by Dominique Lambright

February is US Black History Month. It’s also a month to raise awareness of the extremely inequitable treatment Black communities have faced in the US, and the amazing contributions Black individuals and communities have made to the wellness of all people, despite the ongoing disadvantages.

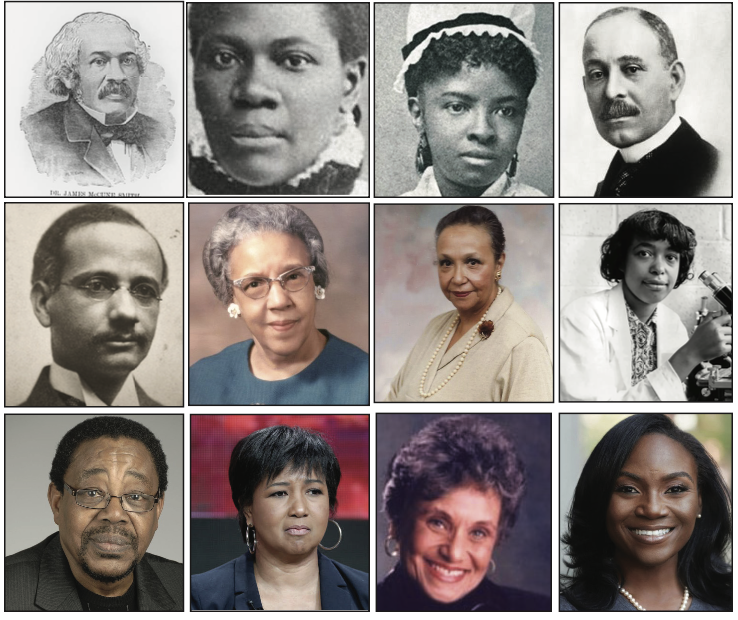

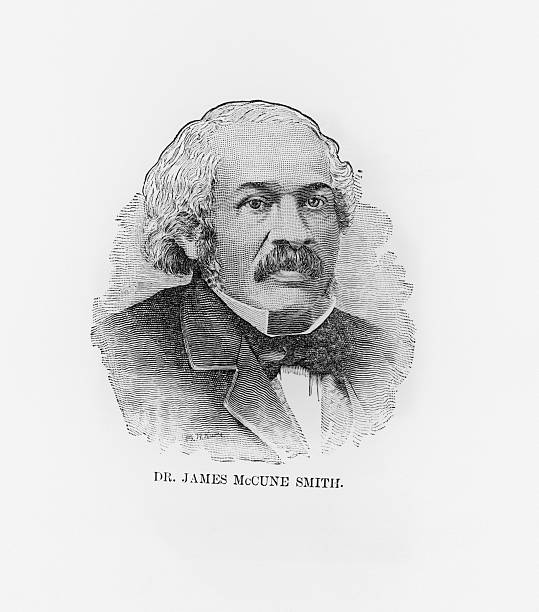

Dr. James McCune Smith (1813–1865)

The first Black American doctor was James McCune Smith. His early coursework from the African Free School in New York showed that he was a gifted and hardworking student who championed education.

After graduating, James McCune Smith decided to study medicine. He received a bachelor, master’s, and medical doctorate from Glasgow University in Scotland. He pursued his career despite US medical institutions’ ban on Black students.

In 1837, he returned to New York to practice medicine. He was an abolitionist who helped establish the National Council of Colored People in Rochester, New York, in 1855 alongside Frederick Douglass.

He wrote several scientific and abolitionist publications, including ones that disproved racial ideas, such as Thomas Jefferson’s Notes on the State of Virginia, phrenology, and the 1840 US Census’s racial prejudice. According to historian Thomas M. Morgan, Smith “made the overthrow of slavery plausible and effective” in addition to practicing medicine.

