By Megan Sayles

AFRO Business Writer

msayles@afro.com

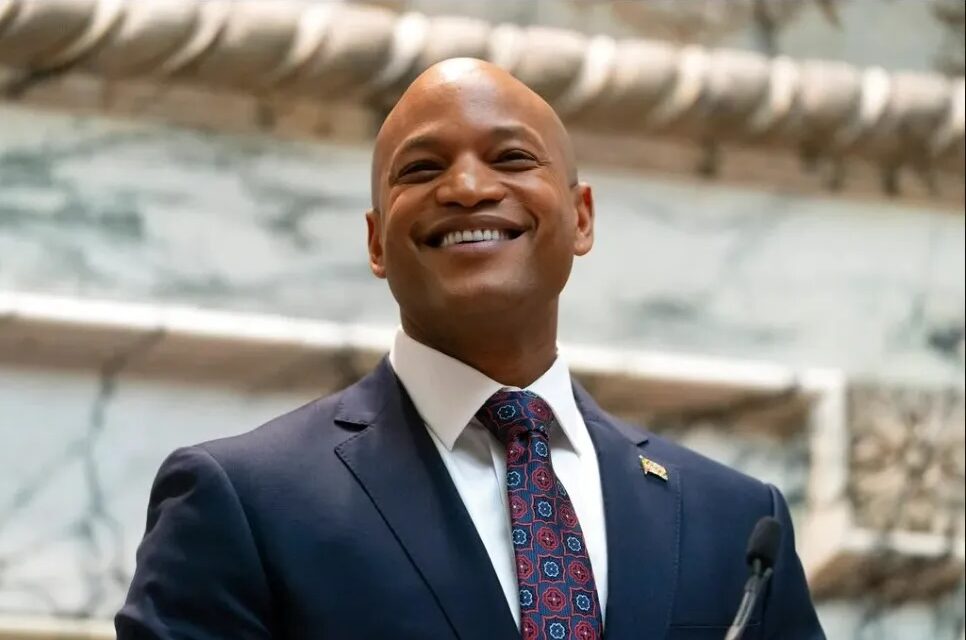

Maryland residents living in historically redlined communities may now get a new chance at homeownership, thanks to a new program announced by Gov. Wes Moore on Dec. 4.

Managed by the Maryland Department of Housing and Community Development (DHCD), Utilizing Progressive Lending Investments to Finance Transformation (UPLIFT) will tackle appraisal gaps and advance new construction and the restoration of quality affordable housing. Homeownership has long been considered a tool for wealth-building, and the program seeks to use it to close the racial wealth divide.

“Tackling the racial wealth gap is a priority of the Moore-Miller Administration. We must actively work to reverse decades of disinvestment through good policy decisions and innovative programs like this one,” said Moore in a statement. “Maryland will be a leader in these efforts, and we will continue to expand work, wages and wealth for all Maryland families.”

Redlining’s legacy of disinvestment has caused homes in certain neighborhoods to appraise for less than the cost to build them. UPLIFT will finance the difference between the appraised value and the sales price.

The program will then select developers to build, sell and rehabilitate housing in targeted neighborhoods, which will be identified using data from the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) low-income Census tract and Maryland’s Sustainable Communities.

Twenty-five percent of the homes will be earmarked for residents with incomes below the area median income. As new homes are constructed, the expectation is that UPLIFT will boost the housing markets in these communities and reduce the appraisal gaps that exist.

UPLIFT’s initial round of funding amounts to $10 million, as allocated in Maryland’s budget for fiscal year 2024. The program expects to directly finance nearly 200 units in eight to 10 projects in its first phase.

“Overall, our hope is that UPLIFT responds to two urgent, if long-delayed, priorities for Maryland. The first is to close gaps in household wealth across racial categories by elevating depressed property values in capital deficient neighborhoods, predominantly occupied by historically disadvantaged households,” DHCD Secretary Jake Day told the AFRO. “The second is to strengthen those neighborhoods so they effectively support the aspirations and well-being of those living within them.”

Photo courtesy Maryland Department of Housing and Community Development (DHCD),

The origins of redlining date back to the 1930s under President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal. At that time, the federal government established the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) and the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) to address the housing crisis engendered by the Great Depression.

The HOLC created “residential security maps” of major U.S. cities to categorize neighborhoods based on their perceived risk for mortgage loans. Hazardous or high-risk areas were shaded in red on the maps, and largely comprised Black neighborhoods. The FHA promoted the use of these maps to lenders, incorporating them in its handbook for underwriting.

“Redlining is not just the story of banks that don’t lend. It’s also the story of the way the federal government taught banks how to create security maps that they used to redline. You have this government action that helps initiate redlining,” said Lawrence T. Brown, research scientist at the Center for Urban Health Equity at Morgan State University (MSU). “You also have the appraisal system. Even though they are not engaged in lending, they’re using these maps to devalue Black property, especially in Black neighborhoods.”

Brown is the author behind “The Black Butterfly: The Harmful Politics of Race and Space in America.” In the book, he uses Baltimore as an example to examine the causes and effects of segregation and discriminatory policies, like redlining.

He coined the term “Black Butterfly” to illustrate how predominantly Black and low-income neighborhoods make up the East and West side of the city, resembling the wings of a butterfly.

“Research is continuously documenting that redlining is still taking place today nationwide,” said Brown. “Banks are at the heart of redlining, but you can see other entities engaged in it, like insurance companies. They’ll often charge more for insurance in Black neighborhoods.”

He pointed to a 2019 Urban Institute study that reported that the average loan amount per household in neighborhoods where the population is more than 85 percent African American was $68,133 but in neighborhoods where less than 50 percent of the residents are African American the amount was $160,438.

Brown thinks UPLIFT will benefit the chosen households, as they will not have to pay the difference created by appraisal gaps. However, he considered it a baby step in fixing a pervasive problem.

“If they’re only going to cover the gap in a system, where appraisers can con

“The phenomenon of redlining is so deep that $10 million won’t go very far. That’s my concern. It’s a great idea, but this should be the first baby step,” said Brown. “The appraisal system itself needs to be changed. If they’re only going to cover the gap in a system, where appraisers can continually devalue and undervalue homes in Black neighborhoods, we’re not really getting that far.”

The current iteration of UPLIFT is DHCD’s first draft. The agency will be taking public comment on it until Dec. 29, and on Dec. 19 DHCD will host a virtual listening session from 12:30 p.m. to 2 p.m.

In January, DHCD will release UPLIFT’s final program guide, host an information session and start accepting applications.

Megan Sayles is a Report For America corps member.

The post Governor Moore announces ‘UPLIFT’ to accelerate homeownership in historically redlined communities appeared first on AFRO American Newspapers.