By Brennan Stewart,

Capital News Service

February was Black History Month, an observance meant to honor and celebrate the achievements made by African Americans throughout the history of the United States.

But reminders of the oppression that African Americans suffered are still on display in the United States Capitol, taking the form of 12 statues of figures affiliated with the Confederate States of America and post-Civil War segregation.

Indeed, visitors to the Capitol might be startled to see civil rights icon Rosa Parks just across the room from Confederate President Jefferson Davis. And the continued presence of Confederates and segregationists in statuary in a symbol of democracy amazes scholars as well.

“While the effects of having Confederate statues in Washington — much less in the nation’s capital — should be quite clear, what still surprises me years after statues started being removed is that something like this is still a possibility,” Lester Spence, professor of political science and Africana studies at Johns Hopkins University, told Capital News Service.

Many of the offending figures stand in the National Statuary Hall, located just steps from the Capitol’s iconic Rotunda. Once the meeting place of the U.S. House of Representatives, the massive semicircular room was transformed into a statue gallery in 1864. Under federal law, each state is allowed to provide no more than two statues to the collection.

By 1933, the hall became overcrowded with 65 statues making up three circular rows along the circumference. Not only did the room start to look visually unappealing but concerns also were raised about the chamber’s structural integrity.

As a result, Congress passed a law saying that one statue from each state could remain in Statuary Hall while the others would be relocated to other areas of the Capitol.

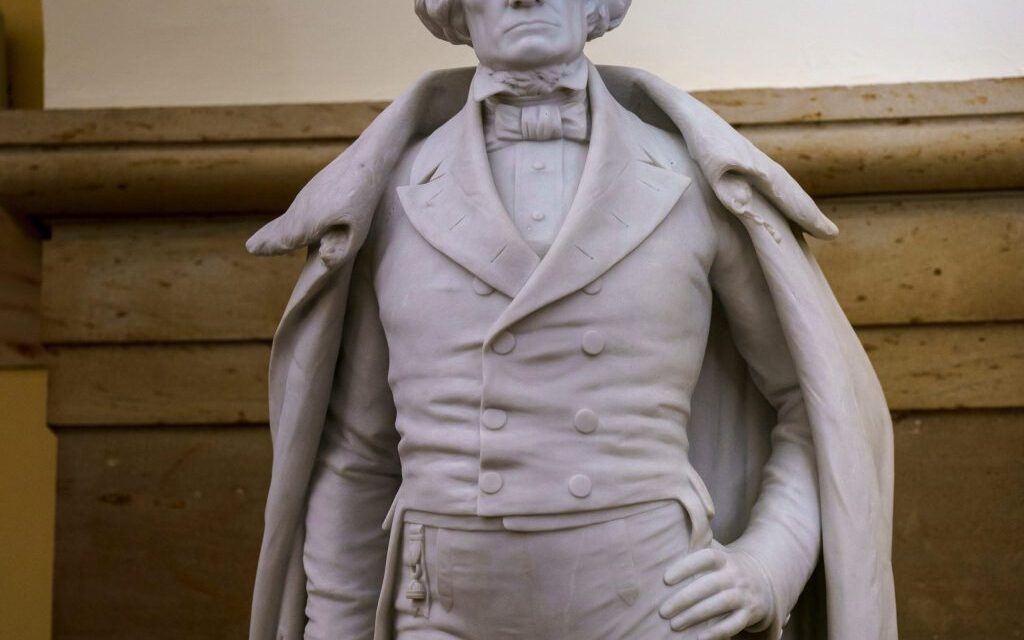

Today, five statues with Confederate ties remain in Statuary Hall, including Davis and his vice president, Alexander Stephens. Four others are located in the Capitol Visitor Center, two are in the Crypt under the Rotunda, and one more is in the Hall of Columns underneath the House chamber.

Arkansas, Georgia, Mississippi and North Carolina currently have both of their two permitted statues linked to the Confederacy or segregation, while Alabama, Louisiana, South Carolina and West Virginia each have one.

However, three of the 12 statues are facing replacement.

Then-Arkansas Gov. Asa Hutchinson signed legislation in 2019 to replace his state’s statues of Uriah Rose, a Confederate sympathizer, and James Paul Clarke, a former U.S. senator and White supremacist. They are set to be replaced with statues of civil rights activist Daisy Bates and musician Johnny Cash.

North Carolina Gov. Roy Cooper signed a formal request in 2018 for the removal of the statue depicting former Gov. Charles Aycock, who served in office from 1901 to 1905 and was a supporter of segregation. Aycock is going to be replaced by evangelist Rev. Billy Graham, but there have been several delays in getting the statue to Washington.

“When we first started the process in 2018, we were shooting for 2021 but the global pandemic and a couple of other things threw us off,” said Garrett Dimond, attorney for the North Carolina General Assembly. “We would like to do (the unveiling) in the spring, but that’s up to Congress to schedule the ceremony.”

For a new statue to be displayed in the Capitol, it must first go through several stages of approval at both the state and federal levels, Dimond explained. The process starts with the governor, who submits the bill for a new statue to the Joint Committee on the Library of Congress.

“The next step is actually going through the artist selection process, putting together a full-sized clay model and then doing the complete stack— so there’s a lot of approvals that happen with that,” Dimond said.

The Confederate Monument Removal Act was introduced to Congress in 2017 by Rep. Barbara Lee, D-California, in the wake of the “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville. Under her bill, all statues depicting individuals who willingly served in the Confederate States Army would be removed from the Statuary Hall collection within 120 days.

In February of last year, Lee reintroduced the bill with Rep. Bennie Thompson, D-Mississippi, and Sen. Cory Booker, D-New Jersey.

There has been no action so far on that legislation.

Rep. Steny Hoyer, D-Maryland, is another member of Congress who has pressed for the removal of the offending statues. Hoyer successfully passed bills twice in the House in 2020 and 2021 that would replace a bust of Supreme Court Chief Justice Roger Brooke Taney, who ruled in the 1857 Dred Scott decision that a Black man was not a citizen, with a bust of Supreme Court Associate Justice Thurgood Marshall, the first Black justice appointed to the high court.

The bill would also have removed the statues of Aycock, Clarke and Vice President John C. Calhoun, a supporter of slavery. But neither measures passed the Senate.

“We can’t change history, but we can certainly make it clear who we honor,” Hoyer said in a statement last week. “I’m proud to have led efforts to remove statues and symbols honoring Confederate and White supremacist leaders, and I lament that this is not a priority for today’s Republican House Majority.”

“I remain committed to working with Members from either party who are committed to ensuring these symbols of hate have no place in Congress,” Hoyer added.

This article was originally published by Capital News Service.