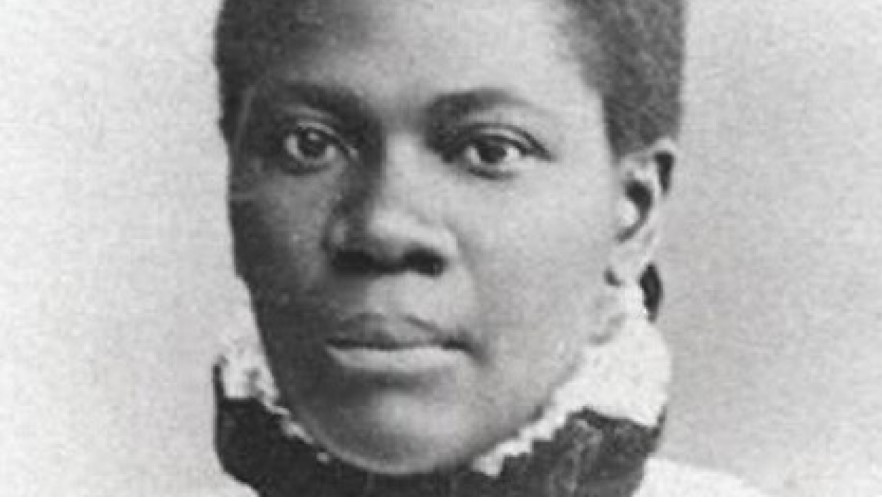

Dr. Rebecca Lee Crumpler (1831–1895)

The first Black American doctor was Rebecca Lee Crumpler. She was born in Delaware but reared in Pennsylvania by her aunt, who treated the ill using her ancestors’ wisdom.

Rebecca attended West-Newton English and Classical School in Massachusetts. She became a nurse in Charlestown, Massachusetts, after graduating. She bravely applied to the New England Female Medical College in 1860, 10 years after its founding, since she loved helping the sick. Rebecca was admitted, but she had to challenge two powerful societal beliefs: First, women lacked the physical and emotional stamina to perform medicine. Second, Blacks were dumb.

Since the New England Female Medical College closed in 1873, Dr. Crumpler was the sole Black graduate in 1864. Dr. Crumpler was one of 300 women doctors registered in 1860 and the only Black woman physician in the US for years.

After the Civil War ended in 1865, Dr. Crumpler served as a doctor under General Orlando Brown, the Assistant Commissioner of the Freedman’s Bureau, treating over 30,000 freed slaves, most of whom were women and children, despite her colleagues’ prejudice and misogyny.

Dr. Rebecca Lee Crumpler produced A Book of Medical Discourses in 1883 to treat, prevent, and cure various illnesses in newborns, children, and women. Doctors of all races utilized the first Black medical treatise for years.

Mary Eliza Mahoney (1845–1926)

The first American Black nurse was Mary Eliza Mahoney. Mary Eliza Mahoney was the first Black woman to get her nursing license in 1879 after graduating from nursing school at the New England Hospital for Women and Children.

Mary Eliza Mahoney was born in Dorchester, Boston. Her enslaved parents, who migrated to Boston from North Carolina, taught her the necessity of racial equality. Before attending nursing school, Mary worked at the New England Hospital for Women and Children. She was a janitor, cook, and nurse’s helper at New England Hospital.

Mahoney was accepted into the intense program at the professional graduate school for nurses in 1878 at age 33. Four of 42 women who joined the program that year completed it, including Mary Eliza Mahoney. She received her nursing license in 1879. After that, Mahoney became one of the first Black members of the Nurses Associated Alumnae of the US and Canada and the National Association of Colored Graduate Nurses.

In 1976 and 1993, Mahoney was honored in the Nursing and National Women’s Hall of Fame. She pioneered nursing and supported women’s suffrage. After the 19th Amendment’s passage on August 26, 1920, Mahoney was one of Boston’s first female voters.

Dr. Daniel Hale Williams (1856–1931)

Dr. Daniel Hale Williams built Provident Hospital, the first multiracial hospital. He pioneered open-heart surgery.

Sarah Price Williams and Daniel Hale Williams II had Daniel Hale Williams III in Hollidaysburg, Pennsylvania. When Daniel was ten, his father, a barber and Equal Rights League member, died. He returned to school after shoemaking and barbering. He apprenticed to surgeon Dr. Henry Palmer and attended the Chicago Medical College.

After graduating, he used Louis Pasteur and Joseph Lister’s latest sterilizing methods in his clinical practice. In 1891, he founded the Provident Hospital Training School for Nurses, the first hospital with a racially integrated nursing and intern program.

In 1893, Provident Hospital received a guy with a serious chest stab wound. Dr. Williams stitched together the man’s injured heart without blood transfusions or sophisticated surgery. He was one of the first doctors to conduct open-heart surgery, and the patient survived for years.

Williams became Freedman’s Hospital’s principal surgeon in 1894. He revitalized and expanded the hospital’s offerings. He worked as a surgeon, administrator, and instructor at many hospitals for over two decades, advocating for Black doctors. He co-founded the National Medical Association for Black doctors in 1895.

Dr. Solomon Carter Fuller (1872–1953)

Dr. Solomon Carter Fuller, the first Black American psychiatrist, trained directly under Alois Alzheimer and pioneered Alzheimer’s research and therapy.

