but only $89 from the federal government.

Eventually, some students become proficient in English and no longer require extra instruction. But Reeves said schools in Albertville will eventually need expansion, and more bilingual teachers, counselors and aides.

To deal with all the current needs, Reeves said, the system could easily hire 10 teachers’ aides in kindergarten, first and second grade, if the funding was available.

“The federal government is responsible for this,” Reeves said. “Since they are responsible, how come they’re not helping these smaller cities with the influx of immigration challenges that we receive?”

‘If they wanted to fix it’

Many in the Haitian community say they feel grateful for the reception they’ve received.

Plaisir and Durerger said their experiences working in Alabama have been positive, despite the language barrier.

They both said they are treated well, though sometimes they have to communicate through sign language. Their lives are much better in Alabama, they say, than if they stayed in Haiti.

But they expect other Haitians to follow them, and they do not anticipate going back home unless the unrest is quelled.

A U.N.-backed security force, funded largely by the United States, has been organized to help stabilize the country.

But elections are planned for more than a year from now in Haiti. Pierre-Charles said a smart investment for Americans would be to “build houses” to accommodate more immigrants.

“All the good Haitians are trying to leave,” Durerger said.

But Lamour, Pierre-Charles and others say that if America is concerned about increasing numbers of Haitian immigrants, it could easily restore order by intervening on the island.

American troops have been stationed in Haiti several times to quell unrest or render humanitarian aid, most recently when President Bill Clinton ordered more than 20,000 troops there in 1994.

Much of the current chaos, Lamour said, can be seen as a result of American policy.

“If they sent 10 American soldiers to Haiti, it would be over,” Pierre-Charles said. “The situation in Haiti can be fixed in one day, if they wanted to fix it.”