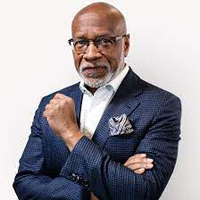

By Roy S. Johnson, member of the National Association of Black Journalists’ Hall of Fame, an Edward R. Murrow Award winner, and a Pulitzer Prize finalist for commentary

This is an opinion column.

The Rev. Anson West was absolutely right—though I’ll swear on a stack of Bibles he didn’t see this coming.

West was among a clutter of faith-filled men striving in late 1917 to secure the future of two struggling Alabama Methodist colleges. One was the mostly male Southern University in Greensboro, Alabama; the other was Birmingham College, which opened just before the turn of the 20th century with a faculty of four and 77 students. The men decided to merge the two wheezing institutions and settle the new entity in the burgeoning metropolis that was fast becoming the bright sun in the emerging steel-making universe.

West gazed upon almost 200 acres on a hill just west of the city’s core and was said to declare: “God created that hill for the site of a college.”

He was right—a Black college.

The Rev. West, of course, did not mean a Black college. Far from it. His declaration preceded the birth of Birmingham-Southern College, which opened on that hill in the spring of 1918 and stood proudly for almost 106 years, educating generations in the liberal arts. It stood proudly until the gates of the iron fence that guarded the institution from the world outside were padlocked on May 31 after too many years of financial failings.

Yet the Rev. West’s prescient prophesy—unintended as it may have been—still holds, it seems. As of now that hill God created on Birmingham’s west side looks highly likely to remain the site of a college. A historically Black college.

Just as it should.

Anything—and everything—can certainly happen before a deal is done. Though as of this writing Miles College, now in Fairfield just outside city limits, and Alabama A&M, based in Huntsville, are ensconced in a bit of a bidding battle for the 192-acre property.

Miles looks to be a slight favorite, at least at the moment. As reported Monday by the Birmingham Times, and confirmed by AL.com, the institution signed a letter of intent to begin negotiations to buy BSC.

“The letter was signed on Juneteenth,” confirmed Miles spokesperson Mya Jolly.

A letter of intent typically creates a window of exclusivity for the potential buyer to reach an agreement, during which time the seller cannot engage in negotiations with any other party.

That wasn’t good news for folks at Alabama A&M, who’ve been openly effusive in courting that hill for a Birmingham extension of its Huntsville campus. Indeed just a day after we learned of Miles’ letter of intent, A&M said in early June it made a $65.5 million offer for BSC—$35.5 million in cash and $30 million in “maintenance,” said Shannon Reeves, AAMU’s VP of government relations and external affairs.

Reeves said the offer was a $13.5 million increase from A&M’s initial $52 million offer ($22 million cash, $30 million maintenance) made on May 1.

“We see this increase as a reasonable increase that will clear all BSC outstanding debt,” Reeves told me in a text message. “As a public institution, we must be good stewards of public funds. Therefore, we hope BSC Trustees will accept our offer.”

If I’m BSC President Daniel Coleman, like any seller, I’d only count the cash going into my pocket as the “offer”—but I digress.

Miles President Bobbie Knight has not commented at all on her efforts to move into Birmingham, so there’s no indication of where Miles and BSC are in negotiations. If they’re anywhere north of $40 million, that’s still the bet.

It’s actually a bit of a shame that two HBCUs are wallet-wrestling one another over the prime property. Bidding typically only drives the price up, which advantages only the seller, not the bidders.

It was previously reported that Knight is seeking to create an HBCU consortium campus, featuring programs planted and operated by various HBCUs from across the state. It’s an intriguing and innovative notion, giving Alabama HBCUs visibility and proximity to high school students throughout the area.

Those HBCUs would presumably lease space on a property attractive to students seeking to matriculate in Birmingham, within a MAX bus ride of myriad internship and career opportunities with businesses and municipalities in the region. Which may be particularly attractive for graduates of Birmingham City and other area school districts desiring to remain close to home.

Call it a united Negro college force.

A&M, however, does not want to play in that sandbox. Reeves reiterated this week: “…AAMU’s commitment to maintain the entire BSC property as an academic facility focused solely on higher education. Furthermore, we are committed to attempting to bring economic development and increased property value to the surrounding neighborhoods.

Now, it might be left outside the gates.

BSC’s slow death hurt many and scared even more. The possibility that its already-needy remains might deteriorate further for years into deep disrepair (See: Carraway Hospital) was a nightmare for city officials. And nearby residents feared the property would into the hands of an evil developer from Gentrification Inc., and severely alter the character of the surrounding neighborhood.

Soon, those fears may be eased.

There are tons of unanswered questions, of course. Maybe foremost: How will either Miles or Alabama A&M afford to buy BSC? I presume financial types with more access than I to their piggy banks (and flush friends) have already thought that through. It would be a travesty if an HBCU bought the place and found itself in a few years as financially strained as the previous occupant.

I’ll dismiss that negative thought and celebrate the possibility of an HBCU (whichever one it may be) on that hill.

Just as God created it to be.

Just as it should be.