Liberian-born Solomon Carter Fuller moved to the US aged 17. Solomon C. and Anna Ursilla Fuller, Liberian-Americans, were his parents. His grandfather, a former slave, acquired his and his wife’s freedom and helped establish a Liberian community of Black Americans.

Carter loved medicine. He discovered pathologies while doing an autopsy other doctors didn’t want to do. He attended Livingstone College in North Carolina, Long Island College Medical School, and Boston University School of Medicine. Like other Black doctors, Carter was discriminated against, underpaid, and overworked.

He studied post-graduation at Munich University to enhance his profession. Alois Alzheimer chose him to investigate pathology and neuropathology at the Royal Psychiatric Hospital at the University of Munich. He became a specialist in syphilis diagnosis and treatment and taught physicians. He advocated for Black war veterans he treated.

Dr. Carter released the first complete Alzheimer’s disease review and the ninth case. He taught in Boston and researched Alzheimer’s after returning to the US. He helped English-speaking doctors grasp the problem and early treatment.

Dr. Ruth Ella Moore (1903–1994)

The first Black Ph.D. in natural sciences, Dr. Ruth Ella Moore, helped comprehend infectious illnesses. Her parents were renowned artists, entrepreneurs, and seamstresses from Colombus, Ohio. Moore graduated from Ohio State University with a Bachelor of Science in 1926 and a Master’s in 1927 with her mother’s assistance. She received the first Black American Ph.D. in Bacteriology in 1933 after returning to her old university.

Her dissertation study examined TB, the second greatest cause of mortality in the US. Her work was crucial to finding a cure a decade later.

Dr. Hildrus Poindexter, another Black scholar, and scientist, recruited her after graduation to assist and rebuild Howard University’s clinical section. She headed the Bacteriology Department until 1960. Dr. Moore led Howard University’s first department as a woman. Dr. Moore’s work and lectures helped reduce infectious illnesses and encouraged other Black scientists.

Dr. Moore was a famous academic and a talented seamstress. Her outfits are in US garment museums.

Dr. Jane Cooke Wright (1919–2013)

Dr. Jane Cooke Wright was the first Black American woman to become medical school’s associate dean. She pioneered chronic illness research and cancer research.

Corrine and Louis Tompkins Wright had Jane Cooke Wright in 1919 in New York City. One of the first Black Harvard Medical School graduates, Louis Tompkins Wright, founded the Cancer Research Center at Harlem Hospital and was the first Black doctor to work at a New York City public hospital.

Dr. Jane Cooke Wright interned at Bellevue Hospital as an internal medicine assistant resident from 1945 to 1946 after graduating from

New York Medical College with honors.

After joining her father, the founder and head of the Cancer Research Foundation at Harlem Hospital, Dr. Wright became a visiting physician and staff physician at New York City Public Schools in 1949.

Dr. Wright and her father advanced anti-cancer chemical research, achieving multiple patient cancer remissions. Dr. Wright became Cancer Research Foundation director when her father died. Dr. Wright became an assistant professor of surgical research and cancer chemotherapy director at NYU Medical Center three years later at 36. President Lyndon B. Johnson nominated Dr. Wright to the Presidential Commission on Heart Disease, Cancer, and Stroke in 1964. The commission established chronic disease treatment clinics countrywide.

Dr. Wright pioneered numerous things. She wrote several publications and promoted cancer research internationally. Dr. Wright became the first Black associate dean at New York Medical College in 1967. She was the first female New York Cancer Society president in 1971.

Dr. Patricia E. Bath (1942–2019)

Dr. Patricia E. Bath was an ophthalmologist, inventor, and laser scientist noted for her work in blindness prevention, treatment, and cure. Her Laserphaco cataract surgery technology and method greatly influenced public health. She was the first Black American woman to patent a medical device.

Dr. Bath was inspired by Dr. Albert Schweitzer’s Congo leprosy work as a kid. She won science honors at 16. She interned at Harlem Hospital in 1969 and completed a Columbia University ophthalmology fellowship in 1970 after graduating from Howard University College of Medicine. She became the first ophthalmology resident at New York University.

Dr. Bath was instrumental in introducing ophthalmic surgical instruments to Harlem Hospital Eye Clinic. She convinced Columbia academics to operate on blind individuals for free. “My love of mankind and enthusiasm for helping others pushed me to become a doctor,” she said.

Dr. William G. Coleman Jr. (1942–2014)

Dr. William G. Coleman Jr. was the first permanent Black scientific head of the NIH Intramural Research Program (IRP). He led transdisciplinary research on biological and non-biological health inequalities and their effects on cancer, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and other chronic illnesses. He led NIH’s National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities.

