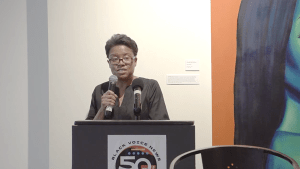

Denisha Williams and Reginald Williams

Special to the AFRO

On Valentine’s Day, 2024, I was diagnosed with cancer.

“You have sarcoma of the bone, and it’s spread to your lungs,” my oncologist said.

Although my doctor demonstrated care with the pace at which he conveyed the disturbing news, there came a point when the sounds ran together, leaving me with the impression of Charlie Brown’s muddled “wah, wah, wah, wah.”

To put it simple: I was scared.

I was angry, and in that breathtaking moment, I wondered if I would live.

Since 2022, I’ve suffered pain primarily in my hip and knee. I’ve sought out doctors. I’ve followed their instructions– only to remain in constant pain.

I took the prescribed physical therapy. I tried dry needling, which brought some relief, but didn’t alter the frequent trips to the emergency room to get cortisol, or Toradol shots or some other medley of prescriptions that offered no sustainable relief. Acutely treating my pain took precedence over ordering exploratory testing that could recognize the cause of my pain. Had they ordered more testing, it’s possible my cancer may not have metastasized.

Having my world shaken left me connected in real-time to all the studies that showcase how America’s sick care system treats Black women—like we are expendable.

According to Health Equity Among Black Women in the United States, a Journal of Women’s Health article authored by the National Institute of Health (NIH), the health disparities experienced by Black women are the “reflection of the inequalities experienced by Black women on a host of social and economic measures.”

A study from the American Cancer Society reports that about one-third of African-American women reported experiencing racial discrimination from healthcare providers.

Black women are often unheard and made to feel like they’ve done something wrong.

My spirit usually felt burdened by my many early morning visits to emergency rooms.

For reasons unbeknownst to me, my pain grew more unbearable in the early a.m. hours. I was inundated with feelings of being a hypochondriac– I felt more concerned about being a burden to the medical staff and felt they were more concerned with getting me out of their crowded emergency room. At no time did I ever feel like the staff was authentic in helping me discover the root of my persistent pain.

NIH reported that African-Americans “are systemically undertreated for pain relative to White Americans.”

In some cases, self-advocacy can be life-saving. A lack of it enhances poor health outcomes.

While it wasn’t always easy for me to articulate with preciseness the nuances of my pain, physicians responded to my disjointed explanations with short-term medical stabilization to conclude my visit or discharge me from their busy emergency room. Within hours of receiving their short-term solution, my pain returned. It would be almost two years later, and spots on my lungs that pushed a new doctor to explore all my health challenges.

The disparity in care I have received leaves me with a feeling of despair.

As my 37th birthday approaches, I will pause my chemo treatment and begin radiation to address two lesions found on my brain during my hospitalization.

A couple of weeks later, around Mother’s Day, the chemotherapy running through my veins may save my life, but also potentially ruin my chances of becoming a mother.

I still recognize that I am blessed. However, it doesn’t soften the hurt that on Valentine’s Day, my oncologist broke my heart.

I still hear the doctor say, “Ms. Williams, you have sarcoma, and it’s spread to your lungs.”

The post Commentary: A time to fight: How one woman is using her cancer diagnosis to bring awareness to others appeared first on AFRO American Newspapers.