Before joining the NIH, Dr. Coleman helped me understand Helicobacter pylori’s pathogenic processes and drug resistance. These bacteria may cause gastritis, ulcers, and cancer.

Dr. Yvonne Maddox, former NIH acting director, remarked, “Dr. Coleman’s contributions to research are

far-reaching. Bill Coleman’s efforts will assist many who have never met him, especially with infectious illnesses, which are difficult.

After his death, the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD) established the William G. Coleman Jr., Ph.D. Minority Health and Health Disparities Research Innovation Award to fund high-impact one-year research projects.

Dr. Mae C. Jemison (b. 1956)

Dr. Mae C. Jemison was the first African-American woman in space. She graduated from Cornell University Medical College in 1981 before becoming an astronaut. Dr. Jemison became interested in global health while studying in Cuba and Kenya and working in a refugee camp in Thailand. She taught and researched in Sierra Leone and Liberia as a Peace Corps medical officer following her internship at LA County and USC Medical Center.

Jemison Group, her consulting business, incorporates key social-cultural concerns with engineering and scientific initiatives like satellite technology for healthcare delivery. NASA’s training program was her career transition in 1985. She became NASA’s first African-American astronaut trainee in June 1987. She took a Dartmouth teaching scholarship after leaving NASA in 1993.

Dr. Marilyn Hughes Gaston (b. 1939)

Dr. Marilyn Hughes Gaston is a pediatrician who was the first Black woman to lead a Public Health Service Bureau and whose sickle cell disease research led to countrywide newborn screening programs.

Marilyn Hughes Gaston was born in Cincinnati, Ohio, in 1939 to medical secretary Dorothy Hughes and waiter Myron Hughes. Gaston’s family lived in public housing for much of her youth. At nine, she saw her mother faint in the living room and decided to become a doctor. Her uninsured mother had cervical cancer. From then on, she wanted to alter things.

Gaston attended a college preparation school when her family left public housing at age 12. Gaston wanted to pursue medicine but battled racism, misogyny, and prejudice as a poor Black woman. Her parents encouraged her to pursue her aspirations despite hardships. Gaston idolized her godmother, who desegregated public venues.

Gaston studied zoology at the University of Miami in Ohio after medical and academic authorities discouraged her from pursuing pre-medicine after high school. After graduating in 1960, a hospital doctor urged her to study medicine. In 1964, she entered Cincinnati’s medical school. Six Black women graduated that year, including Dr. Gaston.

After admitting an infant with a significantly swollen hand and no injuries, Dr. Gaston became interested in Sickle Cell Disease (SCD) while interning at Philadelphia General Hospital. The supervising resident advised she check for SCD, and the infant was swollen from infection. From then on, she studied SCD and altered her life and how we screen and treat it in the US and worldwide.

Dr. Gaston received government money to examine SCD in youngsters. She produced a landmark 1986 research showing that long-term penicillin therapy prevents SCD infections. The research prepared SCD screening for prophylactic penicillin. 40 states had SCD screening programs by 1987, saving many lives.

Dr. Gaston was the first Black woman to lead the Health Resources and Services Administration Bureau of Primary Health Care in 1990. She managed a $5 billion budget and 12 million low-income patients.

Cincinnati and Lincoln Heights, Ohio, honored her with a day. She earned the 1999 National Medical Association scroll of distinction for public health work. A scholarship program at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine named after her awards full scholarships to economically disadvantaged minority students each year.

Dr. Kizzmekia Corbett (b. 1986)

Dr. Kizzimekia Corbett, Ph.D., is a National Institutes of Health (NIH) scientist leading Moderna COVID-19 vaccine development. She informed then-president Donald Trump about the coronavirus early in the outbreak.

Born in Hurdle Mills, North Carolina, Corbett grew up in Hillsborough. Her early professors pushed her mother to enroll her in higher studies.

Dr. Corbett received her BS in Biological Sciences and Sociology from the University of Maryland in 2008. Meyerhoff Scholar and NIH Undergraduate Scholar, she obtained her BS. In 2014, she received her Ph.D. in Microbiology and Immunology from UNC Chapel Hill.

She joined the NIH’s Vaccine Research Center (VRC) after graduating. She studied and developed dengue, respiratory syncytial, influenza, and coronavirus remedies for 15 years. She created a universal influenza vaccine in Phase I clinical trials in addition to the coronavirus vaccine.

Dr. Corbett’s work and advocacy are crucial in a world where Black children are less likely to study STEM.